To read Part 1 of this interview, click here.

Nahm: Let’s talk now about Texas Aunt. I said earlier that The Wooden Boat is a great Korean play to introduce to international audiences. But Texas Aunt already feels like an international play. I don’t think I’ve read another Korean play that has such a racially diverse cast of characters. Frankly, I was a little shocked when I read the character list. How did you come to write this play?

Texas Aunt SynopsisTexas Aunt is set in the rural farming community of Goesan in South Korea. Choon-mi had left her hometown a long time ago to start a new life in Texas with her American G.I. boyfriend. But once she realized she was tricked into farm labor, she flees back to Korea, hiding from her hometown in shame. The play then fast forwards thirty-six years to the present time. Choon-mi’s older brother has brought home a young woman from Kyrgyzstan, who agreed to marry a man over three times her age because she hoped to improve her life in Korea. The migrant woman fits a growing pattern in South Korea where men in rural areas solicit foreign brides because of the gender imbalance in the local population. Often becoming victims of racism, domestic violence, and neglect, some women return to their home countries, leaving behind mixed-race children like So-Chul in the play, whose mother is Cambodian, and the nameless neighborhood kid, whose mother is from Bhutan. Aware of such injustice and exploitation, Choon-mi and the Kyrgyz woman’s step-daughter (only three years younger than her) tries to persuade the newcomer to return home. But the Woman from Kyrgyzstan insists on getting an education in Korea, whatever it takes. Playwright Yun Mi Hyun offers a sobering look into the grim reality of rural life in contemporary South Korea. The play connects the current plight of migrant women in Korea to the country’s own tarnished history of migration to developed countries. Finding echoes in women’s experiences across countries and generations, Texas Aunt shows how easily a society can forget its own painful history to become another perpetrator of violence. |

Yun: Like I said earlier, my plays are about how injustice against the marginalized becomes so pervasive that people don’t recognize it as such anymore. If you get even a little bit away from Seoul into the country, you see all these ads that say, “International Marriage,” “Filipino Women,” “Mongolian Women,” and so on. It’s shocking to see banners like that out in the open about meeting foreign women, although they’re not as visible nowadays thanks to women’s and human rights groups. This has become a big social issue in Korea, mostly in rural farming and fishing communities. The problem is that most Koreans don’t have empathy for these migrant women. Our society discriminates against them, directly or indirectly, rather than console or help them.

Nahm: Aside from your point about international marriages and the treatment of migrant workers, I also find Texas Aunt interesting because it exposes the ideology of ethnic purity that is still deeply entrenched in Korean society. This ideology becomes another source of violence towards migrants and their children. Migrants, especially from Southeast Asia and Central Asia have settled in Korea for a long time now, but most doors are still closed to them socially. No matter how long you’ve lived in Korea and have a family here, it’s hard to be accepted as Korean.

Yun: I agree. This phenomenon of soliciting foreign brides has existed in Korea for 30, 40 years now. But Korea still doesn’t welcome them, neither in terms of public sentiment nor policy. When Texas Aunt premiered at the National Theatre Company of Korea in 2018, Jin Sun-mee, then Minister of Gender Equality and Family, came to see the production with a group of migrant women. And I saw these women cry throughout the performance. We had a post-show discussion, and some of the women who had married into rural farming communities said that they experienced similar things as the scenes in the play. I didn’t know how to respond, seeing all these women cry. I was afraid that I had caused more pain for them. That’s something that I’m always mindful of. When I evoke someone else’s pain or trauma in my writing, I want to make sure that I don’t cause more harm. So, I asked whether they were hurt by what they saw. And they said no. Instead, they felt it has taken too long for these conversations to happen out in the open.

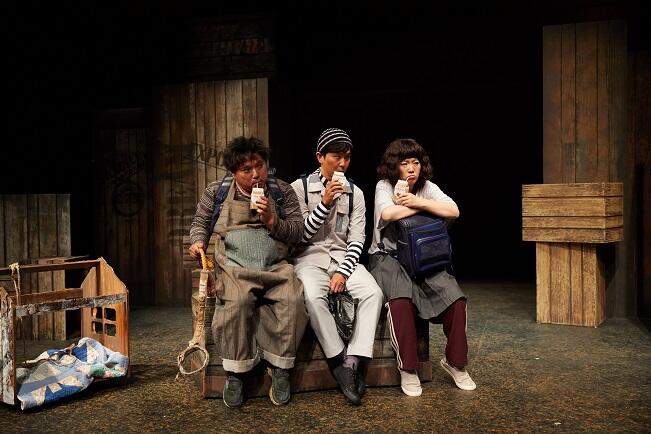

Texas Aunt, by Yun Mi Hyun, directed by Choi Yong-hoon, National Theatre Company of Korea production (2018). Photo courtesy of the National Theatre Company of Korea.

Nahm: I see. They had been crying regardless. It’s just that they were invisible before. At least, now they can share their pain with other people in the theatre.

Yun: They told me they have heard plenty of political slogans about migrant issues. But they’ve never seen themselves represented in art.

Nahm: You said earlier that you see Mr. Chae at the center of The Wooden Boat. Does Texas Aunt also have a main character? The title refers to Choon-mi, but she seems more like an observer of the events in Goesan County. I think that other characters like the Woman from Kyrgyzstan or the Adolescent Daughter stand out as the next generation of women who are grappling with these issues.

Yun: I don’t think there is just one main character in Texas Aunt. Actually, I think that the mixed-race children, So-chul and the Neighborhood Kid, might be at the center of the play, even if they don’t stand out. I think I created characters like Choon-mi and the Woman from Kyrgyzstan as a way to get to the stories of the mixed-race children in the neighborhood.

Nahm: Thinking about some of the older characters in Texas Aunt and The Wooden Boat, it seems like victims of violence and exploitation often become passive characters. It makes sense dramaturgically, since they have to have been in this situation for a long time by the time that the play begins. The reason I focused on the young female characters is because they seem to have the potential to bring about change in the future. These characters remind me of the feminist movement today. Of course, feminism is primarily concerned with women’s rights, but feminists also emphasize solidarity with other marginalized groups, especially with regard to race, ethnicity, and immigration status. Feminist thinkers have also exposed hidden forms of violence in everyday life and the domestic sphere. I think that your play shares those concerns.

Texas Aunt, by Yun Mi Hyun, directed by Choi Yong-hoon, National Theatre Company of Korea production (2018). Photo courtesy of the National Theatre Company of Korea.

Yun: When Koreans talk about feminism, we talk about the social disadvantages that women face. But we don’t talk as much as we should about the rights of migrant women. So, migrant women are doubly marginalized. But if I had decided to consciously write a play about feminism and the rights of migrant women, the play wouldn’t have felt natural. Instead, I thought about how these issues have become a part of our everyday reality and that no one cares about these disenfranchised people. It was only after I finished writing that I saw how it could be seen as a feminist play.

Nahm: Korean society is changing, and your play accurately captures those changes. I want to shift gears to a different aspect of the play. I think that the opening scene is quite ingenious. The prologue takes place thirty-six years ago in Texas, when Choon-mi realizes that she’s been tricked into working on a farm. This scenario felt familiar to me: a story of immigrants in the U.S. talking about their struggles and their longing for the motherland. But the next scene skips forward thirty-six years and is set in Korea. We learn that Choon-mi actually came back home a long time ago. That was an interesting twist. It subverted my expectations about what kind of story this will be. It was as if the play was telling me that Korean society has changed a lot since those late-twentieth-century stories of immigrants toiling away in developed countries. Now, Korea has become a destination for migrants, and bears responsibility for exploitation and marginalization.

Yun: My nickname is blue frog. [A reference to a Korean children’s tale about a contrarian frog who always does the opposite of what his mother tells him to do.] I never do what people expect. It’s not on purpose. I just think that’s my personality. People say that I am quirky, but that’s what feels natural to me.

Nahm: Well, theatre is an artform where unexpected surprises can be especially effective. So, you should keep that up. May I ask what you are working on now or have planned for the future?

Yun: I’ve been wanting to focus on the intricate emotions of one individual for several years now. I’ve had this idea since before the pandemic. A lot of playwrights explore the emotions of individuals only to the extent that they are socially relevant. Even in daily life, I feel that human beings are lumped together into these big groups and ideas, without paying attention to what each person actually feels. That made me want to write a play that takes a microscope to an individual’s emotional life, paying attention to all the little details.

Nahm: Now that you say that, both The Wooden Boat and Texas Aunt feature characters that are anonymous to some degree. We don’t know Mr. Chae’s full name. The only character in the play whose full name is given is Han Jin Gap, a character that only appears in one scene. The same goes for Texas Aunt. Even though we know Choon-mi’s name, she’s called Texas Aunt in the text. We don’t ever find out the name of the Woman from Kyrgyzstan, or her Korean stepdaughter. I think that’s fairly common in Korean playwriting, especially in plays that have a political bent. Many of the playwrights I’ve translated create characters that are more representatives of a certain social group than individuals. It’s common to see characters referred to by their occupation or role within the family, rather than given unique names. So, I’m interested to see you move away from that and focus more on the individual. One final question: is there something that you want international audiences to take away from your plays once they are translated?

Yun: It’s important for audiences abroad to understand the reality of Korean society, but I also want them to respond to the emotional lives of these characters. I want people to be able to put themselves in these characters’ shoes. I believe that’s what art is for. To feel with others.

Nahm: I’ll do my best to make sure that those feelings come across in the English translation. Thank you for speaking with me.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.