The Polish production To The Depths or To The Bottom (Do Dna), which appeared at the 2017 Divine Comedy festival in Kraków in December, has a story as rich as the performance itself.

Originally, the just under two-hour set of reimagined folk songs was the final performance for a class of actors in the vocal performance track at the AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków (Dominika Guzek, Agnieszka Kościelniak, Weronika Kowalska, Jan Marczewski, and Łukasz Szczepanowski). Their director and professor, Ewa Kaim, together with dramaturg Włodzimierz Szturc and music director-arranger Dawid Sulej Rudnicki, led the group of students in the exploration of a folk-music archive.

Gathered throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by the Polish ethnographer and composer Oskar Kolberg, the ethnomusicologist and composer Henryk Gadomski, as well as Father Władysław Skierkowski, the collections bring together hundreds of regional songs. The characteristic open-throated style of singing, often called “white voice” (“biały śpiew”) for the range of tones it can reflect, could traditionally be heard across present-day Poland and Ukraine.

Łukasz Szczepanowski in To The Depths (Do Dna), directed and script by Ewa Kaim. AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, 2016. Photo credit: Bartek Cieniawa

What happened next is the stuff of a theatre legend. As the company drew inspiration from one of Skierkowski’s volumes—The Songs Of The Kurpiowska Forest (Puszcza Kurpiowska W Pieśni)—they developed an unlikely, but unmistakable hit. By its crowded Divine Comedy engagement, the show had seen a variety of festival and other awards—for best production, directing, acting, and ensemble.

Perhaps it was as simple as finding a sweet spot. The ensemble sought to tap their source of the time-honored music in order to develop something new and of their own for the performance. In this way, they joined the lineage of Gardzienice. For more than 20 years, Włodzimierz Staniewski’s theatre has delved into the roots of ancient Greek songs, for example, as inspiration, as it has worked in harmony with its regional community near Lublin.

In their Academy of Theatre auditorium in December, the performers of To The Depths sang the show’s original arrangements and danced Maćko Prusak’s choreography. As Rudnicki played piano or bass, they joined in on the accordion, drum, or violin. The simplicity of the songs’ events—from chores, to changes in the weather, to falling in love—were recounted in a robust gwara, or folk dialect.

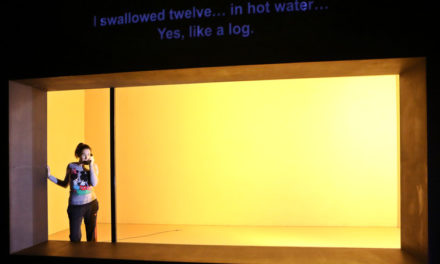

From To The Depths (Do Dna), directed and script by Ewa Kaim. AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, 2016. Photo credit: Bartek Cieniawa

Even more complex were the effusiveness of the voices and the intricacy of the compositions. It almost seemed that it was the sound of the voices themselves that shifted the colorful lights and projected patterns across the set’s suggestion of a country house. (These were all designed by Mirek Kaczmarek, as were the deconstructed folk costumes, adapted for today.) It led us from day to night, winter to summer, as easily as nature itself.

In these resonances, the ensemble also expressed as many emotions as make up the human spirit. As such, the historical context around this musical tradition—with origins in a part of the world also marked by occupations, uprisings, and war—was allowed to live in its songs of heartbreak. Just as viscerally, we were invited to share in the joy of an upcoming wedding, or the boredom of waiting for fruit to fall from a tree. (There were also many songs about blueberries.)

At times, the performers tenderly took on the physicality of the songs’ often much older singers. Here, they showed a sensitivity to their place in this legacy, all while they brought new energy to it.

Agnieszka Kościelniak and Weronika Kowalska in To The Depths (Do Dna), directed and script by Ewa Kaim. AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, 2016. Photo credit: Bartek Cieniawa

Polish folk culture, too—from music and storytelling to visual art—has a story as complex as Poland’s history.

As the country itself shifted on the map, folk music would inspire the rhythms of Romantic poetry. Under Communism, local crafts, dances, and styles of stress were codified into an artificially united national “image.” In Poland today, szopki, or traditional nativity scenes, continue to be crafted in anticipation of Christmas, while souvenir shops sell swag printed with floral paper-cut designs.

With new perspective, Polish street artist NeSpoon works with folk artists to cover city walls in traditional lace patterns. Groups like the Warsaw Village Band have incorporated techniques learned first-hand from rural musicians into their contemporary harmonies. To The Depths seemed to acknowledge its place amid all of these influences.

Jan Marczewski, Agnieszka Kościelniak, Weronika Kowalska, Dominika Guzek, and Łukasz Szczepanowski in To The Depths (Do Dna), directed and script by Ewa Kaim. AST National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, 2016. Photo credit: Bartek Cieniawa

But more than any element of tradition, its artists emphasized what links them all together—people. A culture, of any kind, emerges when individuals choose to come together, in a given context, to create something: a song or a language, a performance or a political system. It is intentional that the show’s title in Polish also spells out “DNA,” the biological basis that connects us all.

Before the show began, interviews with Poles in rural communities played out on speakers around the auditorium, where their voices mingled with the audience’s own excited pre-show chatter. While the recorded words may have sounded a world away to the international crowd present that afternoon, the ensemble’s embodiment of the many voices that made up its inspiration brought us closer together, with every song.

By the end of the show, as the auditorium broke into waves of applause, actors and audience all, we were one.

A special report on Divine Comedy Festival was prepared with support of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute – the national institution of the culture of Poland. To learn more about polish theatre go to http://culture.pl/en/category/performance

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren Dubowski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.