When he was 16, Hideto Iwai was perplexed as to why everyone around him unquestioningly jumped onto society’s student-to-salaryman conveyor belt. So, he broke free, dropping out of high school and picking up casual jobs where he could find them.

“But then I had problems at work because I couldn’t interact with people as cleverly as everyone else could,” he recalls.

That caused the Tokyo native to become a hikikomori, retreating into his room in the family home and withdrawing from society for four years before emerging in 1994 at the age of 20.

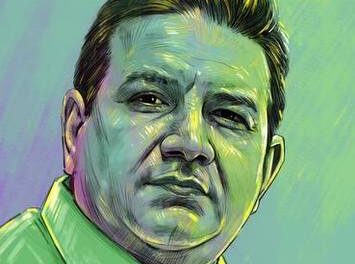

The now 44-year-old dramatist doesn’t fret over those lost years, though.

“Those experiences have worked positively in terms of my writing because I’ve been able to introduce many questions about our society into my plays,” he tells The Japan Times.

Iwai founded his own theater company, Hi-bye, in 2003 (“hai hai” is the term for babies crawling, and “bye” comes from the English sendoff). That same year, his new troupe made its debut with an autobiographical piece by Iwai titled Hikky Cancun Tornado. It has since been rerun several times and has spawned spin-offs in a so-called Hikky (Hikikomori Man) series, which has become a popular staple of Hi-bye’s repertoire.

Iwai has written on a variety of themes but still returns to his dysfunctional family for subject matter. Two such heartfelt (and surprisingly hilarious) dramas based on his past are Te (The Hand) and Fūfu (The Husband and Wife), and to celebrate Hi-bye’s 15th anniversary the playwright will present both pieces in different spaces at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre from August 18. The concurrent performances will let spectators see both shows on the same day if they’d like—a matinee and a soiree.

The Hand, which premiered in 2008, portrays a rare visit by two daughters and a younger son (Iwai’s position in his own family, played here by Kentaro Tamura) to their family home, where their parents, older brother, and grandmother all live together.

There, the father becomes increasingly belligerent as his children assail him with stories of how violent he was when they were growing up—behavior he insists he has no memory of. As the reunion increasingly turns into a shambles, the grandmother, who suffers from dementia, quietly passes away unnoticed.

“Before I wrote The Hand I’d tried in many ways to raise the entertainment factor by casting men to play women and using nonobjective props such as waist-high stands with doorknobs that the actors would symbolically have to turn in order to leave or enter rooms,” Iwai says. “However with this play I started writing about my own family instead—though I did have a man, Kazuyuki Asano, play the mother.”

Whereas people used to come up to him after a show to talk about the sets or the acting, Iwai says bringing his own experience into the story produced quite unexpected responses.

“Suddenly everyone wanted to talk about their own families and life stories—and that was when I realized what doing theater really means to me: It’s about sharing experiences and feelings.”

As a result, Iwai says he was increasingly encouraged to write his own feelings and experiences into a story—especially ones that evoked anger. This method is apparent in his 2016 drama The Husband And Wife, which premiered just months after the real events it covers occurred.

In this play, about Iwai’s parents, the story begins when his dictatorial father—an elite surgeon played by Iwai, who admits that even after acting the role he still doesn’t understand his dad—is diagnosed with lung cancer and has an operation at the hospital where he works, expecting to be home in about 10 days. Months later, however, he’s still there when the character of Hideto (played by Eiji Sugawara) is summoned to his father’s bedside by his mother (male actor Takaya Yamauchi) because his father is about to die.

It’s revealed that the hospital has made some mistakes, but more baffling to Hideto is the behavior of his parents, who have barely spoken to each other in decades. Hideto watches them reminisce and laugh together, and is even more stunned when he sees how nice his father is to the doctors and nurses, despite having been a tyrant at home.

“When I did this play two years ago the events were really too recent to handle coolly and calmly, but if I hadn’t written it then I would have lost the feeling,” Iwai says. “So this is a very primitive type of play, but it’s very faithful to basic human instincts.

“However, I’m revisiting it now with a different state of mind, so I’m tackling its core point — that life is neither simple nor straightforward — from a wider perspective.”

Part of this rethink also involves Iwai presenting his actors with a new challenge by urging them to bring their real selves to the stage, not to just act their role, so that together they create a play that’s unique to them and specific to that time.

“These days I think more about the meaning of each actor’s existence,” Iwai says. “They are not replaceable puppets, and there needs to be a reason why they play their role how they do on stage.”

For some time now, the director has been putting this idea into practice in theater workshops he has conducted with students and amateur actors, typically asking them to write about notable episodes in their lives and choosing a few on which to build performances.

“The idea really took off when I created Wareware No Moromoro (All Kinds Of Things About Us) in that way with the seniors’ company Saitama Gold Theater in April,” he says. “The older performers were spontaneous and spoke freely, and I think that was because the play was their actual story. In all honesty, they were often too free and would speak without any cues from me! (Laughs) But they all told me they had great fun doing theater.”

Iwai sums up by stressing how important it is that “theater makes both the actors and the audience question their own lives and identify with what is happening on stage.” Then, perhaps speaking from his hikikomori experience, he adds: “Of course, most situations are impossible to explain logically in words.”

This article originally appeared in The Japan Times on August 15, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.