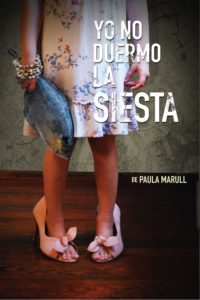

When Prince Charming shows up on a dilapidated motorcycle in the middle of the night, seemingly half-drunk, and later returns with a tray of empanadas instead of the glass slipper, what’s a woman to do? Such is the dilemma of Dorita, the hard-working, confident, self-sufficient protagonist of Yo no duermo la siesta who refuses to settle for less when it comes to men. Written and directed by Paula Marull, this enchanting award-winning comedy is now in its third season at the Espacio Callejón theater in Buenos Aires, and it continues to play to sold-out audiences each week.

Yo no duermo la siesta is set in a rural town during the dog days of summer, and it offers insightful perspectives on the day to day life in such locales with respect to social values, traditions, and idiosyncrasies, as well as the hopes, dreams, and concerns of the local residents. Although the play puts the spotlight on small-town life in Argentina, it also offers a fresh, innovative view on some of the broader, more universal themes that pertain to an urban audience as well. The dramatic action of Yo no duermo la siesta takes place in Hilda’s house, which is occupied by Hilda, her handicapped brother Anibal, her young daughter Rita, and Dorita, who is their live-in housekeeper. These characters together represent a working class family, as suggested by their modest home with limited furnishings that are generally in poor condition: a basic table and chairs, a kitchenette, an old sofa, Dorita’s twin bed off to the left, and a small bench off to the right where the characters sit outside to people-watch and drink mate. They also entertain themselves by observing the ants and a dead bird on the sidewalk, and these details, together with their mangy dog and the oppressive heat, are a constant metaphorical reminder of the stagnation that often typifies small town life.

Yo no duermo la siesta is a well-developed, romantic comedy that offers a unique blend of various literary genres and leitmotifs including realism, magic realism, children’s literature, and a coming-of-age story. Through a masterful weaving of elements from these various literary traditions, along with the intertextuality generated from stories and archetypal characters that are well known to her spectators, Marull has spun a wonderfully creative and entertaining tale. Intertextual literary allusions abound in this play, and they serve to add additional layers with respect to thematic and character development due to the familiar archetypes and plots that they evoke.

Without a doubt, one of the consistent literary influences in Yo no duermo la siesta is the story of Cinderella, whose iconic characters, situations, and conflicts are found throughout Marull’s play. The intertextual relationship between these two works is suggested right from the beginning given Dorita’s situation as Hilda’s housekeeper, for she is always home cooking, cleaning, washing clothes, and taking care of Anibal and Rita. The demanding, strict nature of Hilda with respect to Dorita further suggests that the protagonist represents a Cinderella-like character, as Hilda’s behavior often brings to mind the cruel step-mother in the children’s tale.

Following the Cinderella story line, the figure of the prince in Yo no duermo la siesta is found in the nameless young man who is simply referred to as Hijo de Cacho (Cacho’s Son). Curiously, this character is more of a distortion of the noble, romantic archetype, given that he is a rustic, blue-collar worker who has a bit of a rebellious nature. Unlike the fairy tale prince, Hijo de Cacho is presented as a derelict type of guy, with long hair and dirty pants, who races around town on an old motorcycle. Furthermore, he is not at all skilled when it comes to courting women. It turns out that he is Dorita’s ex-boyfriend, and he stops by the house occasionally in the hopes of rekindling their relationship.

No version of the Cinderella tale would be complete without the presence of a fairy godmother. In Yo no duermo la siesta this magical figure is embodied by Natalí, Rita’s friend from the neighborhood who spends the day at her house because her mother is gravely ill. Natalí initially appears on stage dressed in a princess outfit that includes a pretty dress, costume jewelry, a “magic wand”, and high heels that are much too big on her. Although this attire at first appears to be that of a little girl playing dress up, later, when Natalí begins to instruct Hijo de Cacho in the art of love, it becomes increasingly more apparent that she is, in fact, a true fairy godmother in this play. Not only does she advise Hijo de Cacho on how to conquer Dorita, but also, through a few strokes of her magic wand, she actually orchestrates the amorous encounter between the protagonist couple complete with a passionate kiss, romantic music, swirling confetti, and wind blowing through their hair. Surely this enchanting, very theatrical scene will not soon be forgotten by the audience. Although Hijo de Cacho does not have the fairy tale castle, nor a white horse such as the one pictured on the wall in Dorita’s room, he does clean up well, seems willing to modify his ways, and, in the end, promises Dorita a happy life together.

Natalí’s role in Yo no duermo la siesta is pivotal not only as the fairy godmother figure, but also as the protagonist of the parallel story that develops due to her mother’s fatal illness. The fact that Natalí must face the impending death of her mother clearly puts her at the center of a bildungsroman, as this painful loss will mark the end of her childhood; that is, the end of her innocence and carefree life as the rambunctious little girl who engages Rita in all kinds of games and mischievous acts. Through their capricious antics throughout the play, Marull effectively recreates the playful, fantasy world of children, and this contrasts sharply with the tragedy that awaits Natalí at home, where life will never be the same. The fact that she is about to traverse the threshold to adulthood is also suggested frequently as she repeatedly asks each character to help her “cross”. While this request, which everyone refuses in an effort to protect her, is made in the context of asking someone to accompany her home, the vagueness of the request (“cross” what?) allows for the symbolic interpretation in the sense of growing up. Additionally, at the end Rita explains to Natali how to get back home, helps her don one of Hilda’s fancy dresses, and convinces her to go by herself with the assurance that Rita will be with her in spirit. Clearly the maturation path that Natalí is about to follow must be taken alone, and nobody can truly shield her from the pain and sorrow that awaits her at the end of the road.

Yo no duermo la siesta is marked by an ongoing break with the traditional values and customs that frame this play. While the defiant tone of the title is most directly associated with Natalí, who refuses to nap during siesta hour, it also foreshadows Marull’s debunking of traditional gender roles such as those exhibited in classic fairy tales. Dorita is presented as an independent young woman who makes her own decisions regarding relationships and her future. Likewise, Hijo de Cacho hardly resembles the traditional prince charming archetype, although through Natalí’s mentorship he does manage to win Dorita’s favor. Paula Marull has, in short, created a delightful, modern, hybrid fairy tale peppered with the magic that one still expects of this genre. The play is staged with an excellent cast that includes Marull’s twin sister María Marull, who gives a wonderful, heartwarming performance in her role as Dorita. Additionally, Marcelo Pozzi’s impressive interpretation of the disabled Anibal is both captivating and quite convincing. The catalyst role of Hijo de Cacho was adeptly played first by William Prociuk, who this year was substituted by Juan Grandinetti. The talented Grandinetti family is further represented in this comedy by Sandra Grandinetti as Hilda, and Laura Grandinetti as Rita. Finally, Micaela Vilanova continues to charm audiences in her role as Natalí, the romantic, naughty little girl who simply wants to be with her mother, enjoy her fantasies, and make dreams come true.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Susan Berardini.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.