Meet The team behind Maklena and become part of the story!

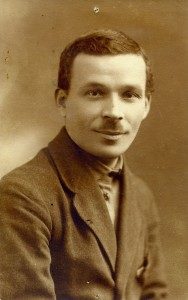

Mykola Kulish

Armed secret police were everywhere during the dress rehearsal for Maklena Grasa–in the dressing rooms with the actors, in the wings, and members of the notorious Cheka were crammed into every seat of the theatre. Written by Mykola Kulish in 1933, Maklena Grasa was seen as a deviation of Soviet Ukrainian culture by the Soviet authorities. It was performed five times before being banned. Shortly afterwards, Kulish was sent to a Labor camp and, in 1937, he was shot. Maklena Grasa has been brought to life once more for English audiences to appreciate and enjoy in a new translation, Maklena, by Maria Montague. After a number of successful runs, including the 2017 Edinburgh fringe, the Night Train Theatre Company wants to bring Maklena to more audiences across the UK and USA.

The event opened with historical and cultural insights from Dr. Rory Finnin, Head of Slavonic Studies at Cambridge University. From the 1920s onwards was a “manic time” in Ukrainian cultural life. Kulish was at the forefront of literary collectives and flourished amongst visual artists interested in expressing rural imagery within the modernist oeuvre. He joined the Free Academy of Proletarian Literature in 1924 and shortly afterwards, was elected to be its president. Whilst he was energized by the emerging dynamics of Soviet and Ukrainian identities in culture, the Kremlin wanted to see a metamorphosis in which Ukrainian identity would vanish as Soviet identity took root and emerged.

The characters in Maklena project some of the experiences of Kulish himself. He lost his mother in early childhood. Although poor, his intelligence was recognized by the local community, which supported him through his early schooling. As an undergraduate, he was drafted into the Russian Imperial Army. After WWI he returned to Ukraine and fought with a Bolshevik militia against the White Russians. He joined the communist party. In 1922 he was employed by Commissariat of Education in Odessa and became a playwright.

The scenes played by members of the Night Train Theatre Company hint at how the central characters risk losing sight of reality in surrendering to their obsessions. Maklena, a thirteen-year-old girl, dreams about the Soviet Union, while Zbrozhek’s an aspiring capitalist. He owns the house that Maklena and her family rent from him. He wants to buy the local factory. In one scene between Zbrozhek and his wife, he discovers that his ambition is thwarted by a Bank crash–his money’s gone. The question’s raised–can a man make a profit from his own death? He realizes that he has life insurance–if he’s killed the family can buy the factory and maybe he’ll live on. He decides too, that Maklena’s family will be evicted.

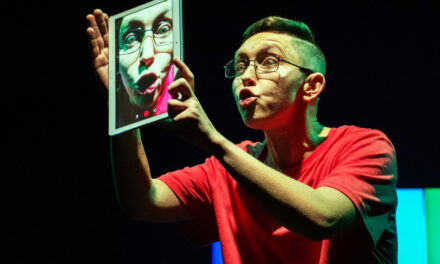

Maklena performance at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival © The Night Train Company and their Partners

In other scenes, Maklena discovers Padur, a musician living in the kennel alongside her dog. Maklena speaks of her desire to be involved in the revolution. Her family is starving but Maklena dreams of magical geese flying her away to the Soviet Union. Padur used to believe but now has long ceased to hope, although Maklena tempts him to believe once more. Padur provides the skeptical foil to the fixations of both central characters and warns about taking ideologies to extremes.

The physical drama was engaging too–under the direction of Lana Biba, London Physical Theatre School. In the scene where Maklena discovers Padur living in the kennel, the puppetry of a shawl’s skillfully employed to represent the character and movement of the dog. Scenes were interspersed with excerpts of the original music composed by Oliver Vibrans, waving Ukrainian folk musical motifs into an evocative and atmospheric score.

This article originally appeared in Ceel on May 25, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alison Miller.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.