A young woman with no family to fall back on earns a meager living as a shopgirl but her salary is hardly enough to cover the expenses incurred by her job [the uniform, etc.], nevermind the fines received when she does not perfectly follow the house rules. News of a surprise inheritance comes just in time to spare her a turn on the streets but rather than save the money, the woman decides to buy herself nice things and travel for the first time in her life. Though her fellow shopgirls urge her to reconsider, the young woman insists on going ahead with her plan. “I have had six years of scrape and starve – now I’ll have a month of everything that money can buy me – and there are very few things that money can’t buy me – precious few.” The young woman is Diana Messingberd and though she might just as easily have been dreamt up by any number of modern playwrights exploring inequity in the lives of working women, she is the creation of Cicely Hamilton’s “Diana of Dobson’s – a play that was first performed in London in 1908.

Clockwise from center: Rhonda Aldrich,

Kendra Chell, Jazzlyn K. Luckett, Erin Barnes.

Photo by Geoffrey Wade Photography.

Friend of George Bernard Shaw’s, a member of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League (an organization dedicated to securing equal rights for women via their use of the pen) and founding member of the Actress’ Franchise League (also dedicated to securing votes for women) among other things, Cicely Hamilton (1872-1952) focused her creative efforts on making sure women could achieve financial security as a path to discover their own strengths as an individual. Antaeus Theatre Company’s decision to bring Ms. Hamilton’s play to their stage is a smart and timely one, though, from the looks of how little things have changed for women in 110 years, one is tempted to wonder whether this play will ever be anything other than timely. Dramaturg Rachel Berney Needleman helps set the tone of the world quite successfully before we even hear the first sound cue by contributing program notes on ‘Diana’s World’ that describes the fiscal equivalents from Diana’s time to ours. For example, 6 pence equals $7.50 with £13 pounds being the equivalent of $11,000. This might seem like nothing more than a bit of trivia but early in the first act, Diana lets us know she makes £13 a year and when a co-worker and co-dorm-habitee Miss Smithers reminds her that the firm prefers assistants don’t discuss salaries, Diana counters with “I don’t wonder – I’m glad the firm has the grace to be ashamed of themselves sometimes.”. Companies still discourage salary discussions – possibly for similar reasons and just for comparison, in the United States, the Federal Poverty Level guideline for an individual is $12,490.

Jazzlyn K. Luckett, Lynn Milgrim, Ben Atkinson.

Photo by Geoffrey Wade Photography.

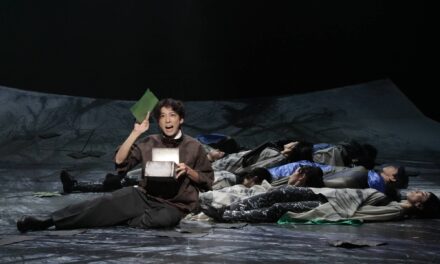

Director Casey Stangl delivers a beautifully crafted world where the plight of women, if not servants in general, is both underscored and used to delightfully comic ends. After a first act that takes place in the shopgirls dormitory, the action shifts to the Hotel Engadine in Switzerland, however the furniture is little changed in appearance until the cast of shopgirls now turned into a small army of servants plus one waiter turn the sad cots and simple wooden chairs into luxurious-looking furniture and a grand fireplace with the assistance of slipcovers and clever choreography. Miss Smithers (Desirée Mee Jung), Kitty Brant (Erin Barnes), Miss Jay (Kendra Chell), Miss Morton (Jazzlyn K. Luckett) become ‘seen but not heard’ servants who are always at the ready to catch a tossed walking stick or hold out a purse and gloves when the time is right. In-between those times, the four women go about their routine tasks with a wistfulness in some, a determination in others that might suggest they have no internal life but as the action unfolds they grow to be just as amused and light-years more aware of Mrs. Messingberd’s situation, even if they only reveal it with a suppressed smile or a little look. Now in the world of the wealthy, we meet Mrs. Cantelupe, played by the vocally commanding and physically talented actress Rhonda Aldrich (in the first act, she takes the role of Miss Pringle, the domineering, easily shocked house marm overseeing the girls). Concerned that her nephew, Captain the Hon. Victor Bertherton is so taken with Mrs. Messingberd that he’s ready to fall into a trap at any moment and well aware that his inability to live on his mere £600 a year puts him in need of finding a wealthy wife, Mrs. Cantelupe engages the help of Mrs. Whyte-Fraser (Lynn Milgrim, who is an utter delight) to lure Victor away so she might interrogate Diana.

John Bobek, Abigail Marks,

Tony Amendola and Lynn Milgrim.

Photo by Geoffrey Wade Photography.

We then see Diana in all of her Paris-fashions glory and if she wasn’t already clearly a force to be reckoned with, the way she maneuvers those ‘above her station’ prove she’s worth more than all of them put together. As Diana, Abigail Marks is mesmerizing. She brings a kind of Mae West energy – all-knowing without the nudge and wink – her eyes dazzled by the sights around her, her mind never losing focus on her purpose for being there. When she is on stage, she’s all you want to witness, which is why we are so lucky she has John Bobeck to play off of. When Diana is absent, his Victor falls into what we might assume are his worst habits of taking things for granted and failing to examine life but when she’s around, he is physically charged by her presence and it is a lot of fun to watch Mr. Bobeck grapple with that. These two characters never really end up at each other’s throats – no matter what is revealed about the other, there isn’t hatred at the bottom of that well – but they keep each other off-balance in a series of arguments that are sparked when Diana realizes she must leave due to lack of funds and Victor realizes he wants to marry her. She might have said yes were it not for the presence of Sir Jabez Grinley (Tony Amendola), a recently knighted owner of shops who has no problem admitting that his money landed him the honor (he is worth £40,000 pounds a year – you don’t need math to sort out that he’s a millionaire). He asks Diana to marry him before Victor does but Diana’s recollection of what it is like to work for the likes of Mr. Grinley is all too recent and far too deeply ingrained for her to say yes to such nonsense and further fuels her desire to go.

John Bobek, Lynn Milgrim, Abigail Marks.

Photo by Geoffrey Wade Photography.

She comes clean with Victor and in the midst of the fight that ensues after she reminds him they haven’t even known each other for two weeks (take that, Rom-Coms) she takes fault with him for looking down on her for earning her own living when he never has and states she “imagine(s) you would find the answer to be that under those circumstances, the world hadn’t any use for you.”. She doesn’t believe he would last six months out there on his own. In the third act, Victor tests her theory, determined to see it through in spite of the realization that she was right, he cannot find work that pays much for long. While sleeping on a bench along the Thames, a Police Constable Fellows (played by Ben Atkinson, who also took on the role of Waiter at the Hotel) tries to convince him to change his mind but he remains as stubborn as Diana was in her intention to leave him in Switzerland. When the Woman sleeping next to him on the bench wakes and asks him what the matter is, “I was only thinking what a silly fool I am,” he replies Her reply, “We’re all of that – dearie – or we – shouldn’t be here.” feels more globally accurate than Hamlet’s assessment of philosophy. Inevitably, Diana comes seeking a place to sleep and ends up sharing the bench with Victor and the Woman, who eventually wakes up again and leaves to ease their conversation. Victor has learned the value of money and swears never to waste it again while Diana admits her pride is the only thing keeping her from saying yes when he begs her to help him find the way via marriage. She says yes and he uses a coin borrowed from Constable Fellows to buy them breakfast.

John Bobek and Abigail Marks.

Photo by Geoffrey Wade Photography.

When Victor exits the stage to purchase the food, there’s a moment when Diana is left alone and we aren’t certain whether she’s full of fear that he might not return or sad at the thought of marrying but there’s a moment where we also fear she might flee before he comes back. Thankfully, she remains seated and he returns. Though he has a lot to learn about what it means to live without that silver spoon in his mouth, we are able to hope that these two might not just be fine, but actually quite perfect for each other.

The creative team at Antaeus once again delivers beautiful work. The scenic design by Nina Caussa is both clever and evocative. Costumes designed by A Jeffrey Schoenberg help to sharpen the contrast between the worlds we visit while also revealing a lot about the characters (Miss Pringle’s oversized bonnet, Mr. Grinley’s beige and white suit that reveals he’s no longer likely to get dirty on the job). Lighting design by Karyn D. Lawrence shapes the space without drawing our focus and props designed by Katie Iannitello add texture and dimension. Above all, the sound design by Jeff Gardner is layered and evocative – it might be the most successful of all the elements and that’s saying something with a bar raised this high. Nike Doukas is the dialect coach. The production stage manager is Heather Gonzalez. The production is partner-cast with the exception of Ms. Marks and Mr. Bobeck.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christine Deitner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.