It was well past midnight on October 2, 2021. Current Plans—at the time known as Present Projects—had just opened its fifth group show, Fault Lines, and Hong Kong’s creatives lingered to philosophize over drinks. No one had the mind to leave. Instead, they decided to build a dolmen out of the yoga blocks that lined the gallery floor – a quirky, spontaneous effort that would pass as a creative endeavor to untrained eyes.

The blocks were part of South Ho’s playful installation, “Let the Bricks Fly a Moment Longer.” The artist was among the crowd, unfazed by the symbolic demolition of his work. In the coming days, these blocks would morph into sturdy castles for kids, a nap corner for fatigued workers, and many other things that curious viewers were free to explore.

Back at the midnight saga, a pragmatic few started helping the curator clean up, while others let conversations extend into the dawn. In its mere two years of operation, these amiable moments have come to define Current Plans, a collaborative, welcoming, independent art space in Sham Shui Po, run by curator Eunice Tsang.

Like many independent art spaces, it began life through a combination of coincidence and passion. Tsang had been working as a TV producer at RTHK, Hong Kong’s government-owned news network, when a friend told her about an art space in Sham Shui Po that was looking for curatorial proposals. “I jumped at the chance, as it had always been a dream to work with an off space,” says Tsang, referring to a term used to describe independent, curator-run art spaces. She had previously spent five years as an art writer and curatorial assistant at Tai Kwun, allowing many ideas for potential exhibitions to brew. But like many young curators in Hong Kong, these ideas remained unrealized in part due to the city’s notoriously high rent and lack of experimental spaces.

“Our Non-Understanding of Everything” by eteam, 2022, in “Witches Own Without.” PC: Current Plans

Tsang turned her ideas into a 30-page proposal, which impressed the space’s artistic partner, who turned out to be famed photographer Wing Shya. After a few months of communication, Tsang was brought on board in January 2021 by Shya and his partner, Cheryl Ng. “We shared a tight yet fluid vision of running the space in a generous manner, collaborating with creatives that cross boundaries, merging artists, video game designers, fashion designers and musicians together in exhibitions,” says Tsang.

Nestled on the first floor of a six-story tong lau, Current Plans is sandwiched between residential flats above and the Instagram-trending café Colour Brown below. There are two discreet entrances – a gated staircase leading to the street and a fancy green staircase in the middle of the cafe that connects the different floors of the building. When multiple signs were removed or relocated by neighbors who either objected to the art space or simply didn’t like its signage, Tsang realized that space-making would be a constant process of negotiation, not unlike the creative process itself.

In those early days, manpower was short, and the hours were harsh. Tsang’s small team consisted of her assistant, Sam Chan, a college student on a gap semester, and herself. She also credited her partner in art and life, designer Mario Bobbio, for his continuous dedication to producing a distinct visual identity for the space.

Chan (who uses they/them pronouns) recalls the beginning of the adventure fondly. “Those days were chaotic but fun,” they say. “Eunice and I were drilling walls at 2am and desperately trying to smooth wall text stickers. Commercial spaces can afford sifus who would come in with professional tools and knowledge. But for us, it was trial and error. Working with a tong lau space has its merits and shortcomings as well. In white cubes and art institutions, spaces are made for installation. But in a tong lau, you would find walls too moldy to drill or power sockets lacking where necessary. Building the place from scratch was a lot to learn.”

Fortunately, the art space had the support of the city’s creative community, who were drawn by its welcoming approach. “People would stop by to help just because they wanted to contribute their expertise to a shared space,” recalls Chan. Many exhibitions later, this community remains a strong pillar that supports Current Plans.

“Witch House Residency” by Ysabelle Cheung, 2022, in “Witches Own Without.” PC: Current Plans

The space’s first exhibition, in January 2021, was Natality, a collaboration between writer Chan Ho-lok, whose work deals with life, death, trauma and suffering with reference to the Christian and Buddhist views on the end of life, and painter Chan Bee, who transposes such discussions onto the female body, often presented in a mutated form in her works. That humble but intellectually ambitious show set the tone for the exhibitions that followed, which were defined by a cross-disciplinary nature and group-oriented focus that is less common in commercial galleries, because group shows are usually difficult to coordinate and slow to sell.

This has allowed for a layered interpretation of culturally-loaded themes. In the 2021 show Only A Joke Can Save Us, humor was examined through a rich body of works by nine artists. The show was grounded by a reference to George Orwell: “Every joke is a tiny revolution.” But a revolution against what? Mak Ying-tung explored the viewing public’s obsession with social media, Hui Rui looked at human negligence with regards to the climate crisis, Pow Martinez examined the politics of immigration and monarchy, and Fameme—a character created by artist Yu Cheng-ta—cast an eye towards the Covid-19 pandemic. Their vastly different works reflected a multi-faceted interpretation of humor.

Group shows like this allow for complexity, but the sheer number of exhibits and collaborators can be difficult to manage. More often than not, communication can be compromised amid a hectic installation schedule. To prevent this, Tsang puts extra effort into coordinating the installation process. “Current Plans can be an awkward space to install. It has low ceilings, a glass door, a kitchen, and a shop,” says Kay Mei Ling Beadman, who participated in Fault Lines with her 2021 work “Enmeshed.” But she praises Tsang for making the process as smooth as possible. “She gave us weeks to modify our works in response to the site. She also introduced fellow artists to allow for critical conversations,” she says. In Beadman’s case, she was put in touch with Yuk King-tan, whose work was being shown next to hers. “We made an effort to accommodate each other’s works for a better general navigating experience.”

Game designer Allison Yang also praises Tsang’s dedication to push creative boundaries. “In April 2021, I was about to finish The Forgetter, a video game in which players can experience the life of contemporary artists and destroy artworks,” she says. Tsang proposed curating an exhibition about this game and connected Yang and her creative partner Alan Kwan to two set designers, Nolan Lee and Emily Ho, who created a hyper-realistic space in Present Projects with the same aesthetic style as the game. Inside the room amid sand, mirrors, and bloody red branches representing neurolines—a way of visualizing neuronal connectivity that resembles a subway map—visitors huddled around a computer installed with the game, lost in their virtual adventure. Others became onlookers and commentators on the action.

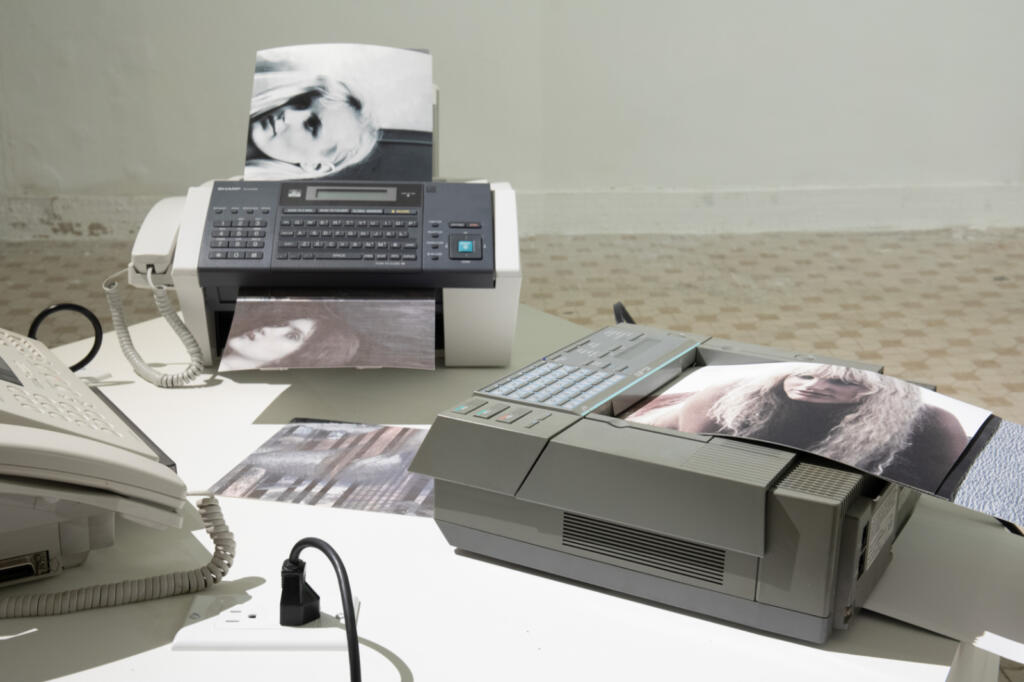

“Faxalka” by Christopher K Ho, 2022, “Witches Own Without.” PC: Current Plans

One year into its operation, the space had already made a name for itself among the city’s creatives, but the commitment of its initial patron was nearing its end. Fortunately, it had gained the trust of many supporters, veteran art collector Alan Lo being one of them. At the start of 2022, Present Projects became Current Plans, retaining Tsang as chief curator, with Lo as the major donor. Not long after, Sylvain Levy, co-founder of dslcollection, a major collection of Chinese contemporary art, confirmed sponsorship for the DSL Hub. It’s a room in Current Plans that focuses on pushing the conversation about digital art, like using VR and video games as a medium, to collaborate with more local artists and institutions who share the same interest in research, commissioning and developing such contemporary projects.

To reflect the changes, Current Plans secured collaborations with the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Lingnan University, which sent their students to complete internships under Tsang’s tutelage. This new infrastructure in turn supported more sustained programs, one of them being Game Kitchen, a biweekly event curated by Allison Yang. In large part an extension of her initial collaboration with the art space, Yang’s Game Kitchen comprises seminars, workshops, game-tasting nights and play-together gatherings featuring game artists and designers. Adding to its original art community, Current Plans now sees a vibrant ongoing dialogue about games, a form of art gaining importance in the contemporary art narrative.

For the first time since her adventure began, Tsang has found herself in a well-supported place for things to evolve. Now she is focused on opening her latest exhibition, Witches Own Without, co-curated by Ali Wong Kit Yi and Lok Wong, which is loosely focused on the renaissance of witchcraft in Hong Kong. Its curatorial text could be a commentary on Current Plans itself: “The title Witches Own Without deliberately appears to be an incomplete sentence, so as to allow anyone and everyone to complete it in their own way. But one possible way to complete it for today: witches own without possessing. Through collective ownership, we can own something without necessarily possessing it.”

Witches Own Without runs on weekends until November 6. Click here for more details.

The article was originally posted on Zolima Citymag on October 20, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mona Chu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.