Bahrain’s Al-Sawari International Theatre Festival took place September 1-9 in Manama, concluding with I Will Die In Exile, an honorary play from Palestine

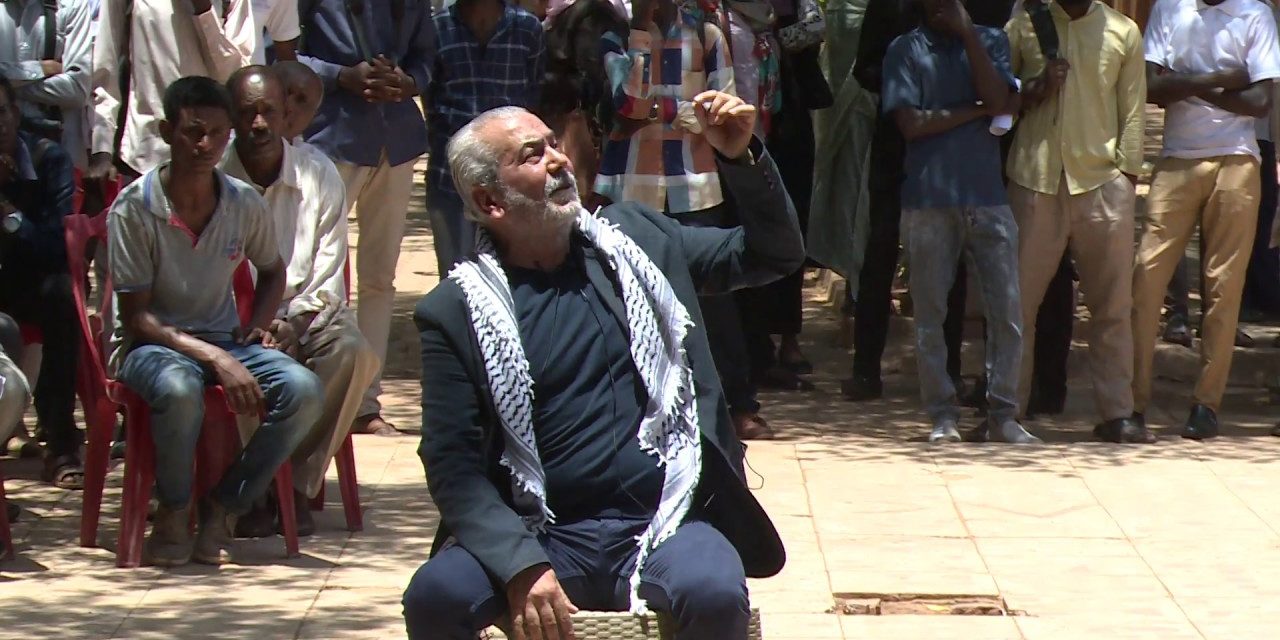

Bahrain’s 12th Al-Sawari International Theatre Festival concluded its performances with I Will Die In Exile by the Palestinian theatre maker and storyteller Ghannam Ghannam. The performance is a striking revival of the Arabic storytelling tradition in which the solo performer transforms the stage into an archive of collective memory.

At Al-Muharrak Youth Centre in Manama, the spectators sat in a rectangular formation. Traditional theatrical conventions were not observed. There was no darkness followed by theatrical lights. There was no separation between the spectators and the solo performer.

Ghannam moved between the center of the rectangular space and the entrance. He greeted some spectators and spoke to them with hospitality as if he was inviting them into his home, his life. There was no special arrangement in terms of scenography nor was there any special indication that the performance had now begun. The borders between reality and performance were blurred, just as the distinction between the artistic and the personal was blurred.

Gradually we understand we are witnessing a situation in which we are recognized as fellow humans, with the performance being an act of human solidarity and bonding. Ghannam has gathered us as if we were potential future friends and he has literally invited us to share his life story, the archive of his family history.

Ghannam talks to us directly. He walks from greeting the spectators into the performance just as simple as one walks from the living room to the kitchen.

I am astonished by that man who runs the programs of the famous Arab Theatre Organism in Sharjah and his ability to transform himself suddenly into an actor with his own style as if you have never known him.

Ghannam talks to us directly and looks in our eyes. He explains the nature of his performance and invites us to be relaxed and spontaneous. He creates the right environment for his piece where the introduction is already part of the game, and where we as spectators warm up by practicing our new presence as witnesses and allies in Ghannam’s open-hearted experiment.

I Will Die In Exile by Ghannam Ghannam. Photo: Al-Sawari, International Theatre Festival.

Ghannam does not use any tricks or theatrical devices. His only prop is a seat he borrows from the spectators’ area. He relies on his solid craft as a storyteller and theatre-maker, as well as on his belief in community and empathy.

For almost an hour, Ghannam takes us on a journey of personal memory where he reconstructs his life story in the form of a solo performance. Whether you call it a monologue, a monodrama, a one-man show or a storytelling session, what Ghannam does is totally personal and political.

This is not a performative act that could have been delivered by any other actor, nor is it a piece that could have been formulated differently.

I Will Die In Exile is made to be presented by its creator, intended to be performed as an autographical piece where everything is factual and there is no space for illusion or fiction. The piece is Ghannam’s register of his family history, and the authentic first-hand rendering and delivery of such a register is a prerequisite for the success of the experiment. What we are seeing is the actor’s life at the witness stand of the stage.

Ghannam tracks back his whole life from childhood, he traces the different stages of his life as if tracing different geographies of Palestine. The geographies of Palestine transform as he grows, while at the same time history changes what Palestine is. His growth is a register of political events, of conflict and of displacement.

Ghannam employs his personal memory as an archive of political conflict, identity manipulation, and dispersion. His story gradually becomes the story of the whole Palestinian community or even the whole Arab region.

We watch him carrying his pain, articulating it, screaming it, and transforming it into art. The story is passed onto the spectators, and hence expanded and liberated. Ghannam moves cleverly from the personal to the political to the historical, giving history his own storyteller’s flesh and bone, and in so doing inviting the community of Arab spectators to reflect on their own stories and histories, on their personal memory as a foundation of a collective Arab register of pain, domination and diaspora. Ghannam reminds us of our personal identities and our responsibility for future generations when it comes to exploring identity politics and the continuity of socio-political narratives.

I Will Die In Exile expands Ghannam’s story so aptly it brings his family close enough to us to feel like our own parents and relatives. The father, in particular, will forever remain in our memory, as a figure of self-accomplishment, challenge, and political integrity. Indeed, one could argue that the whole piece is a tribute to Ghannam’s father, the man who created a legacy of his own since the age of nine, supporting his son to protect his political principles against police torture even if the price was his life. The man who—apparently—put an end to his life by setting his body on fire in his own garden, after the death of his tortured son.

Ghannam’s piece is very painful, yet it is also cathartic and empowering. It seems that no healing is possible except by going through pain. This is also what happens to the community of spectators while witnessing this experiment.

In the performance, Ghannam buries his two brothers and his father, as if the performance is a funeral ritual. Yet he buries them in the most honorable way possible. His burial ritual is a performative one that retrieves history and political rights, revives the family figures, and celebrates them as icons of a collective Palestinian struggle where burial is never an end but merely the start of a new cycle of identity.

In the last scene Ghannam imagines his own death, he invents his own burial, transforms the seat into a grave stand, and acts out different potential scenarios of how his friends would honor his death. For a moment the scene seems sarcastic, then it becomes bleak and scary. It was an extraordinarily alarming scene to witness the actor’s prediction of his own death.

At the age of 64, Ghannam transforms himself into both a memory and a gravedigger. The situation of the live performer performing his own imagined future death is haunting. It is so strong it symbolically transforms the whole performance space into a graveyard. The performance space becomes a symbolic graveyard in which all those who died on the road of political struggle are buried. The spectators suddenly transform into mourners gathered around the grave of Ghannam, and I am personally shaken by the scene.

The performer ends his piece by indirectly telling us that it is only possible to retrieve our homelands in the graveyard where our birthplace is engraved and where our families can gather again from the diaspora and into one common land, the land of the graveyard. Ghannam almost says that we can only belong again in death. He also makes us feel the theatre can be that kind of graveyard where our identities are expressed, our collective memories stored, and our homelands reconstructed: Theatre as a victorious graveyard.

A version of this article appears in print in the September 28, 2018, edition of Al-Ahram Weekly under the headline: Graveyard Triumphs

This article was originally published on Ahram Online on October 3, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nora Amin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.