Susana Torres Molina, with her own dramatic text and very successful direction, is currently presenting, at the Nün Teatro Bar in Buenos Aires, her work The Foundation. This production has many merits. With admirable simplicity and nakedness, Torres Molina’s text comes to life in excellent actors masterfully directed.

Molina is a prolific writer, director and theatrical researcher, an author of many plays, including Extraño Juguete, A Otra Cosa Mariposa, Espiral de Fuego, Amantissima, Canto de Sirenas, Paraíso Perdido, No sé tú, Nada Entre los Dientes, Cero, Derrame, El Manjar and other works. Many of her plays have premiered in New York, Washington, D.C., Rio de Janeiro, Madrid, London, Mexico, Montevideo and Caracas.

According to the description published in the press, La fundación is an institution that was linked to the Christian Family Movement during the 1970s in Argentina. It delivered babies for adoption to married couples who demonstrated a deep connection to the concepts and values of the Catholic religion and to the dictatorship, the self-named “Proceso de reorganización nacional” (National Reorganization Process, 1976–83). Postulant couples were subjected to a rigorous and thorough examination before being granted the right to such “adoptions.”

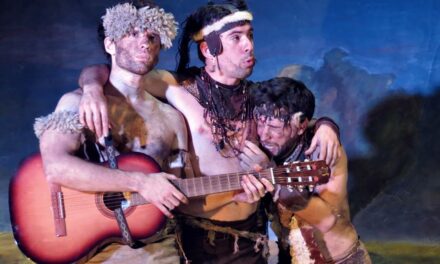

The set features a single table, four chairs and two empty bookcases that divide the space of the scene from the obscene and prevent the audience from seeing what lies behind the Foundation’s apparent correctness and elegance. The set, the performances, and the lighting cohere admirably, needing no other staging elements. The work, without mentioning the word “dictatorship” or showing violent or unpleasant scenes, strikes the viewer who understands that behind the Foundation’s facade exists a dark world in which newborns are taken from their mothers and given to the “right” couples. After the women give birth—in a very appropriate medical environment and with professional attention—in the detention centers of the dictatorship, their babies are taken and the mothers are disappeared. Torres Molina’s staging also shows the involvement of the priest from the Argentinean Catholic Church in the illegal and clandestine transaction of giving babies away.

In this play, the rhythms, the tones, the gestures and the bodies and attitudes of the actors help create the illusion that the spectator is viewing a masquerade of kindness and concern for others, as is expected of the known non-profit Foundations. A lawyer (Santiago Schefer), with a body and gestures evoking the military and a high-class elegance, a secretary (Estela Garelli), also politically correct, do not lose their smiles, their good manners or their composure until the moment it is clear that Marta (Florencia Naftulewicz) wants to know the origin of the baby they plan to give to her and her husband, Pedro (Emiliano Díaz). Pedro is the son of a military man and considers it an advantage to obtain a child who will be registered as his son. That baby will never appear to have been adopted.

In the current Argentine context, in which grandson number 122 has just appeared thanks to the actions of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, La Fundación must be read in the context of the post-dictatorial policy of the current government. The stage confronts and testifies to the memory of those years as a repudiation of the attempts of President Macri’s neoliberal government to erase that memory, either via the historical “negacionismo” or via many other actions coherent with this purpose. Susana Torres Molina’s play states visually and verbally that the past should not be forgotten. The stage reminds us of the most repugnant action of the dictatorship: to kill mothers after they’ve given birth to their babies in order to deliver them to those considered apt to raise healthy citizens, not poisoned by the ideology of political prisoners.

The spectator goes from witnessing something that seems innocent at first, a couple who come to “adopt” a child from the Foundation, to discovering the horror that meant the theft of babies in the detention centers during the “Proceso de reorganización nacional.” At the end of the play, it becomes clear that Marta is determined to discover the origins of the baby and the details of the negotiation. She has become suspicious after her close friend, Ines, is disappeared while she is pregnant. We, the spectators, arrive at the final surprise and an epiphany when we realize that these babies are given through adoption to “decent” “Christian” “good living” people, the military or their families, to save them from “evil.” That’s when the masks fall. When the light goes out, we realize that we have been in a place close to hell. We leave with tight throats and constricted hearts.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lola Proaño Gomez.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.