Ninasam Tirugata staged two plays –– Kalandugeya Kathe and Atta Dari Itta Puli. One reads the contemporary into classical, and the other bares the present itself.

Ninasam Tirugata’s play Kalundugeya Kathe directed by Venkataramana Aithal, repeatedly breaks the notion of time, for its own self and for its audience. The play, though based on the Tamil epic Silappadikaram, becomes “kathe” (story) and not “mahakavya” (epic) in its theatre text. In its very choice of name, the play gets off its classical pedestal, hinting that it has contemporary concerns at its core. The play looks and employs the classical, but through its dynamics and technique, it displaces space and time that this second century text is set in. The storytellers who double as characters within the play, enter the world of Kannagi and Kovalan, but also exit from it every now and then to have a conversation with the mela, the musicians. This “breaking away” that keeps repeating itself, works like a code for something that is to come: Aithal uses this technique brilliantly for an effect that is a two pronged treatment of time, and hence multiple.

The performance text is a combination of three plays by renowned poet and playwright H.S. Shivaprakash — Madure Kanda, Madhavi and Matruka based on the Tamil epic. Central to the play is the love of these two extraordinary women, Kannagi and Madhavi for Kovalan, which infuses the play with tender and passionate moments, as also passages of separation. However, the play takes a huge leap with the kind of choices Madhavi exercises. The daughter of a dancer, she rebels against the system that she is born into and remains steadfastly loyal in her love for Kovalan. As the play transits through love and longing, the location of the story also changes. While change in geographical location marks the various stages of the relationship of Kannagi-Kovalan-Madhavi, it also reflects the movement in the inner landscape of these individuals. The stunning mirror scene in a way, is crucial in this direction. The mirror carries the reflection of Kannagi and Madhavi, who while celebrating their beauty, see a fleeting image of Kovalan. This, as Aithal sees it perhaps, is the moment of Abhijnana, the beginning of the journey of self realization for the women. These small moments of self realisation, as the play records, eventually leads to a larger social change. Ironically, this journey to victory is marked with personal pain, loss and suffering. Both Bindu and Roopa as Kannagi and Madhavi, play their roles with exceptional conviction. The performance text, it is clear, reads it as the story of the woman and not merely a love story. It gives voice to the woman, a marginalized entity in a larger patriarchal order. Madhavi is a rebel within her community, and Kannagi, clearly a meek product of patriarchy, takes on the system with anger. Until then, Kannagi who does not ask questions of justice within her relationship, poses them to the establishment and even defeats it. Manimekhalai, the daughter of Madhavi and Kovalan, moves out of the folds of Jainism, and becomes a Buddhist. The women therefore break away from their own selves: also, from time. They defy the time that they are set in, they also transcend their time by becoming powerful symbols of hope and defiance for those who live on the edges. The male order which upholds the values of the docile wife Kannagi, paradoxically accepts her new avatar and canonises her as Devi. It is clearly a play that demolishes social and literary stereotypes.

However, all these strengths become fragmented experiences due to the play’s length. In a taut script these happenings could have been more intense. Like a piece of poetry, it opens up to its meanings in recollections, and thereby disappoints as drama. The use of Purandara Dasa’s “Yaarige Yaaruntu” and Akka’s vachana “Naanondu Kanasa Kande” seemed philosophically heavy for the play trying to make over stretched connections. Considering the intensive musical element, the team could have done better with good singers. Set design, and lighting were of a high order.

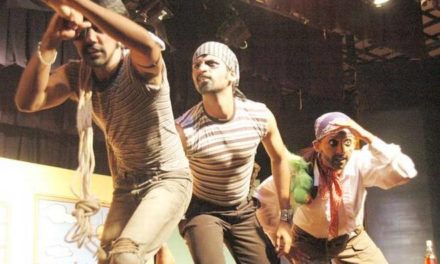

Atta Dari Itta Puli, directed by Heisnam Tomba, is a personal account of life in Manipur. Son of the legendary theatreperson Kanhailal, Tomba’s script depicts the atrocities of Indian Army in the North East, which has instilled everyday life of the common man with terror and violence.

The play, which bears reminiscences to his earlier play Hasida Kallugalu, is highly stylized and visually haunting. Clearly, Tomba is influenced by his father’s method of reconditioning through the body of the performer. In its pace and intensity it creates the effect of Sankaran Venkateshwaran’s Water Station. The exacting body language, unsettling gestures and shrill, piercing music, throw difficult questions at you. It questions the very idea of nation state, it also asks you to answer humanitarian questions. What would you have done if your son, father, husband is shot at whim? What would you do if your wives, daughters and mothers are raped with a beastly instinct? Surprisingly, in a narrative such as this, Irom Sharmila is missing.

Most of what formed the 80 minute play was newspaper reports and its enactment, what stems from the belief that theatre is social action. Much like the street play form, the play did resort to sloganeering. But in a play of such nature, artistic debates beyond a point appear as heartless indulgence.

While the two Tirugata plays that have just begun their rounds may not be the best that has come out of Ninasam, one cannot take away the fact that the performances were stellar. The rigour, discipline and professionalism of the actors is unmatched. What is more is the vision that they take forward: the Tirugata actors travel to the nook and corner of Karnataka carrying the beliefs and ideals of an institution like Ninasam. In this day and age, when material aspirations rule, the choice that the Tirugata actors have made deserves a standing ovation. They add themselves to the rich legacy that the earlier editions have left behind.

This article was originally published on the Hindu.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Deepa Ganesh.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.