On Monday, August 31st, 2020, Rattlestick Playwrights Theater presented a benefit concert of Soldiergirls, a new two-person musical with book and lyrics by Em Weinstein and music by Emily Johnson-Erday. Soldiergirls uses real letters and a collage of found and original text to look at love, liberation, and lesbianism in the Women’s Army Corps in World War II. The free online benefit raised money for SPART*A (Service Members, Partners, Allies for Respect and Tolerance for All).

The hour-long presentation was interspersed with behind-the-scenes conversations with the show’s creators that included presentations of research and original artwork by costume designer Sophia Choi and set designer Stephanie Osin Cohen. Both designers agreed to answer a few questions about their work on this remarkable project.

Michael Schweikardt: I’d like to say thank you and congratulations on a wonderfully creative presentation of Soldiergirls. In their introduction, Writer/Lyricist and Director Em Weinstein described the piece as “a two-person lesbian musical sex comedy” and “a mash-up”. I wonder if the idea of collage is something that has been informing your work on the piece as designers?

Sophia Choi (Costume Designer): Em and I believed that the clothes, especially the uniforms, needed to feel realistic and historically accurate in order to firmly establish the time period and setting for the story. But there are moments throughout the musical when our two actors, who play Esther and Marvyl, transform into different personas and caricatures. It’s during these scenes that the costumes break away from the previously established realism, and embrace a more theatrical and playful role, mirroring that “collaged quality” of the script.

Costume rendering by Sophia Choi for Soldiergirls

MS: Stephanie, it was so compelling to hear you speak about the way the theatricality of the piece is informing your thoughts about the set design. I am thinking specifically of your ideas about the scenic space being a performance space. I wonder if you would describe a bit of what you are thinking and why?

Stephanie Osin Cohen (Set Designer): Soldiergirls jumps quickly from scene to scene, changing locations in the blink of an eye, so I knew the space needed to be adaptable, but the concept for the scenic design began with the very first line in the script, which sets the show on an “empty stage”. I began by considering what the empty stage means for us in this world. I started looking into the United Service Organizations (USO) because not only was it established right around the time that our show takes place, it was also created specifically to provide live entertainment for troops – concerts, dances, comedy shows, etc. Soldiergirls really leans into similar theatricalities – jumping genres, engaging with the audience, and blurring the lines between reality and performance. So, I decided to design the set as a place of performance influenced by USO stages. What I came to realize in my research is that Soldiergirls can thrive in a few different orientations: in a traditional proscenium setting, an outdoor venue, or as an immersive/interactive experience. This realization was pretty encouraging considering the nature of our world today and the unknown timeline of our return to the stage. This show really allows for flexibility, and there are so many exciting opportunities in each of these orientations, so we’ll see where this piece goes next and how we can best support the work!

Research image courtesy of Sophia Choi.

MS: Sophia, how does the gender divide manifest itself in something like a military uniform?

SC: I think there’s already an inherent androgyny to military uniforms. But there’s always been this strong (and rather desperate) desire to mark a clear gender division. It wasn’t until recently that the Army decided that their official service dress uniform for women should include pants, rather than a skirt. To some people, that change may not seem significant, but it’s huge. When it comes to uniforms, pants prioritize practicality and functionality; skirts and hosiery prioritize style and traditional “femininity”.

Costume rendering by Sophia Choi for Soldiergirls

MS: Would talk a little bit about how the realities of women in uniform during this period are, as you say, “so much more compelling than the fiction?”

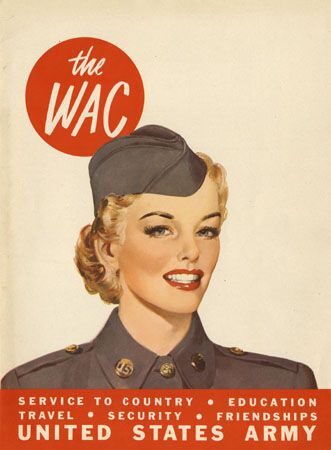

SC: Throughout history, and to this day, we seem to be incapable of separating women and fashion. This was no different for the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Fashion was a strong tool that was used to recruit soldiers, and to subdue any public outcry regarding women joining the army. When you look at the 1940s propaganda imagery produced by the WAC, they genuinely look more like beauty advertisements – the red lipstick, the cinched waists, the perfectly permed hairstyles. And in many ways, when you were a soldier in the WAC, there was a lot of pressure to maintain this pristine feminine appearance.

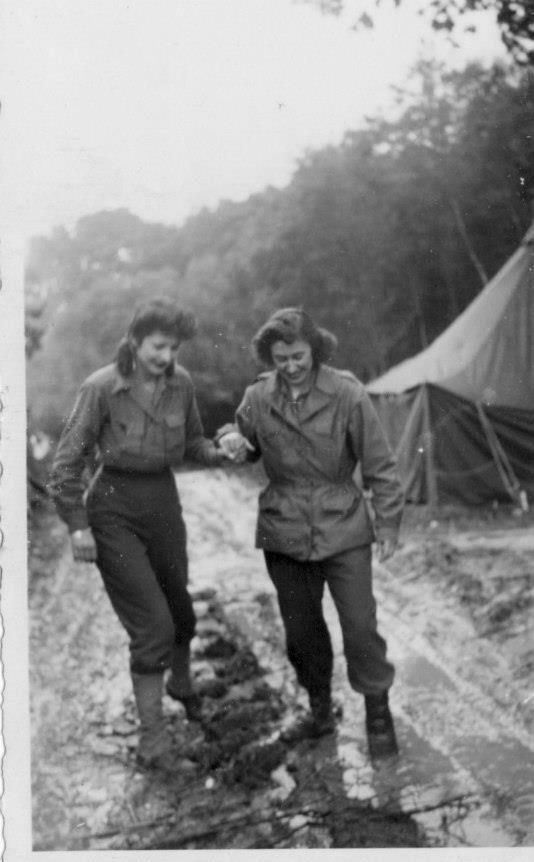

Research image courtesy of Sophia Choi.

But despite these pressures and limitations, many WAC veterans describe their experience in the army as “liberating” in comparison to their civilian lives. In reality, they weren’t “beauty queens” in uniform – they were incredibly intelligent, highly capable, and rigorously trained professionals, who came from all different backgrounds. For once, their worthiness didn’t rely on beauty standards or marital status, but on their individual aptitude. There must have been such a wonderful feeling of excitement and a sense of adventure that came with this newfound independence. Seeing that excitement through these old photographs has been one of my favorite parts of the research.

Research image courtesy of Sophia Choi.

Whether they knew it at the time or not, by the sheer act of joining the army, these women started to alter the collective consciousness regarding gender norms and sexuality. They were met with a lot of prejudice and disapproval by a large percentage of the American population at the time. But when you’re looking through these research photographs, and read interviews of WAC veterans, you can tell these women had the time of their lives serving in the military – prejudices be damned. As a costume designer, I want to be able to provide the actors with that same sense of pride and excitement, through something as simple, and wonderful, as a military uniform.

Research image courtesy of Sophia Choi.

Sophia Choi is a New York based costume designer originally from northern Virginia. Her recent theatre credits include Notes on My Mother’s Decline (The Play Company), Intelligence (Dutch Kills Theater), Anna May Wong: The Actress Who Died A Thousand Deaths (Mabou Mines), and An Enemy of the People (Yale Repertory Theatre). She received her MFA in Design from the Yale School of Drama, where her credits include A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Three Sisters, Young Jean Lee’sLear, and Mies Julie. Sophia is a recipient of the Zelma Weisfeld Scholarship and the Jay and Rhonda Keene Scholarship for Costume Design. She also holds a BFA inTheatre Design & Technology from Virginia Commonwealth University. Website at: sophia-choi.com.

Stephanie Osin Cohen is a NYC-based scenic designer from Miami, FL. Theater design credits include: Richard & Jane & Dick & Sally, Men on Boats (Baltimore Center Stage);This American Wife (Next Door @ New York Theater Workshop); Good Faith (Yale Repertory Theater); LOVE (Marin Theatre Company); Ni Mi Madre (Rave Festival, Teatro Sea); Mrs. Stern Wanders the Prussian State Library (Luna Stage); Pentecost,Much Ado About Nothing (Yale School of Drama); Lear, The Conduct of Life (Yale Summer Cabaret); Avital, Fade, Ni Mi Madre, The Guadalupes, The Slow Sound of Snow, (Yale Cabaret). Film & TV design credits include: Home Exercise (premiered at MoMA and Lincoln center as part of the NYFF); Candace (American Pavilion selection at Cannes Film Festival); Swimminghole (music video featured on Vimeo as a “Music Video We Love”); Drills. Stephanie received her MFA from Yale School of Drama. She is a Fulbright Scholar, and the recipient of the 2019 Burry Fredrik Design Fellowship. Website at: stephanieosincohen.com.

Soldiergirls was previously workshopped with New York Theater Workshop and Rattlestick Playwrights Theater and was made possible by a commission from En Garde Arts. PBS covered the piece in a recent episode, which you can watch here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Schweikardt.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.