Jackie Sibblies Drury is one of the most exciting voices working in American theatre today. The Pulitzer Prize-winning writer of Fairview and We Are Proud to Present a Presentation… has a way of ingeniously experimenting with form to pose hard-hitting questions about race, power, and representation. Her latest play Marys Seacole, premiering in London three years after its first production in New York, is a worthy successor to this track record with its ambitious subversion of a biographical narrative.

At the center of Drury’s shape-shifting drama is Mary Seacole, the British-Jamaican nurse whose entrepreneurial activities, particularly her work in the Crimean War, made her a pioneering, if underappreciated, figure of nineteenth-century medicine. Signaled by its pluralized title, Marys Seacole refracts its protagonist’s adventurous life through an anachronistic prism that broadens the reach of her calling across generations and continents. The result is a series of scenes which vacillate between the 1850s and the present, revolving around ideas of caregiving, maternal affect, and racial inequality.

Throughout, Mary also offers a first-person account of her life, directly addressing us and teasing out her central motivations, particularly her ceaseless drive to help others in a society that intends to keep her in the shadows. As we move from a hospice in contemporary England to Mary’s hotel in the 1850s’ Kingston, and from a playground in present-day US to the Crimean War itself, the play’s characters simultaneously multiply in number and seem to converge upon one another. Mothers and daughters, caregivers and care-receivers find themselves in increasingly bizarre situations where social boundaries, including interracial relations, appear to be in need of constant readjustment.

In the title role, Kayla Meikle portrays the unsung hero (and variations on her) with charged sympathy, gently sliding between stern professionalism and humorous compassion. She receives laudable support from the all-female ensemble: Olivia Williams and Esther Smith meticulously embody a range of mildly irritating women who keep rubbing Mary up the wrong way. Déja Bowens is behind a number of naïve and exasperated characters for whom Mary serves as a harsh mentor. And some of the play’s funniest moments land perfectly thanks to Susan Woolbridge’s elderly personas.

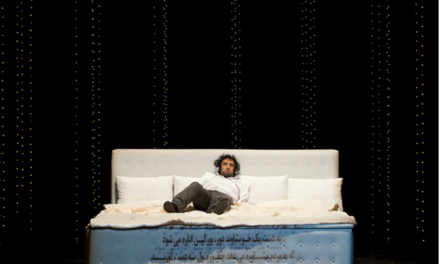

Nadia Latif, who previously directed Fairview at the Young Vic, handles the thorny structure of Drury’s kaleidoscopic drama with assured gestures. Tom Scutt’s set design thoughtfully brings together the play’s diverse settings within the tent of a field hospital, where curtain-like partitions ascend and descend to introduce new scenic elements. These shifts are effectively complemented by Jessica Hung Han Yun’s stylish lighting, which injects each scene with a distinct tonal palette. Xana’s sound design proves similarly crucial to sustaining the fluidity of scene transitions.

Latif’s bold orchestration of these aspects of her staging is especially integral to the expressionist tenor of the play’s conclusion. Here, Drury’s work appears to take us directly into Mary’s war-torn mind, where lines from the previous scenes are echoed with a much darker inflection. The Crimean battlefield gradually morphs into a psychic landscape strewn with corpses of dashed dreams and populated by phantom beings who make vampiric demands on Mary. Mary’s fraught relationship with her mother—implied to be the root cause of her compulsive need to mother others—culminates here in a sort-of confrontation in which Duppy Mary (Llewella Gideon, chilling) delivers a volcanic critique of her daughter’s desire to tend to her white oppressors. “Them need us, but them not want us,” proclaims this ethereal, worldly-wise figure, articulating a dynamic that encapsulates the whole play.

The blazingly abstracted form of this ending makes for a riveting watch. But the same isn’t always true of the prior scenes, where the rhythm occasionally lags and the individually impressive performances struggle to gel with one another. This is perhaps a by-product of the play’s centrifugal structure, an inadvertent effect of its defiant time-travelling. With so much hinging on the porosity of its characters and stories, Marys Seacole seems to demand a production whose pacing and internal recursions are slightly more fine-tuned.

“I give myself power,” declares Mary Seacole with fiery resolve, “I—me.” This self-sustaining spirit of autonomy ultimately finds an apt and compelling outlet in Drury’s palimpsestic drama. Despite its uneven texture, Latif’s production makes a very strong case for why the unorthodox figure of Mary Seacole can and should feel at home in this larger-than-life play.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mert Dilek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.