Not so long ago characters didn’t lose their memories onstage, even if on rare occasion actors forget their lines. Yes, we saw Kathleen Chalfont die of metastatic ovarian cancer in Margaret Edson’s Wit. We saw Tony Kushner’s Prior Walter and Roy Cohn dying of AIDS in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America (Walter lives, Cohn dies) , and Jane Fonda as a musicologist succumb to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease) right in the middle of a research project on Beethoven in Moises Kaufman’s 33 Variations. But, unless you think King Lear has Alzheimer’s, when have you seen an older figure with dementia on the professional New York stage?

But now suddenly, in the 2015-16 season, I counted four cases of Alzheimer’s. In fact, a standard dementia plot is emerging: Older Daughter (why is it always a daughter?) is sacrificing her life to caregiving. Should she send Mom to a nursing home? Shouldn’t the younger siblings take more responsibility? Or how about bringing in a robot to keep Mom company?

The latter is the theme of Jordan Harrison’s play Marjorie Prime, which ran for ten weeks last winter at Playwrights Horizons, a theater on Manhattan’s Theatre Row dedicated to new playwriting. In it, the 85-year-old Marjorie (performed by the great 85-year-old stage and film actor Lois Smith) is losing her memory, and her daughter and son-in-law have acquired (bought? rented? leased?—the business arrangement is fuzzy), a “Prime” to simulate Marjorie’s dead husband, Walter, at about the age of 30. The Prime—performed with a marmoreal calm by Noah Bean—is programmed (or “primed,” the word has two meanings) by Marjorie’s son-in-law Jon, who fills him up with family stories. Also in his memory bank are any stories Marjorie can still manage to call up, mostly about the family’s two dogs found at the animal shelter, and her other suitor, a tennis player.

Doesn’t sound very interesting? You’re right. For one thing, what’s up with Marjorie’s life with Walter? If I were Marjorie, I’d rather forget it. And worse, it seemed really hard for Harrison to mix AI and AD in the same plot. In plain terms, the need for reciprocal dialogue between mom and machine was at odds with real dementia. Before you know it, Marjorie remembers too much, the robot knows too little–and, what’s a playwright to do? He calls on the hoary theme of realism that never fails: the clash of generations.

So it seems Marjorie wasn’t a good Mom. To daughter Tess’s everlasting resentment, Mom always favored her dead younger child and Tess’s sibling Damian, who inexplicably–what?–shot himself? Details are offered in shards not so much to replicate the nature of dementia, but to keep the audience following what little plot development there is.

In the last act, Marjorie herself has died, and daughter Tess, who was a settled opponent of AI earlier in the play, is left to work out her childhood trauma with Marjorie’s replicant, Marjorie Prime–yes, another robot–played of course by Smith whom we’ve just seen as Marjorie. Strange to say, if you are a reader of the New York Times you would never have known that Marjorie has been replaced by a Prime, or that the screwed-up daughter Tess is warming to her new robotic Mom. What happened? Did the Times’s Brantley leave the theater at intermission?

As a veteran of ten years of caring for a dementia-stricken parent, I’ll say flatly– Marjorie doesn’t have Alzheimer’s, that’s my diagnosis. So she remembers that her daughter Tess bugs her to eat peanut butter to keep up her weight, and she remembers, when prompted, how she and her husband, the original Walter, got their dog Toni from the pound. If she had really had dementia, and her short-term memory was shrinking, she would by now have forgotten her husband as my mother did my father. If she had, I say– poof goes the play. Of course, maybe she just has mild cognitive impairment, MCI, the latest scary diagnosis from the Alzheimer’s Association as you may have noted from the 10-page supplement on it in the Sunday Times of April 30, 2016. MCI can take years to develop into “full-blown” Alzheimer’s or may never get there. (But if Marjorie has MCI, why is she already dead in the second act?)

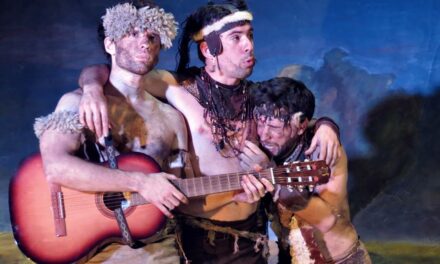

DOT played for several weeks this spring at another off-Broadway institutional theatre, The Vineyard. The leading figure of this new play by the terrific actor Colman Domingo is a middle-class African-American woman in her late sixties, who raised three children in downtown Philadelphia at a time when the neighborhood was just beginning to integrate. Now Dotty (played by the lovely Marjorie Johnson) is losing her memory, and her eldest daughter Shelly is losing her mind with all the caretaking. She’s a grumpy, critical sort, and is furious with her gay brother Donnie, a music journalist in New York City preoccupied with his marriage to a white guy, and with her younger sister Averie, who has made a sensation on YouTube and is trying to launch a singing career. Curiously, the two sisters break into every racial cliché and profanity of “you-go-girl” speech, while matriarch Dotty and her musician son sound as if they were educated at Oxford.

Domingo, a less experienced playwright than Harrison, falls back on a more conventional plot, so there are no robots from the nursing agency, thank goodness. In fact, there is an adorable Eurasian caregiver named Fidel whom Shelly can only afford three days a week. Young, loving, faithful (get it?) and playful with Dotty, every now and then Fidel calls his family in Kazakhstan on his cell phone. This character (played by Michael Rosen) is a charming original amidst the conventions.

The Dementia Plot, above, is mixed with the Family Homecoming plot, so naturally, it is the day before Christmas, and into the house come the three adult siblings, the gay husband Adam, and Jackie–a white woman now living in New York visiting the old Philadelphia ‘hood. As a teenager, Jackie was in love with Donnie. (The neighborhood, now all black, was then a real estate “Oreo” as X calls it.) In a crisis and creating her own personal subplot, Jackie is pregnant by some married guy in New York City, but still hasn’t recovered from Donnie’s coming out of the closet. Hey, Jackie, it was 20 years ago, get over it.

In the second act, the Dementia Plot takes a turn for the better! We may be expecting to see Dotty go off to Assisted Living while the children weep, like Blanche putting her faith in strangers, but Domingo fights off the old clichés. First, Dotty herself takes charge of her own condition just as her doctor said she could. So she gives all the ‘kids’ Christmas presents, components of a “virtual dementa” simulation game. (This game is actually sweeping institutions in the form of an “old age simulation suit,” a performative teaching tool that shows the wearer–an airline hostess, a hospital nurse– what it feels like to be old. It is supposed to displace horror and teach empathy. I have my doubts. If you haven’t heard of it, just put GERT into a Google search.) Anyhow, Dot distributes pebbles to put in shoes, Vaseline to smear on eyeglasses, elbow braces to impede joint movement. And then, in a conversion faster than Saul’s on the road to Damascus, the kids get it! Averie, seemingly the least responsible sibling, makes the best suggestion for Mom’s future: “We have to involve her…She needs to be there, in the conversation, whether she is fully present or not.” Mirabile dictu, everyone agrees! Meanwhile, Averie will move in to take care of Dotty, Shelly will get a break, and Donnie will stop being a self-declared “pain in the ass.”

Sharon Washington, Marjorie Johnson, and Finnerty Steevens in Colman Domingo’s DOT. Photo credit by Carol Rosegg.

But this second act has one other surprising, beautiful moment, which might help to explain how what must have looked like yet-one-more-living-room-play in the script, snagged a director like Susan Stroman, known for her Tony Award-winning direction and choreography of Broadway musicals. At this moment, mid-act, and mid-Christmas Eve, Donnie sits at the piano and rediscovers his old pianistic skill, Dotty begins to dance, Adam fills in as dance partner and is soon taken for Dot’s deceased husband. The moment is sustained. No one speaks. But it is the moment in the play when everyone turns a corner: grows up, calms down, and accepts the future.

And frankly, that is exactly how families cope with dementia, one family at a time. One suspects that Domingo is writing from personal experience. Lucky for Jordan Harrison of Marjorie Prime, that he hasn’t gotten there yet.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Elinor Fuchs.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.