This is the second in a two-part series by Barbara Hatley. Read Part 1 here.

Reflections on contemporary Indonesia and Australia-Indonesia relations at the AsiaTOPA festival

Of all the images of Indonesia and representations of Australia-Indonesia relations in AsiaTOPA performances, the topic of Indonesian fishermen and refugee boats arriving in northern Australia was a recurring theme.

Jaman Belulang (The Age Of Bones) by Australian playwright Sandra Thibodeaux tells the story of Ikan, a fifteen-year-old boy from a poor fishing village on the eastern island of Roti and working on a refugee boat, who is shipwrecked, picked up by the Australian authorities and imprisoned in Darwin.

One scene in Cahaya Memintas Malam (The Light Within A Night), a play devised and performed by students from University Pendidikan Indonesia (UPI) in Bandung and Melbourne’s Latrobe University, depicts two Indonesian fishermen detained for fishing illegally in Australian waters. Arguing back to the Australian official interrogating them, they ask what gives Australians the right to claim these waters, which were being fished by Indonesians long before their ancestors arrived, and by Aboriginal people for thousands of years before that.

In Cerita Anak (Child’s Story), a magical, participatory boat journey through the sea for young children devised by Polyglot Theatre and the Indonesian puppet theatre group Papermoon, a young boy tells of his terrifying voyage to Australia as a refugee. You can hear the boy’s fear and anxiety, and concern about their reception as the boat approaches land. This changes to great joy and relief with the news that a warm welcome awaits, and passengers/audience members step across a bridge to the shore.

Trouble “down under”

Based in Darwin, Sandra Thibodeaux knew first-hand of cases of young boys from Indonesia imprisoned in Australia for working on refugee boats. During her research for the play, she also visited Roti and saw the conditions they came from and heard about families who, like the mother and father in the play, had a son who had “disappeared.” With a teenage son of her own, Sandra felt their grief and bewilderment particularly poignantly. Through this play she wanted to convey such experience to Australian audiences, to present the other side of the story in contrast to the usual focus on the sufferings of Australians overseas. Sandra had met the highly respected Indonesian playwright Iswadi Pratama and knew his work with his group Teater Satu in Lampung. She invited Iswadi to co-direct the play with a cast made up of Teater Satu members and several Australian actors. Imas Sobariah, Iswadi’s wife and co-founder and leader of Teater Satu, played the parts of Ikan’s mother and an Australian official. Imas was impressed by Sandra’s plays, with their real-life themes, and was keen to be involved in this production since it addresses issues that people needed to know more about. The play was developed first in Indonesia and performed in Lampung, Bandung, and Tasikmalaya, then brought to Australia with a reduced cast and staged in Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney, and Darwin.

The play opens and closes on an island, its image projected on a screen also depicting the sail of a boat, in Ikan’s fishing village in Roti. After a short introduction from an old man, the narrator, we see Ikan and his parents at home, a still-sleeping Ikan teased by his father and ordered out of bed by his mother, who tells him as he goes off fishing in his tiny boat not to come home without a good catch. When Ikan fails to return his parents are distraught and call on the old man, a veteran sailor and ocean expert to help find him. At first unable to do so, the old man is helped out by a dalang, the puppeteer/narrator figure emerging from behind the screen. Ikan’s story is then played out through a mixture of filmic imagery, shadow puppetry, and interaction among live actors – his journey across the ocean on the refugee boat, wrecked on Ashmore reef, his capture and interrogation by Australian officials, his imprisonment and trial, and his eventual release and return home through the intervention of a sympathetic female lawyer.

Ikan is captured by Australian officials. His story is told through a colorful mixture of imagery, shadow puppetry, and live actor interaction. Photo: Barbara Hatley

The scenes of incarceration and trial are fantasied as occurring at the bottom of the sea, as they well might have felt, the old man observes, for a young boy locked away alone in an alien world “down under.” The Australian officials appear as awkward, lumbering figures in dive suits who use antiquated methods to assess him as not underage, thus legally detained, and ascend again to the sea surface; Ikan’s cell-mate is a rough but warm-hearted hammerhead shark, source of much Aussie-style humour; his astute lawyer at times takes the form of a white-pointer shark; the judge is an octopus.

In a question and answer session after one of the performances, Sandra Thibodeaux explained the use of fantasy and humor in these scenes as a way of conveying the play’s message in a less harsh, less confrontational way than a realistic depiction of such events. Responses to the performance in Indonesia were very positive; audiences had enjoyed the fun of the show, they were able to think later about its serious content. Australian viewers I spoke to agreed on the appropriateness of this approach. One question raised at the discussion session concerned the old man narrator with his rambling narratives and talk of sailing to Darwin himself in the past. What was the reason for including such a figure in the play? Sandra explained this was because an old man she met in Roti had actually made such a voyage, and spoke very positively about his time in Australia. His experiences provided interesting and thought-provoking reflections on Australian-Indonesian interactions, then and now.

The sea: danger, wonder, and identity

A real-life encounter also helped inspire the Cerita Anak performance. A young participant in a children’s theatre workshop had spoken so movingly of his journey to Australia on a refugee boat that Sue Giles, director of Polyglot theatre, included his story in the show. Another true story of the sea highlighted in the performance is from the town of Lasem, on the north coast of Java, where, in 1945, local people sank all their ships in an act of defiance to the invading Japanese. Their thriving fishing industry and maritime identity was destroyed and is only now recovering. Sue and Ria held workshops with the children of Lasem as part of the Cerita Anak project. They encouraged the children, described as their “deep collaborators,” to make paper boats. They then observed how they used them and incorporated these elements into the show. Such activities, developing children’s interest in and love for the sea, also contributed to local efforts to rebuild a maritime culture. In the performance itself, young children delight in a wondrous imaginary experience of the sea, while their parents and other adult audience members take in and contemplate real, contextual issues.

At its essence, Cahaya Memintas Malam is a tale about encountering the “other.” Photo: Barbara Hatley

Interestingly, the sea as a site of natural beauty, danger, and complex human interaction was a theme evoked also in the two dance productions at AsiaTOPA. Performed by a group of young men from the remote Eastern Indonesian region of Jailolo, under the direction of renowned Indonesian choreographer Eko Supriyanto, the rhythmic movements of Cry Jailolo evoke the beauty of the region’s underwater world, now threatened with destruction from environmental degradation. The international success of the work has both drawn attention to this situation and fostered the skills and aspirations of the young performers. In Balabala, the movements of young women dancers from the same community reflect the multiple traditional social roles of women and assert new strength and determination.

Encountering the Other together

The interrogation of Indonesian fishermen in the play Cahaya Memintas Malam was one of diverse interactions devised by the student writer-actors on the broad theme of an encounter with the Other. The framing story, an Indonesian folk-tale performed by the Indonesian students, depicts a poor farmer attempting to fish outside his own village area. The man is accused of killing a woman found in the stream and is subsequently executed. When butterflies are drawn by the sweet scent of the innocent man’s body block out the sun, causing crops to fail, the villagers acknowledge that they had been wrong to blame and punish the man simply because he was an outsider.

Many other scenes, meanwhile, depict everyday Australian–Indonesian interactions, related to the participants’ own experiences. For example: Australian students about to depart for Indonesia discussing their knowledge of the country and expectations of what they might find there; Indonesians coming to Australia doing the same thing in reverse; a drunken Australian couple looking for accommodation in Indonesia; a monologue by an Australian student expressing guilt at the difference between her own financial situation and that of people she met in Indonesia; and Indonesian students hosting Australians for an Indonesian meal.

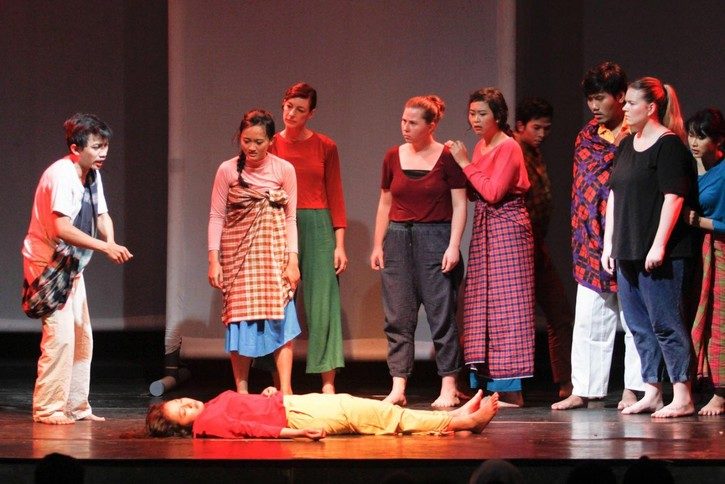

The scenes display a vibrant energy and playfulness, reflecting the enjoyment found in devising and performing them. The two groups had spent a month together in Indonesia, with the Australians, funded by the government’s New Colombo plan scholarships, studying Indonesian while working on the play, which was staged in Bandung, Jakarta, and Bali. Then the Indonesian group visited Melbourne for three weeks, assisted by La Trobe University, to perform at La Trobe and La Mama Theatre. The project drew on links between performers in Melbourne and Bandung which originated in student theatre activities at La Trobe in the mid-1990s. A few differences in approach were encountered, both groups noting a flexible, improvisatory Indonesian approach to the written script compared with a firmer Australian/Western stance. But with understanding and humor, these were overcome and all involved enjoyed and valued the collaboration; both Australian and Indonesian students expressed the wish to revisit one another’s countries very soon.

Many scenes depict everyday Australian-Indonesian interactions, such as a hosted meal. Photo: Barbara Hatley

Collaborations, connections, enlightening insights

Rich and varied collaborations and “creative conversations” clearly abounded in the Indonesia-related performances at AsiaTOPA. The range of contributors included internationally renowned artists, prestigious institutions and local community groups, professional actors and directors, student theatre groups, and in Cerita Anak, even Australian and Indonesian children. Audience participation occurred not only in Cerita Anak; during Art Is A Prayer, Tisna Sanjaya invited viewers to spray him with paint as he lay on a door, creating a series of outlines of a body entering a new space.

The staging of several of the plays in both Indonesia and Australia informed audiences in both countries about the issues portrayed and demonstrated new possibilities for “people to people” collaboration. Audiences in Australia had the opportunity to learn about a lesser-known aspect of Indonesia–its maritime regions and cultures–and to view Australia-Indonesia relations from the other side.

Next time

More could have been done, however, to extend the public impact of these activities and to benefit from the presence of the Indonesian artists in Australia.

Apart from the panel discussion with Garin Nugroho at Melbourne University and Eko Supriyanto’s participation in a discussion event at the arts space Dancehouse, no formal information sessions were held about the Indonesian performances and participating groups. The Q and A session about Jaman Belulang mentioned above was organized informally to take advantage of the brief presence in Melbourne of the playwright along with a Darwin-based academic and two lawyers experienced in refugee issues. Audience members at the performance at La Mama that night stayed on for the discussion, joined by some participants alerted through email networks, but numbers were necessarily limited.

A lively seminar about the play by Teater Satu performers held at Monash University that week, organized through the playwright’s personal connections attracted a very small audience due to late notice. With regard to the Australian–Indonesian student production Cahaya Memintas Malam, no public discussion session took place, in spite of the great potential interest of the play for Australian students, particularly those undertaking theatre or Indonesian/Asian Studies. I am not aware if any student groups attended performances or whether many secondary and tertiary students knew about the production.

Similarly, Melbourne audiences would not have been aware of the status of the founder/director of Teater Satu, acclaimed in a recent article in Inside Indonesia as “Indonesia’s foremost theatre director,” nor of the vital, innovative work of the Teater Satu group. While Tisna Sanjaya staged his performance art in the State Library forecourt, footage of his extraordinary environmental activism artworks in Bandung played inside the Library, but the screening was poorly executed. The information provided about them was very general, few people watched, and there was no chance for Tisna to talk about his work or meet with like-minded Australian artists or environmental activists during his stay.

These points are raised not to criticise the inaugural AsiaTOPA festival but hopefully to contribute to even greater success in the years to come. Spreading the word, building on these initiatives and making connections in the ways suggested above could be done by those in the wider arts and Indonesianist communities if alerted well ahead, and given the time to mobilize. Onwards and upwards, maju terus!

This post originally appeared on in Inside Indonesia on August 30, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Barbara Hatley.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.