Alkazi was not just the father of modern Indian theatre, but a pioneer who pushed the frontiers for all the arts.

In a tense moment in the play Tughlaq, the Arab historian Barani seeks to give the brilliant but beleaguered Sultan a piece of advice: “History is not made only in statecraft. Its lasting results are produced in the ranks of learned men”.

Spoken from the ramparts of Purana Qila in the national capital, with its lengthening shadows evoking a medieval setting, these lines from Tughlaq had a stunning resonance. Some years later, when Ebrahim Alkazi presented Girish Karnad’s opus again at Delhi’s Kamani Auditorium, its critique of the Emergency and the silencing of the intellectual class was unmistakable.

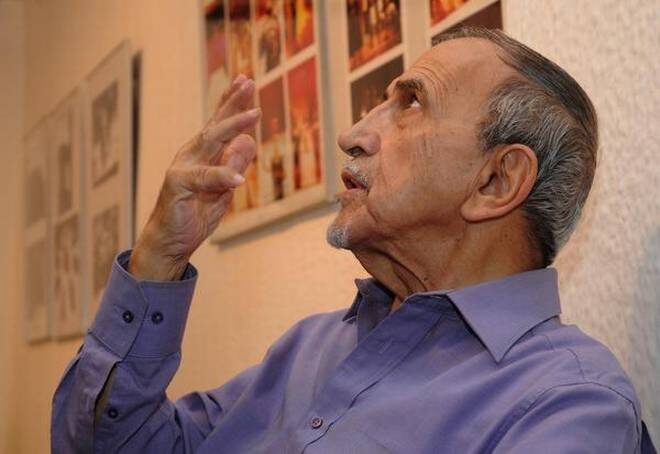

For over 50 years, Alkazi, who passed away last week at the age of 95, was in the vanguard of the arts, pushing tenaciously against the passivity of the Indian artist and audience alike. Karnad, whose Hayavadana and Tughlaq were landmark Alkazi productions, was to say: “If we were to choose an individual who formed the concept of Indian theatre, it would almost certainly be Ebrahim Alkazi.”

Famed as the director of the National School of Drama, he had initiated his practice in the cosmopolitan circles of Bombay in the mid-1940s. When much of Indian film and theatre talent had gravitated towards IPTA (the pre-Independence Indian People’s Theatre Association), Alkazi was drawn to the brilliant if the fleeting appearance of Sultan Padamsee on the Bombay theatre scene. He followed it up with a course at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, and a deep dive into post-war French, German and Russian theatre. Alkazi returned in 1951 to form Theatre Unit, a dynamic group where he bolstered entertainment with pedagogy and encouraged his audiences to assume the mantle of world theatre, as its rightful legatees.

Community engagement

For his Parsi, Christian, and Gujarati audiences, Alkazi held Hindi classes. He sought to take theatre to the local community that lived within a mile’s radius of his theatre as well as to the chattering mill audiences of several thousand workers. Among his close circle of enthusiasts were other theatre luminaries: Deryck Jefferies, Alyque Padamsee, and Sylvester da Cunha. Converting the rooftop of the building where he lived into an alfresco theatre, he launched into a vigorous programme, inviting audience comments even as he sought to locate theatre in the larger social fabric. As he said, “I think there is a very, very close connection between politics and theatre and between social conditions and theatre.”

Alkazi was also a keen artist and student of art: in England, he had spent hours studying major museum collections, and F.N. Souza was his flatmate. To introduce an understanding of modernism, he initiated 10 major exhibitions at Jehangir Art Gallery and narrated an apocryphal story. To demonstrate the art of Picasso, he thought of scouting around for the artist’s work among the city’s collectors and cognoscenti. To his own surprise, he found more than 40 pieces, including prints, tapestries, and ceramics, which he put into an exhibition.

Greening the desert

For the then-upcoming National School of Drama (NSD), Alkazi was invited to draw up a syllabus. He was not yet 30 and it would be another eight years before he accepted the position of director of the institution. When he came, he found Delhi a “cultural desert,” with none of the infrastructure required for a vivid art scene. His quest for an audience for NSD productions was the same: “The kind of audiences we were anxious to show our plays to were middle-class, the clerks, the office-goers, the small shopkeepers, the types of men you see walking in Paharganj and Daryaganj.” Energizing the Mandi House circuit, the NSD and its Repertory performed Lorca, Shakespeare, and Sophocles with the same energy and depth as Mohan Rakesh, Adya Rangacharya, or Dharamvir Bharti. The raging debates around indigenism in the arts were muted by the embrace of vernacular theatre. From the 60s on, the outstanding talent groomed by Alkazi at NSD was to directly feed an alternative stream of arthouse and then mainstream cinema and television.

After dedicating years to NSD, Alkazi crossed the Mandi House circle to Art Heritage, the gallery co-founded and run by his wife Roshan, which conducted a studied, well-regulated programme of exhibitions. The gallery would help disseminate his vision of Indian modernism even as he occasionally put up large, spectacular shows, such as those dedicated to Souza to resemble a church setting. Alkazi’s presence at his gallery was both sober and enlightening. He set rigorous standards for critical writing in his catalogs, and for decades, outstanding artists like Arpita Singh and K.G. Subramanyan continued to show with him.

In a late charge, when he was close to 70, Alkazi turned to a newfound passion for collecting photographs. At a time when the medium of photography was grossly neglected in Indian galleries and museums, he set up a gallery dedicated to photography in New York, and initiated, with the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, a vigorous programme of exhibiting and publishing colonial and 19th-century photography.

In his passing, Alkazi will be remembered for his singular exceptionalism, as one far ahead of his peers. In light of his achievements, the precarity of the present becomes acutely visible. One may, like Imam-ud-din in Tughlaq, well ask, “A kingdom needs not one but a line of rulers…Where are these guardians of your balanced future?”

The writer is an art critic and curator who runs www.criticalcollective.in.

This article was originally posted at thehindu.com on August 7, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Gayatri Sinha.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.