This is the first in a two-part series by Barbara Hatley. Read Part 2 here.

Indonesian performances at the AsiaTOPA festival opened up ‘creative conversations’ between Australians and Indonesians.

Spanning more than two months, from late February to early April 2017, Melbourne’s inaugural AsiaTOPA (Asia–Pacific Triennial of Performing Arts), coordinated by the Melbourne Arts Centre, was a huge, diverse undertaking, involving many genres and venues and extensive collaboration with other institutions. In the view of festival organizers, this wide range of activities shared a particular focus. AsiaTOPA, was “not a survey,” wrote the directors in the program. It did not simply “showcase” Asian arts, but reflected “creative conversations” between Australia and its neighbors in the Asia–Pacific–”intercultural collaborations, commissions, production sharing, creative exchanges, residencies.” It was intended to “delight and enlighten while creating new opportunities and connections for Australian artists and audiences.”

Indonesia was well represented at AsiaTOPA. Satan Jawa, a black-and-white silent film by famed Indonesian director Garin Nugroho and accompanied by members of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and Javanese gamelan musicians, was a major highlight of the festival. The film and musical performance was watched by an audience of over 2000 at its single performance at Melbourne Arts Centre’s Hamer Hall. Also staged in the main Arts Centre were two dance productions by choreographer Eko Nugroho, Cry Jailolo and Balabala, involving young male and female dancers from eastern Indonesia. Cerita Anak (Child’s Story), a performance for children by Papermoon Puppet Theatre, was the result of another collaboration, this time with Melbourne’s Polyglot Theatre. The music duo Senyawa participated in a program of alternate music and dance performances, watched by big crowds of young people in a specially created space on the Hamer Hall stage. Two plays – both Australian–Indonesian productions – Jaman Belulang(The Age of Bones) and Cahaya Memintas Malam (The Light within the Night), were staged in the more intimate space of La Mama Theatre in Carlton. Tisna Sanjaya and other Bandung artists created a performance art event outside the State Library of Victoria, and video and installation art works by Dadang Christanto and Melati Suryodarmo were included in an exhibition entitled Political Acts. Two Indonesian women artists and one from Timor Leste participated in the Women of the World program of women’s performances and other activities at the Footscray Community Arts Centre.

How did the aims of the festival play out in relation to these Indonesian performances? What creative conversations and collaborations between Indonesia and Australia were involved? What new connections were made? What kind of “delight” in Indonesian artistic expression and enlightenment around Indonesian society and culture was conveyed?

This article takes up these questions, focusing first on Satan Jawa as the “big item” Indonesian event at AsiaTOPA, attracting the most public attention, and then in a second article to follow, will extend the gaze to other shows.

Satan Jawa: background and preparation

Two years ago filmmaker Garin Nugroho met with members of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and raised the prospect of working together creatively. The work Garin had in mind was a silent film accompanied by Western orchestral and gamelan music, inspired both by early black-and-white silent cinema and Javanese shadow puppet theatre, wayang kulit. The proposal accorded with emerging ties between the MSO and Indonesia, fostered by the Sultan of Yogyakarta, extending into a visit to Yogyakarta by the orchestra in 2016; the Melbourne Arts Centre commissioned the performance, with the Sidney Myer Fund supplying funding. Australian composer and conductor Iain Grandage and Javanese gamelan maestro Rahayu Supanggah commenced working together to create music for the show. So began, in Grandage’s words, a “deeply collaborative and highly enjoyable” process of composition, within a broader framework of collaboration between the filmmaker, Australian and Indonesian musicians and singers and organizing bodies. For the Melbourne performance, the Indonesian musicians used gamelan instruments borrowed from the University of Melbourne and members of the Melbourne Community Gamelan were invited to attend a special gamelan jam session, or klenengan, with the visitors. A panel discussion with Garin Nugroho at Melbourne University before the show helped spread the word, attract interest and prepare audience members for what was to come.

Satan Jawa on stage

On the night of the performance, excitement mounted as orchestra members and gamelan players assembled in front of the film screen and the director and actors took their seats at the front of the audience. A wondrous blend of gamelan and orchestral music heralded the start of the show.

The opening scene of the film, set in the early twentieth century, shows a young Javanese man, imprisoned by Dutch colonial authorities for stealing, subjected to torturous punishment; later his spirit returns as Satan Jawa, the title figure of the film, to take vengeance for these wrongs. Another young man, Setio, from a poor village, falls in love with a beautiful aristocratic girl. He picks up her hairpin, fallen accidentally in the street, and goes to her house to return it, kneeling, extending his hand to her in a gesture redolent with admiration, desire, and entreaty. But her mother seizes the pin, and after a moment of agonizing suspense, heightened by dramatic musical accompaniment, plunges it into his hand, in brutal, scornful rejection. Setio then visits a market full of weird, grotesque animal creatures, objects, and spirits, and there makes a pact with Satan Jawa which enables him to become rich and marry his aristocratic beloved, Asih.

Coins rain down from above; Setio is seen alighting from a carriage with Asih and entering a big Javanese house. Elsewhere two women, Asih’s mother, and grandmother, perform a beautiful dance grieving her loss. By the terms of the pact, the house constantly disintegrates and must be repaired and rebuilt. Terrifying manifestations of the supernatural appear and reappear: a figure with a monstrous animal face, white-faced children holding skull masks, plagues of spiders, and a huge turtle with retractable head and beak. Asih learns of Setio’s connection with the satan and attempts to appease the demon with offerings, rituals, and dance. But what the Satan wants is Asih herself. Filmic images, shots of a temple statue with a huge erection and ground reliefs of a penis and vulva, with Asih’s figure seen momentarily standing astride one of them, embody his desire. Setio is seen writhing on a bed, in illness or madness. Finally, after a wonderfully sensuous scene of prolonged unwinding of her seemingly endless waist sash, Asih and the satan make love. A figure seen speared through the face is presumably Setio, his wife taken by the devil, doomed by the legend to become a pillar in his own house.

The film concludes with more magical music from orchestra and gamelan; audience members applaud vigorously then rise to their feet in a standing ovation. Garin Nugroho, along with the female star of the film, Abigail Asmara, composers Supanggah and Iain Grandage, and the director and assistant director of the festival, come on stage. Garin expresses gratitude and delight at the enthusiastic reception of his work by the Melbourne public.

Impressions, reactions, critical responses

Responses to the performance were indeed glowing. Press reviews described it as “a standout … sumptuous black and white film” which was “bewitching…deeply unnerving, surreal and sensuous in equal parts.” Audience members spoke of being entranced by the simultaneous impact of stunningly imaginative visual imagery and thrilling music, the beautiful voice of the pesinden Javanese woman singer combined with orchestral accompaniment. Film buffs were delighted by Garin’s interpretation of the classic genre of black-and-white silent film.

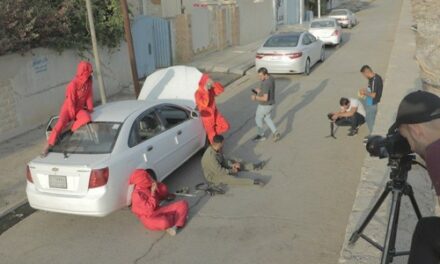

Critics hailed the performance as ‘sumptuous’ and ‘bewitching’. (Instagram @setanjawamovie)

Some viewers, however, expressed puzzlement over the meaning and significance of particular images and incidents, and the intent of the film as a whole. What was the reason for portraying Java/Indonesia in this way and how was it likely to be interpreted by the Australian public?

At the discussion session the night before, Garin had spoken of his films as presenting a “map” of Indonesian society and culture. He had come to understand that in every period of his career he has sought to make a statement about the conditions of that time. Among his Suharto-era films were Love On A Slice Of Bread which reflected economic affluence but lack of personal daring and initiative due to the repressive socio-political conditions of the time, and Surat Untuk Bidadari (Letter For An Angel), set on the island of Sumba, depicted Javanese domination of other regions of Indonesia. In the current period, many films are being made about religious heroes, all concentrating on Islamic figures. So he made a film about a leader of a minority religion, the Catholic bishop and nationalist figure at the time of the Indonesian Revolution, Suryo Pranoto. Amidst the black-and-white religious and political stereotyping taking place in Indonesia today, he wants to tell people they should “have the courage to be subversive”–tell true stories, not just approved ones.

Why Javanese mysticism?

So why Satan Jawa in 2017? What is the importance today of looking at Javanese mysticism in a historical frame?

Garin explained that the house shown in the film is that of his own grandfather, the site of reverent cultivation of traditional Javanese culture, where wayang performances and regular Javanese dance rehearsals were held. He and his eight brothers learned to dance there (in his case often reluctantly) and at night listened to frightening stories of haunting ghosts like Satan Jawa. Queried about the contradictions of this picture, the mixture of beauty and rich cultural resonance with threatening, dark elements, he replied that the important aspect of Javanese culture is this paradox itself. The ability to smile, then kill–to encompass such duality leads to a remarkable capacity to accommodate new forces–Hinduism, Islam, now computers and the digital age–and continue on.

Satan Jawa highlights the plurality of Indo-Javanese culture. (AsiaTOPA)

Renewed attention to the accommodating quality and plurality of Javanese culture is surely timely, in these days of increased religious and political intolerance within Indonesia and negative stereotyping of Islamic countries. But in what ways can such a message be seen embodied in the weird supernatural beings and erotic images of Satan Jawa? How is it conveyed to audiences, particularly those unfamiliar with Javanese/Indonesian culture? In a review titled Garin Nugroho’s Satan Jawa Flirts With The Dark Side, Nuraini Yuliastuti proposes an alternate interpretation. She sees in the demons of Satan Jawa reference to the use of mysticism by Indonesian politicians to gain power and position, the vengeful feelings of an aggrieved underclass, and the threat of a dark future, with a return of the repression of the Suharto years. A tempting reading, yet once again it is hard to see connections with specific images and events to enable one to find contemporary resonance in the film’s dream-like otherworldliness.

Other commentators see in the film an exoticised, fantasied portrayal of Javanese/Indonesian culture, a kind of cultural nostalgia. But is this necessarily a problem? Should Garin as director be free to present his own filmic vision, or does the context of a collaborative work with Australian artists for an Australian arts festival create different parameters? What if exotic beings and magical, supernatural forces in performance are elements which attract and interest festival organizers and which audience members find fascinating?

Such questioning of form and meaning, while complicating reception of Satan Jawa, arguably focused added attention on the performance, enhancing its public impact. Meanwhile, with regard to artistic achievement and creative intercultural collaboration, the production was deemed an outstanding success.

Collaborations, new and ongoing, also characterized other Indonesia-related performances at AsiaTOPA. Here, meanwhile, the contemporary social reference queried in relation to Satan Jawa was often a central aspect of the show. The second part of this review will examine the portrayal of Indonesia and of Australian-Indonesian relations in these performances, and how this was conveyed.

Barbara Hatley is Professor Emeritus in Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania.

This post originally appeared in Inside Indonesia on August 3, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Barbara Hatley.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.