What do we humans have in common with wales, mushrooms, bacteria or the internet? We are all networked entities. Philosopher Bruno Latour pleads for a radically different perspective on the persistent binaries of human-thing, human-environment or local-global. Latour crosses the boundaries of the academic world and brings his insights to the stage, together with researcher-director Frédérique Aït-Touati.

“Using horror techniques to arouse strong feelings doesn’t make a work political.”

As paradoxical as it may seem, to gain in realism we have to steer clear of every pseudo-realism in which people are portrayed parading in front of a decor of things.

-Bruno Latour

Bruno Latour, the world-renowned sociologist of science and philosopher, caused a seismic shift in academia in the eighties and nineties with his research into the technically and socially constructed nature of scientific knowledge. Facts are, according to Latour, to a large extent the product of interactions between experts, of scientific methodologies and procedures. He demonstrated that, within modernity, the natural and the social were interpreted as two separate worlds, and how that separation impeded insights and had a harmful effect on the social, economic and ecosystems that we are a part of.

In the performing arts, his name and work almost inevitably crop up when it comes to labeling and exploring the agency of objects. Latour is, after all, a passionate advocate of a “parliament of things”: in his view, the human political hemisphere has to be complemented by a hemisphere representing the non-human. An exciting and important challenge. When reflecting on art, Latour’s sociological actor-network theory is relevant as well, as it implies that a work of art doesn’t exist in a vacuum but comes about in a network of actors (people, machines, buildings, conventions, …).

Urgency, anxiety, despair

Over the last few years, Latour has shifted his focus to a specific, very urgent matter: climate change caused by human activity. In his eight lectures on the new climate regime, which were published as Face à Gaïa (2015), the philosopher points out how the separation between nature and culture enables climate denial and climate quietism (the resigned attitude towards climate change), thus stressing how problematic and even catastrophic it is to maintain that separation. Latour builds on scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis’ Gaia hypothesis, which proposes that the earth is a complex, self-regulatory system in which living organisms continually act on their non-living environment, thus sustaining or limiting the conditions of possibility for their own existence and that of others. In principle, human beings are no exception to this tendency, though their impact is now of the overwhelming and destructive kind.

How can we orient ourselves politically within that new climate regime? In his latest book, Où Atterrir? (2017), Latour tries to find an alternative to the opposition between the local and the global that reigns supreme these days. Globalization inspired by capitalism has not led to more, but rather to less world. Natural-cultural uniformity and the centralization of power in the hands of mammoth companies and world leaders don’t combine well with the diversity of ideas, traditions, lifestyles, ecosystems, etc. that the world consists of. Moreover, the impoverishing effect of globalization leads to a surge in nostalgic nationalism, which in turn reduces the local to a fictional history and a limited idea of identity. Together with climate change, these tendencies wiped out the ground from underneath our feet. We seem to find ourselves in a plane with no destination, Latour writes. Where can we land?

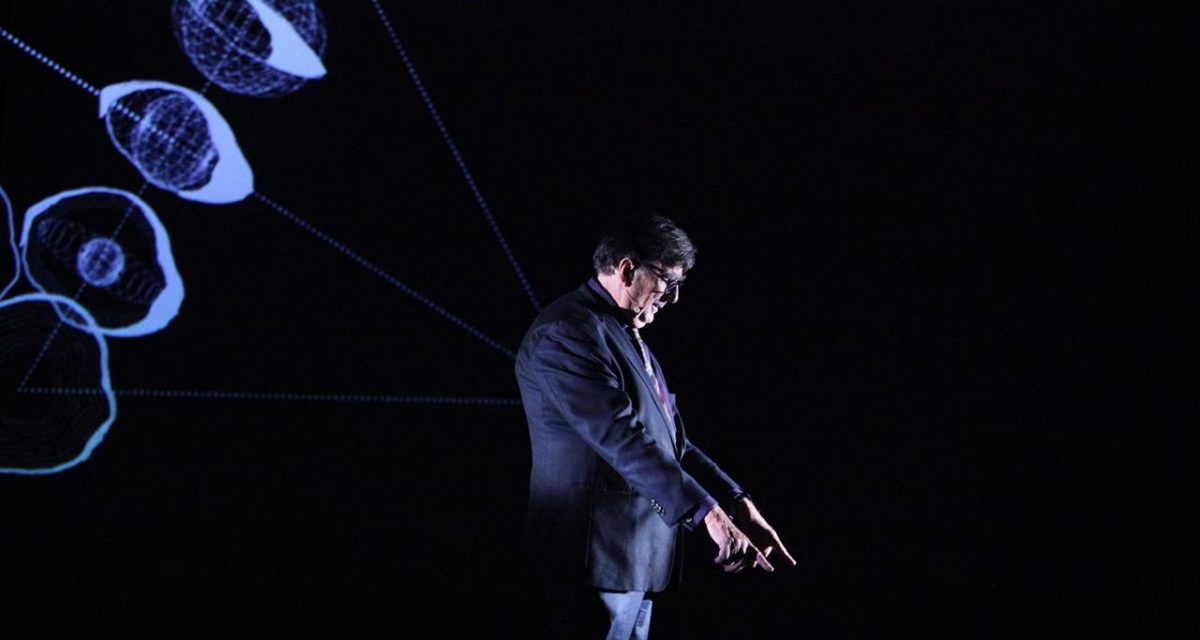

Maybe in the theater. In recent years, Latour has left the academic world every now and then to venture into the artistic world. In addition to exhibitions like Iconoclash (2002) and Making Things Public (2005), he collaborated with researcher and director Frédérique Aït-Touati on theater projects like Gaia Global Circus (2013), MAKE IT WORK/Le théâtre des négociations (2015) and the lecture performance INSIDE (2017). The latter was brought to the Kaaitheater at the end of November 2018, and that was the occasion for this conversation.

ETC: Another alarming IPCC report on global warming has been published only two days ago (October 8th). The sense of urgency related to climate change is not new, but mounting rapidly. Mr. Latour, was this the main reason why you have been taking on a more public position as a philosopher?

LATOUR: For me, there were two entries towards the artistic. Twelve years ago, I saw a couple of shocking charts in a book by Clive Hamilton, predicting ecological disaster if we didn’t act radically upon global warming. You can find the same ones in the IPCC report, except that the curves of the red lines in the charts are even steeper! Back then I got seized by the urgency and decided to re-invest in this strong interest of mine–Gaia–but in a more dramatic way. Frédérique and I assembled a small team and started working on the staging of the “problem” of climate change, which some years later led to the theatre piece Gaia Global Circus.

AÏT-TOUATI: As a historian of science and stage director, I have always been interested in the links between theatre and science. When Bruno suggested that we should work together on the urgency of climate change, I saw it as an opportunity to explore the heuristic (a systemical methodology to do research new solutions and insights, ed.) powers of theatre. Hence the idea to develop theatrical research with my actors, the writer of the play Gaia Global Circus, Pierre Daubigny, and Bruno; a process of research-creation that lasted for three years, and involved fieldwork, readings, improvisations and discussions with several climatologists.

LATOUR: I noticed there is a feedback loop between my work in the theatre and my academic writing. I had to do a lot of reading for the Gifford lectures (which formed the basis for the book Face à Gaïa, ed.) and this fed the play. On the other hand, the discussions with the team and the improvisations of the actors formed the inspiration for the lectures. I don’t consider myself to be an artist, nor doing art. However, constructing a play pushes me to sharpen philosophical concepts. It may be a weak definition of art, but the practical artistic work helps me to grasp ideas which are still half-obscure, hidden in the shadows.

Bruno Latour & Frédérique Aït-Touati

ETC: How do you deal with the feelings of doom and despair in your theatre projects?

LATOUR: We delve into the question of the current sources of indifference to catastrophe. It seems the steeper the curves of the red lines get, the less people react to it. Why is that the case? Theatre also permits us to disseminate anxiety under another form. I don’t think Frédérique and my daughter Chloé, who also collaborated on Gaia Global Circus, were so anxious about the situation when we started working, but I’m sure they’re anxious now! When presenting a play, you spread this anxiety amongst the public, but you also have the opportunity to provoke alternative feelings. You can move from anguish to exhilaration for example. There are so many possible affective ways to relate to the new climate regime.

AÏT-TOUATI: From the beginning, one of our big questions was precisely how to deal with those feelings in relation to theatre. The theatre is an art of specific passions and emotions, which are different from for example those of cinema. It’s impossible to transfer the pathos of a blockbuster catastrophe movie to the stage. Through a series of little scenes and sketches, Gaia Global Circus explored anxiety and despair, counterbalancing it with a good deal of humor. Black humor. One of Bruno’s strong references is the comic strip…

LATOUR: Mainly Tintin, which is maybe not so surprising! Frédérique and I wanted to present various positions, including the one of indifference, and the belief in a technological fix.

Reenactments and reenactments

ETC: What was the second entry for your excursions in the arts, or more specifically the theatre?

LATOUR: I have a background in the history of science. In my book on Louis Pasteur (Pasteur: guerre et paix des microbes, 1984, ed.), I introduced the notion of the ‘theatre of proof’, which refers to the staging, the dramatization of scientific proof. With Frédérique, I share a long time interest in science as drama.

I introduced the notion of the “theatre of proof,” which refers to the staging, the dramatization of scientific proof. With Frédérique, I share a long time interest in science as drama.

-Bruno Latour

There also was a time when science had to rely on the powers of fiction, in order to be able to revolutionize the concept of the earth. Take the work of Johannes Kepler in the 17th century, for example, something Frédérique has also written about. Afterward, modernity drove a wig between literature and science, but I believe the two realms are converging again in our times, reopening the possibilities of expression. It’s interesting to see how the affects modified by the new climate regime are explored in poetry, theatre, the visual arts, …

AÏT-TOUATI: In the past, Bruno also staged Pasteur! He made reenactments of scientific lectures and experiments. In my own research, I have studied the period when science, literature and the arts were deeply intertwined. I think one of the reasons why I started to work together with Bruno is that I feel that our present times are in need of this convergence again.

LATOUR: I staged Pasteur together with my colleague from Cambridge, the historian, and philosopher of science Simon Schaffer. I also did a reenactment of the catastrophic 2009 Copenhagen climate summit. That project was a way to lure people out of their depression by investigating what went wrong and how these kinds of political negotiations could be improved.

ETC: Reenactments are very present in the contemporary performing arts field. In 2015, you made a pre-reenactment of the COP21 in Paris, some months before the actual summit took place.

LATOUR: Indeed. Together with more than 200 students from all over the world, and with Laurence Tubiana, who was an ambassadress to the real COP, we speculated about an entirely different set of rules and procedures for the climate negotiations. The theatre director Philippe Quesne took care of the scenography, the Berlin-based collective RAUMLABOR designed the furniture, and Frédérique staged the weeklong experiment. MAKE IT WORK/Le théâtre des négociations dealt with a topic I have been investigating since my book Politics of Nature (1998), or even since We Have Never Been Modern (1991), namely having human beings speak in the name of nonhuman entities.

De-centering the human actor

ETC: Many of the theatre and performance practices inspired by your work are looking for ways to de-center the human on stage, or even erase him or her altogether. In your collaborative work, whether it takes the form of a theatre play, a lecture performance, a pre- or reenactment, humans stay the main actors.

AÏT-TOUATI: How can we deconstruct theatre as a traditionally human-centered art form? In Gaia Global Circus we used a canopy which flew over the stage with the help of helium balloons. The idea was to have a fifth nonhuman actant next to the four actors. It didn’t prove to be a real success, because the canopy was a puppet that couldn’t move by itself but needed to be moved. I’m not sure if erasing the human presence is really interesting from our perspective. It is rather a matter of combining, shifting the perspective, putting the human and nonhuman together on stage.

LATOUR: Our point is not to erase but to ‘stretch’ the human in order to include the nonhuman. Total absence would be ridiculous. Why would anyone want to come to the theatre just to see the decor basically? We are seeking another relationship to scenography, by–yes–de-centering the human, moving him or her slightly off stage so to speak. Actually, this has always been the case in the history of theatre. The human has always been de-centered by other forces like faith or divinity on stage, forces made visible by the text.

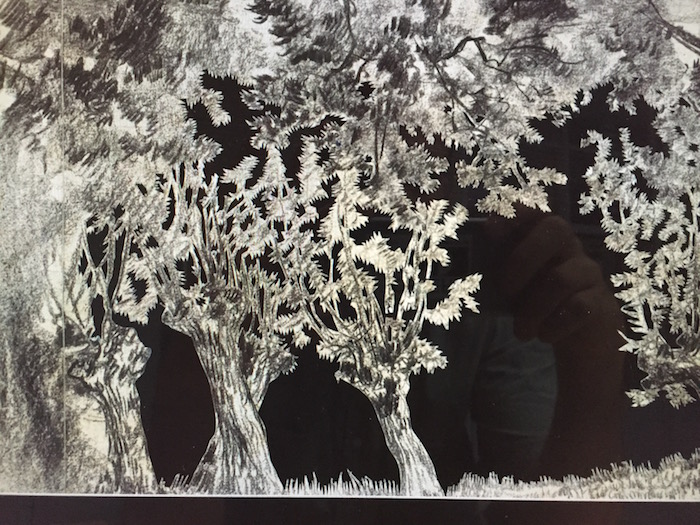

Photo credits: Decor archives of De Munt

AÏT-TOUATI: Decor is not decor anymore. In many of Bruno’s texts, but also in those of Isabelle Stengers and others belonging to the same philosophical family, the image of the backdrop keeps reappearing. They mention how it merges with the foreground and becomes active. This has been key in all the projects I have staged since Gaïa Global Circus in 2013 now also in Galileo Redux, our new project on Galileo and Lovelock, who developed the Gaia hypothesis together with Lynn Margulis.

Our point is not to erase but to “stretch” the human in order to include the nonhuman.

-Bruno Latour

ETC: What does this de-centering mean for storytelling? Just like that other family member, Donna Haraway, you often stress the necessity of changing the way we tell stories nowadays.

LATOUR: We can’t pretend anymore to distance ourselves from the world and describe it. There is the quasi-philosophical argument that the world itself is a narrative – in which we take part. It currently seems to have a strong impact on the arts. Take Richard Powers’ latest novel for example, The Overstory (2018), in which the lives of trees play a pivotal role. The book helps you get closer to the way life forms are in the world through imagining their stories, including the stories of their entanglements with us, human beings. I heard Powers was recently approached by someone from Game of Thrones!

I don’t know of any theatre text that does something similar. It would be really interesting to try this out. On the other hand, theatre dealt with divinity for ages, prior to the modernist divide. Maybe we shouldn’t de-center the human but bring back to the definition of the human what has been taken out of it.

Photo credits: Decor archives of De Mund

ETC: To what extent are these other kinds of stories devoid of suspenseful action?

AÏT-TOUATI: We discuss boredom a lot… The traditional definition of a gripping story involves a protagonist, psychological development, morally good and bad actions. However, when you read scientific literature, you discover the description of things and their agencies is all but boring. We need to get rid of the common sense idea that when it’s not human, it’s not interesting. Think of the stories Anna Tsing tells about the Matsutake mushroom in The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015). That’s what I call gripping!

We need to get rid of the common sense idea that when it’s not human, it’s not interesting. Think of the stories Anna Tsing tells about the Matsutake mushroom in The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015). That’s what I call gripping!

-Frédérique Aït-Touati

LATOUR: With Nature’s Metropolis (1992), William Cronon has written an absolutely fascinating long term history of the city of Chicago. It traces how a place where there was nothing besides a village of native Americans developed over hundreds of years into a metropolis, technically and economically. Within that evolution, humans were–self-evidently–important actors, but they were not the only ones generating the Chicago metropole.

Inside the critical zone

ETC: In the lecture performance INSIDE you argue we should stop imagining the earth as a globe, seen from the outside. Even when seated in an airplane, we are ‘inside’ the critical, fragile stratosphere of the earth, and are exerting an influence on it. This radically different perspective blurs the divide between the local and the global. We wonder what it could mean for the performing arts, where the tension between these two poles is also an important topic of debate.

LATOUR: The local-global divide is a product of globalization. I am looking into different metrics, determined by what I call the terrestrial. This metrics is entity-dependent: what we name “global” and “local” should actually be redistributed for each 0entity. A whale, for instance, is completely globalized in its own way, going from the north to the south. Anna Tsing’s mushrooms are globally disseminated beings, but are only found in particular places, such as forests in the west of the US. Bacteria are not globalized in the way the internet is globalized. And so on. The same goes for us. We are not local in any sort of traditional sense, even though there are now people who desire to be local in a neo-traditional manner. We have to invent new metrics, new data, for this very old situation.

AÏT-TOUATI: At a certain point in INSIDE you can hear a very strong sound, which takes you to a particular locality. It is the sound of the Apollo 8 capsule from which a picture of the globe was made, this blue marble floating in space. It’s an image that is extremely rare but which has a disproportionate impact on our imagination of the earth. In order to create that picture, you had to be in a very small and isolated space. With INSIDE, I don’t think we found a way to make the audience experience the terrestrial, but maybe we could convey how the perspective of the globe is ‘wrong’.

ETC: We traditionally call the experience of an encounter with something that is too big to comprehend, which terrifies and fascinates us simultaneously, “sublime.” Is it still a useful category in the frame of the new climate regime?

LATOUR: In the lecture performance, we actually try to show that the sublime has disappeared because we are all inside. There is no outside anymore that would enable the necessary distance from which to experience and contemplate the sublime. The feeling of greatness caused by the difference in size between you and the thing you see, the immensity of the tornado or volcano you encounter, is gone. Since we are now at the size of the volcano or tornado.

However, you can shift to a dark neo-sublime nowadays, a profoundly perverse delight in the extent of the disaster. The sublime has been replaced by a sort of pornography of catastrophe. I think about the horrifying kind of eco-theatre confronting the audience with environmental catastrophe, written by people who have no knowledge and interest in science. In a blank, abstract way, they evoke these boundless powers. In visual art, you often see the immensity of waste dumps or oil fields for example. It’s also present in a lot of eco-ideological propaganda. I compare it to those grueling books about Nazi doctors. There is a sort of complacency, a very perverse one, where you feel good about the catastrophe. And it has absolutely no political effect in terms of raising consciousness.

The sublime has been replaced by a sort of pornography of catastrophe. I think about the horrifying kind of eco-theatre confronting the audience with environmental catastrophe.

-Bruno Latour

AÏT-TOUATI: Using horror techniques to arouse strong feelings doesn’t make a work political.

LATOUR: Maybe someone like James Lovelock, when he was nearly a hundred years old, could have had the sensation of the sublime. The perspective of this long stretch of time could generate the distance enabling him to say: look how this great civilization has destroyed itself… It remains an interesting question in relation to art history. We know when the sublime erupts, but how could we study the current disappearance of the sublime caused by the ecological question?

ETC: In your latest book Où Atterrir? you refer to the theatre’s architecture when discussing the perspective of being inside. You mention we need to take the frame and the wings of the theatre into account. There is of course also the audience-stage divide, the whole theatre machinery, the painted backdrops or infinite… How can we bring the perspective of the inside into the actual theatre?

LATOUR: The history of theatre and its architecture are strongly influenced by a “specular scopic regime”, a mirroring type of gaze. However, it might not require many changes in the whole architecture to get completely different readings. We are not obsessed with the idea of going outside of the theatre, playing on street corners, or in places which have less defined shapes and no suggested perspectives. Once the critique has been made about the imposition of a specific perspective, in this box which is the theatre, we find ourselves, funnily enough, and in a very powerful manner, inside.

This article was originally published in Etcetera on January 1, 2019, and has reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sébastien Hendrickx and Kristof van Baarle.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.