One of the most exhilarating things about Wesley Enoch’s tenure as Artistic Director of the Sydney Festival has been the huge increase in the number of First Nations artists programmed, not only from Australia but also Canada and Aotearoa New Zealand. Festival audiences have had the opportunity not only to witness a local festival being decolonized but also to listen to an increasingly global dialogue through and about First Nations performance.

Like Gabriel Dharmoo’s Anthropologies Imaginaires and Cliff Cardinal’s Huff in the 2017 festival, Deer Woman is a work written, directed, designed, composed, stage managed and performed by First Nations artists from Canada. And like these works, it too is anchored by a solo performance of fierce skill, focus, and precision.

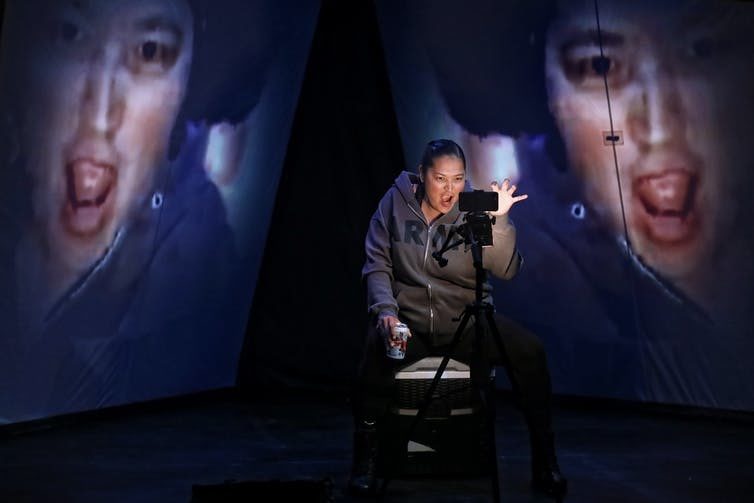

On entering the theatre, we see a sparse set: two screens stand at roughly 45 degrees to the audience and 90 degrees to each other; in between the screens, there is a camera on a tripod and a blue cooler. The screens display infrared footage of deer nosing about in the forest, their eyes glowing green. In the background, the Everly Brothers croon Devoted To You, Walk Right Back, and Love Hurts. The harmonies are beautiful but the titles and lyrics do not bode well.

Throughout Deer Woman, Cherish Violet Blood expertly balances the demands of cinematic and theatrical acting. Prudence Upton

Silence falls, except for the crickets, and Lila (played by Cherish Violet Blood) enters from between the screens. She puts on a hoody, opens the cooler, pulls out a can and cracks it open. It gives a satisfying hiss. “Hey, I’m back,” she says–apparently, we have already been conversing.

Having established that we are in the middle of something–though we are not sure what–Lila begins to set the scene. The first act introduces us to Lila’s girlfriend, Gloria. Lila tells how Gloria, who works at a halfway house, got free tickets to a performance and decided to take the women for an outing. Unbeknownst to her, it featured a woman hanging on a meat hook while a man fisted her. The audience gasps at the inappropriateness, but we are not off the metaphorical hook either.

Instead, Lila teases us about going to see the show, crying a little bit, exclaiming over its “power” and “importance,” and heading home feeling like a good person. “Enjoy your pain porno!” shouts Gloria as she and the women leave at the interval. We, on the other hand, have already been warned that Deer Woman has no interval. How are we going to negotiate for the next 90 minutes?

This mood of teasing, daring and warning the audience shifts into something happier in the second act. Lila stands–finally–and takes us back to her childhood. Her favorite people are Aunty Gary–her mother’s queer brother, who is described as “our only uncle and aunty; we’re really lucky he’s both”–and her sister Hammy.

We then learn about Lila’s sexual abuse, which she decides she can take as long as it keeps her little sister safe, and her young adulthood in the army. It is while she is away that Hammy goes missing. It seems that Lila was protecting a country that still does not protect its own. The third act deals with the aftermath of Hammy’s disappearance, including Lila’s detailed plans for revenge.

Deer Woman is a work of immense power–to invoke the theatergoer mocked in the first act–and, for the most part, restraint. Tara Beagan’s script is immaculately structured, and the language is striking for its specificity (welfare pops, Gretzy, the Chinook, the Sally Ann), poetry (Bob is as “quiet as a stump” and Gary is a “pessimistic cheerleader”), and bleak humour (Gloria claims to attend the “uni of life–you graduate by not getting killed”).

Deer Woman excels because of its solo performer, Cherish Violet Blood. Prudence Upton

The set, by director and designer Andy Moro, is similarly effective. Most of the time, the live performer and the two screens are in sync but occasionally they decouple. One screen might dissolve into footage of the fairground while the other screen might freeze Blood’s face wearing a particular expression. The sound design is similarly understated: we hear the distant cries of people enjoying rides, crowds at a rally, and one sister singing the other to sleep.

None of this would matter though if the wrong person were cast as Lila and Deer Woman excels because Blood does. Throughout the entire show, Blood expertly balances the demands of cinematic and theatrical acting, combining subtle facial gestures within the frame with expansive physical ones beyond it. It is a consummate performance that oscillates between entertaining, confessing to, disciplining, daring and playing with the audience.

Within the context of this year’s festival, Deer Woman serves as an important counterpoint to Adam Lazarus’s Daughter, one of the most conservative shows–in form, content, and politics–I have seen in some time. Indeed, I could not help but think of Daughter in the opening scenes, when Lila is describing Gloria’s disastrous outing to the theatre, which features a “white guy saying real rank stuff.” While both shows are solo performances that deal with gender and sexual violence, that is where the similarities end.

Whereas Daughter employs theatre to amplify the loudest voice in the room, i.e. that of the privileged straight man, Deer Woman puts a queer woman of color center-stage, has her survey the room and speak her desire to destroy it. Indeed, rather than the violence against women, it seemed to be the idea of women taking revenge that shocked the audience. People who had been sitting forward started to lean back, several people walked out, and one woman muttered to her companion “this is horrible.”

Deer Woman features a sparse set. Prudence Upton

Companies often grant reviewers only one ticket, meaning that I regularly see theatre by myself. When a show finishes I always walk briskly and purposefully to the car park or train station, informed by a lifetime of banal advice: walk as if someone is expecting you, keep your keys at the ready, call someone on your phone, don’t wear headphones, do wear shoes you can run in if need be.

But on the night of Deer Woman, I walk more slowly, open my chest and shoulders, feel the strength in my back. There is an army of big sisters out there, I think to myself, and we are coming for you. In the morning, news of Aiia Maasarwe’s murder would break and I would shrink back to my normal size. But for one glorious moment, I was–like Deer Woman–wild and free.

Deer Woman was staged as part of the Sydney Festival.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation on January 17, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Caroline Wake.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.