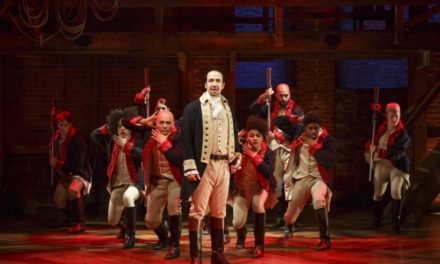

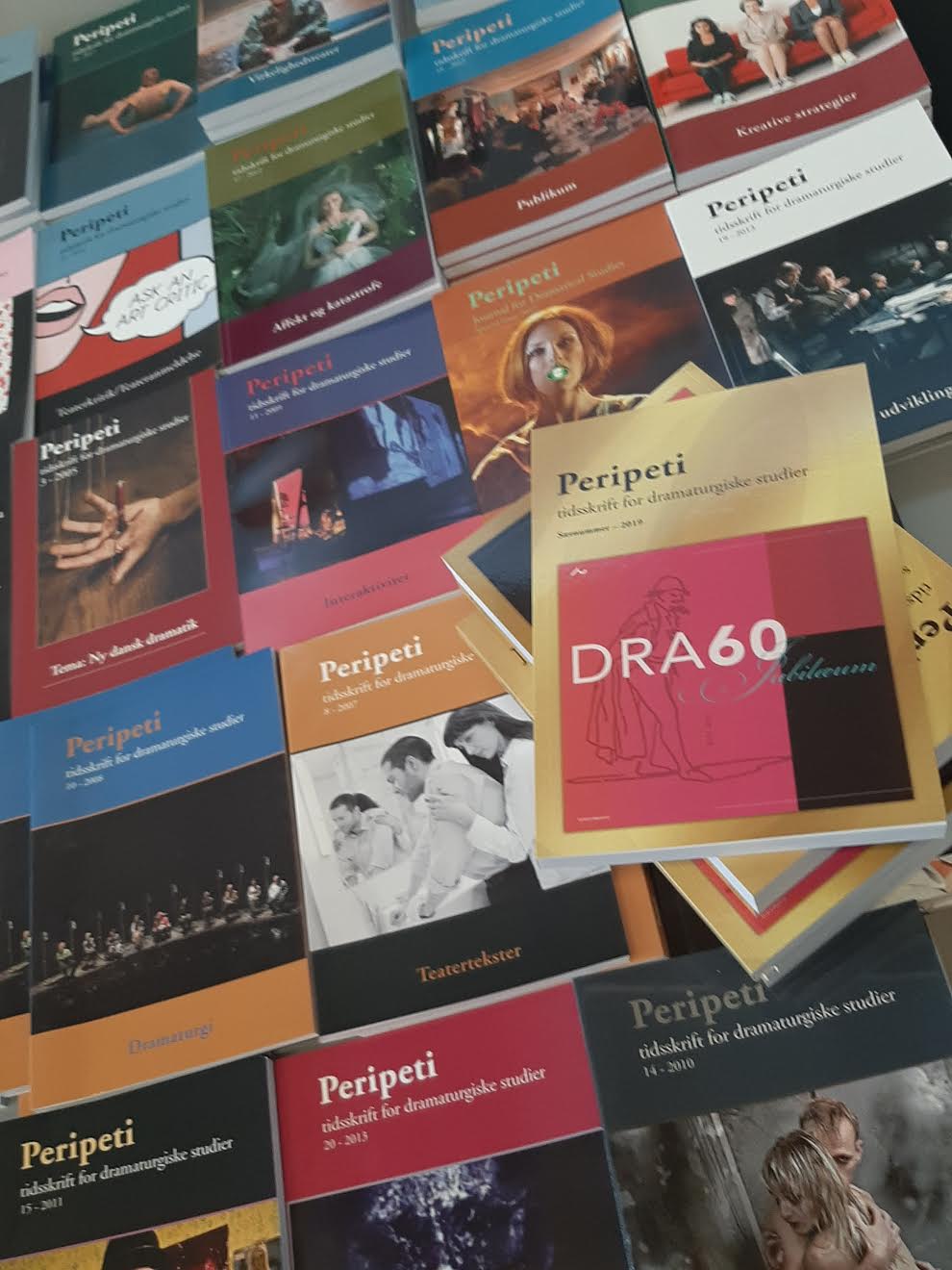

In The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy (2016), Magda Romanska argues that if the twentieth century can be called the century of the auteur-director, then the twenty-first century will be the century of the dramaturg. Of course, this builds on the assertion that the dramaturg’s field and role concerning theater production expands and takes on new forms. The dramaturg is no longer only aware of texts but is also involved in other forms of representation, as well as thinks of the use of space, the actions of the body, distances from and relations with the spectators. Based on Romanska’s claim, the organizers of the conference at Aarhus University asked: How does dramaturgy function as a concept and practice in Denmark today? What roles does dramaturgical work play in the performing arts? How is dramaturgy implied in the performing arts’ experiments with spectatorship? The one-day conference, held at Aarhus University on 21 September 2019, brought together a number of dramaturgs, actors, and directors to help elucidate and discuss these issues in a number of panel discussions. The conference was organized by the journal Peripeti– a dramaturgical magazine that endeavors to strengthen the connection between theatre research and performing arts – in collaboration with the Dramaturgy program at Aarhus University, the Association of Danish Dramaturgs, and the Danish National School of Performing Arts.

In Denmark it has been possible to study dramaturgical skills as an optional subject at Aarhus University since 1959, therefore the conference was also a celebration of the 60thanniversary of the study of dramaturgy in Denmark. In 1973 dramaturgy gained its own, independent department. Today the Department of Dramaturgy (joint with Musicology) educates around 35 Bachelor and 15 Masters dramaturgy students annually.

Kasernecenen at the Department of Dramaturgy, Aarhus University. Photographer: Morten Brockhoff.

The Century of the Dramaturg

Associate professor of Dramaturgy at the University of Aarhus, Janek Szatkowskiin his opening speech mentioned some of the works that have historically and currently unpacked and challenged dramaturgical theories and thinking. Within a Danish context, he drew a line from works such as Jens Kruse’s Det Følsomme Drama (Sensitive Drama) of 1934, and Tage Hind’s Dramaturgiske Studier (Dramaturgical Studies) from 1962, volumes which contributed to the establishment of a dramaturgical research tradition in Denmark, to Niels Lehmann’s Deconstruction and Dramaturgyof 1996, where the author argued for and practiced deconstruction as a dramaturgical strategy.

From the international field, a number of recent works on dramaturgy were mapped: Bert Cardullo-edited What is Dramaturgy (1995), Geoff Proehl’s Towards a Dramaturgical Sensibility (2008), Mary Luckhurst’s Dramaturgy: A Revolution in Theatre (2006), Cathy Turner and Synne Behrnt’s book Dramaturgy and performance (2008), and Peter Boenisch’s Directing Scenes and Senses (2015) were mentioned. Szatkowski highlighted the tendency to apply the concept of dramaturgy to different practices and contexts in a polyphonic theater landscape, where the role of the dramaturg also expands. As examples for this approach, he mentioned Roeder & Zehelein’s Die Kunst der Dramaturgie (2011), Katalin Trencsényi and Bernadette Cochrane-edited New Dramaturgy. International Perspectives on Theory and Practice (2014), Trencsényi’s Dramaturgy in the Making (2015) and Magda Romanska-edited The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy (2015). Another trend, which he gave attention to is the so-called ‘hyphenated theatre’: music-theatre, circus-theatre, dance-theatre, post-dramatic-theatre, performance-theatre. In addition to this, there is a renewed interest in immersive dramaturgies, which comes into view both in a sympathy for the effects of authenticity and activations through immersive theater forms and in an interest in new forms of dramatic realism. This, Szatkowski argued, can be seen in Bernd Stegemann’s critique of spectacular performances in favor of realism in his works: Kritik des Theaters (2013), Lob des Realismus (2015), and in Das Gespenst des Populismus. Ein Essay Zur Politichen Dramaturgie (2017). Gritt Uldall-Jessen is dramatist, dramaturg and curator, mainly working in the independent field of performing arts. She presented a dramaturgical view of action and activation theatre. Action theatre understood as direct intervention in a current social event, while, she explained, activating theatre as interventions that cause the audience to rethink their relationships to places and spaces. Inspired by Una Chaudhuri’s Land / Scape / Theater from 2002, Uldall-Jessen explained how in her work she is occupied in rethinking the anthropocentric by giving spectators new views of hybrids and nonhuman species such as animals, plants, and climatic change as phenomena, and by extension, she sees both action – and activation theater as political media. Jens Christian Lauenstein Led, dramaturg at Aalborg Theatre, positioned himself as a defender of the dramatic paradigm against the post-dramatic, which he challenged as too easy to commercialize, as he argued, “we risk losing the drama in favor of the spectacle,” just as the dramaturg risks becoming a ‘millennial artist’ who must solve all kinds of tasks in the post-dramatic paradigm. As an example of the spectacular, Lauenstein Led mentioned the large institutions’ theater concerts, which, he believes, wins a large audience by its scenographic equipment but fails by being more eye-catching than relating and involving. The tendency to present the immediate as citizens on stage and “reality theater” with authenticity effects were also included in Lauenstein Led’s criticism, which he rounded off by emphasizing his vision of the theater as the last place for long complex conversations.

Photo: Peter Boenisch.

Dramaturgy at The Danish National School of Performing Arts

Thomas Rosendal Nielsen, associate professor of Dramaturgy at the University of Aarhus, held a conversation with Mads Thygesen, principal of The Danish National School of Performing Arts. In Thygesen’s point of view, dramaturgy is primarily an analytical competence that can contribute to practice. For the same reason, dramaturgy can be applied to many processes in an expanding performing arts field, Thygesen claimed, and he described his managerial practice as dramaturgical management. Equally, The Danish National School of Performing Arts recently has changed its education program and is now focusing on educating performing artists for a broader market than they used to. Dramaturgy does not explicitly appear as a concept in educational programs. But as a new initiative, the school has been awarded a professorship in dramaturgy, which marks the importance of dramaturgical competence in their education. Finally, Thygesen stated that it is important for a performing arts school to see itself as part of the community, and therefore it is very important for the school to collaborate with the outside world, in non-artistic settings.

Experimenting with the Spectators’ Experience and Dramaturgy

Erik Exe Christoffersen, Associate Professor of Dramaturgy, University of Aarhus, discussed spectator involvement and dramaturgy in the performance of Audition, which played at Aarhus Theater in spring 2019. The artistic team, theater director Sargun Oshana, dramaturg Tine V. Ilum and stage manager Anne M. Basse, who worked very closely together throughout the performance process, then joined in the conversation. Oshana told how Audition was prompted by #MeToo, specifically how to give the spectator a physical experience of an assault. Oshana radicalized this by asking: “what if I was the one who committed the assault against the audience? Can I throw myself under the bus?” As a result, he, as director, played a small part in Audition as “the director”. Oshana stated that, while he, as director and performing artist was experimenting with his role and pushing himself ‘beyond the abyss’, the dramaturg “became the branches, you can grasp, when you are in free fall”.

The team’s idea was built on the belief that the theater as media can investigate and treat the abuse theme differently than other media, in which #MeToo has been subject to victim-blaming. They emphasized how important their work with audience tests during the rehearsal process has been, and seeing the audience as a dramaturgical parameter that they could adjust the performance to, were very important in the development of spectator positions. In this case, the director and stage manager had been present during each play-through, to make ongoing adjustments.

Sargun Oshana and Anne Plauborg in “Audition”. Aarhus Theatre, 2019.

The Dramaturgy of the Actor’s Physical Actions

Annelis Kuhlmann, Associate Professor of Dramaturgy introduced actor, writer, and festival organizer, Julia Varley, who has been a part of Odin Theater since 1976. Varley presented her work, The Dead Brother, and demonstrated how the actor’s creative process works in Odin Theater’s dramaturgical form. In the introduction, Kuhlmann described the above work demonstration as a small performance that, in an aesthetically-documentary form, opens some of the actor’s considerations that arise in the process of creating personal work. The Dead Brother illustrates how performances often turn out at the Odin Theater. One could say that its dramaturgy reflects its materiality and technique and presents different stages in a process in which text, actor, and director interact. In theater anthropology, the word ‘subtext’ has been replaced by ‘sub-score’ in an effort to avoid focusing primarily on a text-based theater form. The term sub-score involves all mental and psychological processes on which the actor bases their work. There are also personal techniques that help keep the sub-score alive across the actor’s motives, inner world, emotions, energy, memories, etc. The demonstration was followed by a brief conversation about the scenic presence between Varley and Kuhlmann. Here, Varley articulated that her dramaturgy is incorporated into the body: a ‘dramaturgy in the feet’.

Dramaturgy in “Outskirts Denmark” – The Village Laboratory in Idom

Louise Ejgod Hansen, Associate Professor of Dramaturgy, introduced the Village Laboratory as an example of a local dramaturgical, artistic, and cultural practice outside the institution’s framework. The village laboratory was started by Kai Bredholdt and Per Kap Bech Jensen, who both work at the Odin Theater, but live in the village of Idom, as do Erika Bredholt, a Mexican flamenco dancer, and Nikolaj Rosengreen, a guitarist, who are all part of the village laboratory’s core. Ejgod told of a village performance of Hamlet in a coliseum built of straw bales. The performance included two Norwegian new circus players, and Hamlet’s father’s ghost was played by a rabbit. In 2019 Idom was named village of the year in the Central Jutland region. In this respect, the chairman of the Idom Citizens’ Association, Dennis Thiesen, stated: “The skewed ideas, the border-searching events have become part of the village’s DNA, which we are proud of.” Per Kap Bech Jensen inaugurated in the village laboratory’s 10-year plan for an experiment with the citizens of the city. Every two years, a village biennial is held. Here they do not recruit people by asking if they want to play theater, but instead invite them by asking: “What are you the best at?” – be it riding a tractor or a horse. Running the biennial with the villagers of Idom requires being able to create a dramaturgy out of the given materials, plus large quantities of good coffee! – Beck Jensen concluded while Kai Bredholt, Nikolaj Rosengreen, and Erika Bredholt sang, played, and danced flamenco.

Immersive Dramaturgies

Ida Krøgholt, Associate Professor of Dramaturgy, chaired a conversation with Sara Topsøe-Jensen, who is an instructor, scenographer, and manager of Carte Blanche, a regional theatre in Viborg and Josefine Brink Siem, a Ph.D. student in Dramaturgy at Aarhus University, who works with affective dramaturgies. Krøgholt introduced the concept of immersion, which is known from the computer game world when the player dives into the game and forgets everything around them; and from virtual reality where the spectator is surrounded by the medium. In the art world, ‘the immersive’ is generally used about the immersive dimension of art experience, but it is also used for a particular kind of work. Theater researcher Josephine Machon described immersive theatre as experience spaces that immerse the spectator in an imaginary universe, and where the spectators get the agency to respond with their physical bodies in the universe, that can be experienced as “uniquely for me.” Sara Topsøe-Jensen told about Carte Blanche’s experiments with immersive experience spaces coupled with the idea of creating encounters between people. She recounted the theater’s meeting with Greek-Cypriot refugees in Cyprus, where performers and participants together explored the meaning of the concept of hope, seeking beauty and meaning in a context where it is difficult to find. Libraries have also served as settings for staged atmospheres. Topsøe-Jensen explained why she as a director has no interest in constructing a fictional level but works with an atmospheric aesthetic, and with performers who create a sensory experience for the audience, who are allowed to taste, feel, listen, smell or ask questions during the experience.

In the Danish theatre landscape, there are several ways of working with the immersive experience. Siem addressed the question from a more general, theoretical vantage point, and talked about a schism between poetic and ethical dramaturgies. Poetic dramaturgies’ way of building sensible spectatorship can be observed in the works of Danish theatre groups: Carte Blanche, Wunderland, Secret Hotel, Cantabile2. Here the dramaturgy draws the spectator towards a wondering perspective in a holistic and all-inclusive context. On the other hand, ethical dramaturgies such as the projects of Signa, test the spectators’ personal values in more antagonistic forms by confronting them with difficult choices of actions. In conclusion, Siem discussed what the immersive can be a response to in art and society, and whether immersive theater can be seen as a dimension of the spectacular post-dramatic paradigm, as Lauenstein Led noted earlier at the conference.

Photo: Peter Boenisch.

The Current Status of the Concept of Dramaturgy – Towards Ecological Practices

The conference talks were briefly summarized and commented on by Thomas Rosendal Nielsen and Cecilie Ullerup Schmidt, performer and Ph.D. fellow at the University of Copenhagen.

What is the status of the concept of dramaturgy? From primarily dealing with text, it has spread to a globalized and differentiated field. What are the tasks and challenges of dramaturgy in this broad field of issues?

Rosendal Nielsen observed how the conference revolved around two positions, both based on the social involvement of art. On the one hand, there is the performing arts activism where dramaturgy refers to organizing, intervening, disrupting societal relationships. A wide globalized field was pointed at; for example, this can be observed in international collaborations. On the other hand, there is a more focused dramaturgy, which prioritizes ways of telling stories and developing a new approach to realism concerning dramas dealing with real-life conflicts.

The importance of dramaturgy in a complex collaborating field also emerged in connection with the performance Audition. In this case, the dramaturg does not simply analyze the text and the audiences’ potential response – due to the complexity of the dramaturgy, the dramaturg became an indispensable part of the artistic team.

Odin Theater demonstrated a dramaturgy that is based on the relation to the body as life and energy, and it is the actor’s task of shaping this life and thus creating a scenic presence. But also, in a broader sense, life is created in the village of Idom with many examples of theatrical relationships between what the residents are good at and what actions and materials the dramaturgy bring to life.

The last note debated immersive theater as both analogous and different from the experience economy. Dramaturgy is aimed here both at inner and outer life – the sensory and the ethical with an awareness of the risk of ending up in the spectacular, and with an interest in seeing what is beyond the many fictions in which we interact daily, according to Sara Topsøe-Jensen.

Ullerup Schmidt found it important to avoid competition between the functions and roles of the theater. She called for a view that sees dramaturgy from an ecological perspective, which rises beyond the fact that dramaturgy theories are mostly written by men, except for the female anthologies of recent years. Can dramaturgy be thought of in a different way than a practice that takes place invisibly in the dark? Isn’t the role of dramaturgy also a supportive and relationship-building practice? Often the dramaturg is presented as a figure between functions and projects. The dramaturg can contribute to the text as co-author, curator, analyst, director’s assistant and even as production manager, yet is often the first person to be cut off when the production is growing in scale or financially, and is rarely mentioned in programs or credited for the dramaturgical work.

Is it possible to make visible the invisible ecological practices of performing arts as a practice of care?

This was one of the issues that were strongly stressed after the conferences meeting of artists and academics.

Ida Krøgholt is an associate professor (Ph.D. in Dramaturgy) at Aarhus University, Denmark. Her research area is performative forms, participatory theater and applied theatre and theater and drama in education. She has been an associate researcher in several projects, most recently in ‘Not just for fun’, Aarhus Theater (2015-2021). Her most recent publication: Revitalizing Drama in Education through Fictionalization – a performative approach (with Knudsen, Kristian Nødtvedt) in Performative Approaches in Arts Education. Anna Lena Østern; Kristian Nødtvedt Knudsen. Routledge, 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ida Krøgholt.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.