There are mutual squeals of delight when Belgian dance artist, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Spanish flamenco dancer, Maria Pages are reunited after “far too long” at a Tokyo rehearsal studio.

Pages, 54, has flown in from Madrid to promote the pair’s 2009 work Dunas (Dunes), which sees its Japan premiere this month at the Orchard Hall in Shibuya Ward—just down the road from the studio we are all sitting in.

Cherkaoui, 42, is in Tokyo to direct an all-Japanese cast in a run of his play Pluto, based on the Naoki Urasawa manga of the same name—though by the look of him, he’s happy to join the interview just so he can spend more time with his friend and collaborator.

“I’d watched Maria’s videos, such as Firedance (her 1995 piece for Riverdance) that she performed with the Irish dancer Michael Flatley, and I’d always admired her,” Cherkaoui says. “When we first met in 2004, I involuntarily said, ‘I’ve been a big fan of you for a long time.’ Then we became friends—she met my mother!—and we talked about life and, of course, dance.”

Pages adds: “One time, when we met in Mexico in 2006, we had lunch together and talked about collaborating. We weren’t sure how to do it, whether just I would dance, or both of us would.”

“In those days,” Cherkaoui chimes in, “I was trying to develop an aspect of my contemporary dance that drew on flamenco, especially how Maria does it.

She is extremely articulate, and what she does with her arms and body, it’s almost like sculptures.

“So then we slowly started working together on what has become Dunas. However, she is also a great choreographer, and she always had a bigger picture when we were creating something. I could see how she put pieces of puzzles together to make a final work.”

Pages says she has long been impressed by Cherkaoui—going back to his choreography for Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo in 2002—because he understands the power of using live music in his work instead of relying on audio that dancers will have to synchronize their movements to. Flamenco is primarily performed with live guitar, percussion, castanets, finger-clicking, and shouts of encouragement, so his approach makes the experience feel more authentic to her.

The music in Dunas, which fuses flamenco, classical, and Moorish elements—and creates a particularly powerful impact when paired with the lights—was created by Pages’ regular guitarist, Ruben Lebaniegos, and Szymon Brzoska, a frequent Cherkaoui collaborator since his Shaolin monk piece, Sutra in 2008.

Still, the main draw here is the dancing, and Pages says that when it came to choreographing Dunas, she and Cherkaoui realized they had a lot in common.

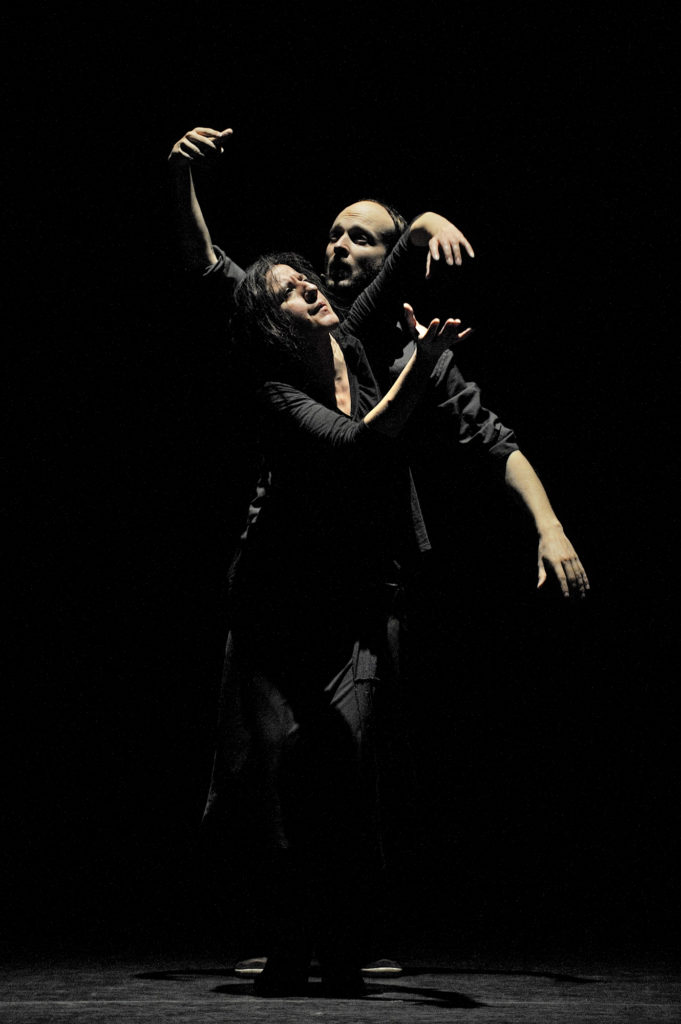

In sync: Spanish flamenco dancer Maria Pages (front) and Belgian dance artist Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui collaborated to create Dunas, which draws on flamenco and contemporary dance elements. | Photo: David Ruano

“At first the dance forms seem so different, but we realized their basis was similar,” says Pages, explaining that the pair shared many of the same problems—and approaches to solving them. “It was a very peaceful process, and creating together was a rich experience.”

Cherkaoui says if he goes back through his father’s Moorish (Moroccan) heritage and his mother’s roots in Belgium, which was part of the Spanish Netherlands from 1556-1714, he does share some culture with Pages. Yet he says he still found flamenco a challenge, “like a language that’s different from what I grew up with.

“It was a very intellectual process because there’s a lot of information in the movements,” he says. “Also, I didn’t get how and why the dancers and live musicians communicated, so I had to work all that out.

“Even now, though I’ve been dancing Dunas for years, my brain is sometimes on fire as it’s processing all sorts of information. But it’s an incredible experience for me and I learn something new from Maria and the team every time.”

As its title suggests, Dunas transforms as it moves along—much like the way the shape of a sand dune is transformed by the wind.

At the start of the performance, Pages and Cherkaoui are dressed in gossamer-thin sand-colored wraps. They then step up to each other and make contact. Cherkaoui copies Pages’ flamenco movements before gradually shifting into the contemporary style he is better known for. The effect of this smoothly flowing fluidity, in which veils are used to wonderful effect, is to make the viewer feel they are witness to the birth of a new form of cross-genre collaboration.

One scene that is particularly visually striking has Cherkaoui drawing a picture in sand that is projected on a screen behind Pages. She moves with the drawings until finally, she appears to merge with the image, becoming a tree. Then, as Dunas draws to a close the pair are wrapped in a veil in an intimate pas de deux.

“Of course I can’t dance in the way Maria does, but I can still have a relationship with her through my dance because we respect each other’s limits,” Cherkaoui says. “Things I can’t do, Maria will do, and finally those different elements become one piece.”

He points out that his collaborator’s flamenco is “very strong and powerful,” while his own style of dance centers on fragility. Those two elements coexist harmoniously in Dunas, and the two dancers eventually appear to become one.

“Ultimately, I am trying to dance like Maria, not like a forceful guy, and I’m interested in finding connections with her,” Cherkaoui says. “So it’s not anymore about flamenco; Dunas is about Maria. It’s not a competition between traditions of flamenco and contemporary dance—it’s a complement between two people.”

This post originally appeared on The Japan Times on March 20, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.