In the airy sitting room of a nice house, a group of friends are catching up over a glass of wine. “So what have you been up to lately?” says one. “Me? Oh I’ve been raping pensioners,” replies another.

This is Consent, a white-hot new play by Nina Raine, which opened to critics at the National Theatre on Tuesday 4 April. Its subjects are not, as the above conversation might suggest, psychopathically hardened criminals, but barristers. Raine discovered their peculiarly offhand way of speaking over the course of a research lunch in an “unglamorous, threadbare” courthouse canteen.

“They do it as a shorthand, specifically with other barristers. Rather than saying, ‘I’m defending this man who is accused of… ,’ they say, ‘We raped blah blah blah’. Then you get all of the details of the case without the circumlocution. They do it with a very light touch – it’s not self-conscious.”

Consent is, as the title suggests, a play about rape. There is a central case – about a young woman who is attacked on the night of her sister’s funeral – on which two of the leading characters, Edward (played by Apple Tree Yard’s Ben Chaplin) and Tim (Pip Carter) take opposing briefs.

While what happens to the young woman is at the heart of the play, Raine’s main focus is on the domestic lives of the lawyers – their marriages, children, friendships and, in time, their affairs, arguments and legal battles. It is a courtroom drama where most of the drama is outside the courtroom.

“I’ve never seen Twelve Angry Men,” says Raine. “I didn’t want people to say, ‘Oh, it’s another courtroom drama.’ And I didn’t want to just write a play about rape. It’s such a dark, layered subject. I wanted to write a play in which there were two very different rapes. To ask those questions: can there be different kinds of rape? Is rape always rape?”

It is potentially explosive subject matter. “I hope it’s provocative, that it makes people think about themselves as people as opposed to the legal niceties of this or that,” says Roger Michell, who is directing. “I hope we get into trouble.”

“Oh my god, I don’t,” says Raine.

The title refers to the pivotal crime but also to the relationships of the protagonists. “It’s also about what you consent to in your marriage,” she says. “Do you consent to your partner cheating on you, tacitly? Or there’s a thing called duress – you consent but you’re forced into it. How much is that really consent?”

Is Jake (Adam James) really having an affair, or is his wife Rachel (Priyanga Burford) over-reacting? When does infidelity start? Does Ed fancy Zara (Daisy Haggard) or is Tim just cross-examining him about it for the hell of it? Does Ed bring his troubles on himself? Do two wrongs make a right? What is justice?

The audience is invited to sit as the jury on all these questions, listen to the various characters’ truths and weigh up the evidence.

“The interest is in the greyness, in the fog,” says Raine. “If it was all black and white, why would it be interesting to watch? What I wanted to write was something where there were two truths and they both believe them.”

“I think it would be best if people come out of the play not being quite sure of the exact nature and provenance of the incidents,” agrees Michell, who previously directed Raine’s 2010 play, Tribes.

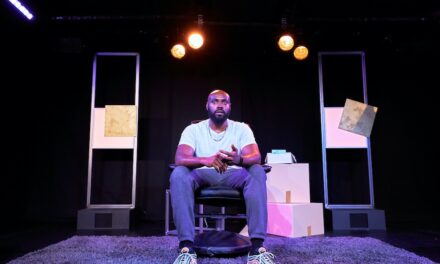

Consent a new play by Nina Raine, directed by Roger Michell at the National Thatre. Photo: Mary Parker

To add a small frisson to proceedings, his wife Anna Maxwell Martin stars as Edward’s wife Kitty. Has it been a tricky play to work on together? “It’s been better than normal,” says Michell. “In the past I’ve found it very unnerving trying to direct her because she’s so badly behaved in rehearsals, always cackling and making jokes.”

Consent is a natural successor to Raine’s 2011 play, Tiger Country, about the lives of NHS workers in a busy hospital; it concealed a righteous anger about an under-funded and over-stretched institution beneath the everyday dramas of the characters.

This time, Raine was inspired by the details of a real-life sexual assault case, in which the fragile mental health of the complainant was cited in court, but the fact that the defendant was on bail for a violent crime was not. “I thought it was so unfair,” she says. “And it feels more unfair because the court is being so scrupulously fair to the man.”

This is not, however, a play with a message. “It would be misleading if people came to it expecting to see a series of metaphorical placards being waved in their face, saying rape is wrong,” says Michell. “Of course we know that rape is wrong. It’s a much more complex account. It’s about the bad interface between human behaviour and the law.”

It is also about the effect that a job which forces someone to see the worst of human nature – day in, day out – might have on their psyche. “How it twists or contorts the way you see the world,” adds Michell.

The play suggests that constantly having to pick a side and construct a plausible truth might be to the detriment of each barrister’s moral compass. As the play develops and their personal lives start to fall apart, our sympathies shift at an alarming rate.

“They are humans,” says Raine. “I always seem to write these plays where people say, ‘Oh my God, they behave so badly – they’re so dreadful.’ I don’t really know how to write any other way. I can’t write just good people. I can’t think how that would be dramatic.”

A vein of the darkest comedy also runs, unexpectedly, through the play. “It’s funny when people behave badly. It’s interesting and it gives people something to debate. The question is, can you have people behave badly and keep sympathy with them? I hope you do.”

Michell and Raine visited a court in London to get a feel for the realities of the profession. “I was very mindful that we all think we know about courtrooms from Rumpole, or Charles Laughton in Witness for the Prosecution,” says Michell. “And of course that’s all bollocks.

“Real courts are banal, uncharismatic, quiet, horrible modern buildings with low ceilings and no windows. The barristers look scruffy and bored. It’s shockingly banal. It’s not people making impassioned speeches and throwing their wig around. It’s people wading through huge bundles of grey documents and witnesses clearly bored in the dock. It’s much odder than what we think courtrooms are like, which are places of high drama, queeny performance, of people flourishing their glasses and all that frippery. It doesn’t happen.”

Similarly, the lead characters go against the barrister stereotype: “We imagine that barristers are a) posh, b) rich, c) arrogant – and they’re not like that at all,” says Michell. “In the play, they’re much more diverse than that; they’re actively not like Rumpole.”

Raine has been writing the play – between directing jobs, and giving birth to her first child – for seven years, since she was commissioned by Max Stafford Clark and Out of Joint. It arrives on stage at a time when rape has been the central theme of several high-profile dramas Apple Tree Yard, Broadchurch and the Oscar-nominated Elle. Is it a coincidence that the subject matter is suddenly everywhere?

Raine suggests that high-profile cases such as Jimmy Savile and Ched Evans mean that the question of how complainants and defendants are treated by the law is currently in the ether. “It might also have to do with Twitter and trolling and the way that rape is being used as a threat much more now,” she says. “The debate is out there much more.”

Certainly, the National Theatre is tapping into a live issue with the play. “It’s not an issue play,” argues Michell. “I think that demeans it. It’s a brilliantly complex modern play by a modern playwright. That’s why the National should be doing it. Not because it’s a campaigning play. “If [the audience] go out thinking, ‘Did he? Did she? Who’s in the right?’– that’s exactly what I want.”

Consent, National Theatre, London, in rep to 17 May (020 7452 3000)

This article was initially posted on inews.co.uk. Reposted with permission. To read original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alice Jones.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.