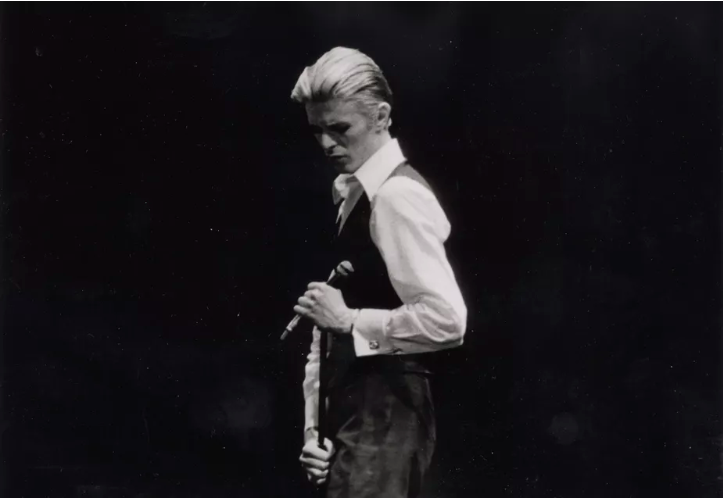

I’m not sure many saw David Bowie’s latest creative project coming. It was recently announced that he is involved as a writer (along with Irish playwright Enda Walsh) and composer in a new musical play, Lazarus, based on the film The Man Who Fell To Earth in which he starred in 1976.

A musical play, which is not what you expect after one of his characteristic periods out of the limelight. But if you look more carefully, such an involvement doesn’t seem strange at all–and we should expect great things.

The Man Who Fell To Earth is in turn based on a 1963 novel by Walter Tevis. Its hero, Thomas Jerome Newton, is a humanoid alien who comes to earth to obtain water for his dying planet. He starts a high-tech company to earn the billions that can enable his home world’s salvation. But politics, love, organized religion, (and alcohol) destroy his plans. The film is saturated in a post-Richard Nixon, Watergate, Vietnam sense of paranoia, covert observation and a world gone politically and ecologically off-the-rails. The appeal to our own era is all too obvious.

The film was a high point in the career of director Nicholas Roeg. This was Bowie’s first feature-film role, and an appropriately fragmented, ambiguous and strange viewing and sonic experience. In its wake, Bowie went on to make some of his greatest albums, most notably 1977’s Low.

Bowie’s performance as Newton was a spectacular success. New to acting in film, he plays someone acting in a new world. Newton’s survival on earth, Tevis’s novel, and the film make clear, is dependent on his successful imitation of acting in films that have, via television, reached his drought-stricken, dying planet.

Biblical Connections

And now this story transitions to the stage. Rechristened Lazarus, it’s to be directed by the Belgian theatre director Ivo van Hove, who has made some of the most searing and creative world theatre of recent years. Why he, Bowie, and Walsh chose to go with the title of Lazarus is, for now, a mystery.

But it’s certain that like Spielberg’s E.T., the film’s science-fiction plot of a wise but innocent visitor from above has more than a little to do with the New Testament story. The novel explicitly allies Newton with Christ and it’s very hard not to see some cruel parallels with the story of the Crucifixion in the last acts of the 1976 film. The production was, appropriately, announced on April 2, 2015–Holy Thursday in the Christian calendar.

In St. John’s Gospel, Christ seeks to resurrect his beloved friend Lazarus. In Bowie’s film, Newton similarly hopes to use Earth’s plentiful water to resurrect his own dying world. But Newton’s mission fails and Christ’s was, famously, successful, albeit in the short term.

The Raising Of Lazarus, Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1310–11.

If acting is at the heart of Bowie’s film, then the writing of Lazarus’s return from the dead in the Bible is also highly theatrical. Lazarus is initially buried in a cave behind a stone, which is rolled away. “Groaning in himself,” praying with “lifted” eyes, Christ accomplishes his spectacular miracle. The gospel’s “stage directions” of Lazarus appearance could not be more explicit:

And he that was dead came forth, bound hand and foot with graveclothes: and his face was bound about with a napkin.

This new play’s title is, then, as theatrical and tragic as it is imbued with the miraculous.

Angels in America

Although Lazarus will be the first direct collaboration between van Hove and David Bowie, it will not be their first artistic encounter. One of van Hove’s greatest achievements is his company Toneelgroep Amsterdam‘s production of Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer-prize winning plays, Angels In America.

Written in the early 1990s and concentrating on the early years of the AIDS crisis in New York, Kushner’s plays are a theatrical and emotional tour-de-force. They, too, are saturated in the Bible. “Do you know the story of Lazarus?” Louis, one of the central characters, asks at a crucial erotic moment. The scripts of the plays are full of music–not that of David Bowie–but when van Hove first saw the plays in the early 1990s, he felt they were calling out to be vitalized by Bowie’s songs.

And 16 years later this became reality. Toneelgroep Amsterdam premiered this production of Angels In America in 2008, performed by actors with stellar levels of energy, intelligence, and commitment. In 2014, the company took the show to Bowie’s adopted home city of New York.

Van Hove’s Angels In America. Jan Versweyveld

“When I do a play,” van Hove has said, “I want to do it in the most extreme way possible.” In this case, the extremity lay in his decision to ensure that every note of music in his production (along with almost every recorded sound) was taken from David Bowie’s work. This was an unprecedented move in the production history of Angels. As the text’s shocking twists and tragic momentum are embodied in the production, David Bowie becomes almost another character (and certainly an animating presence). His songs–The Man Who Sold The World, Life On Mars, Heroes, and many others–shimmer through the performance.

The complex pyrotechnics of Kushner’s stage directions (which include an angel crashing through a character’s bedroom ceiling) are pared back and much of their work is accomplished by searing white light and by having actors play, on onstage record-decks, David Bowie records.

So the musical Lazarus hardly comes out of the blue. Bowie and van Hove’s histories are steeped in stage and scripture.

Van Hove recently appeared on Dutch TV claiming that Bowie has already written several new songs for Lazarus. It remains to be seen whether these will find their way onto a new album. But it was Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s brave use of his music to reanimate plays that drew on the story of Lazarus that has enabled this startling collaboration–one from which new music by Bowie will certainly come forth.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on April 10, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Denis Flannery.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.