Christina Papagiannouli directs and devises cyberformances on online platforms such as UpStage and Waterwheel Tap. She is a research assistant and lecturer at the University of South Wales, and her monograph Political Cyberformance: The Etheatre Project was published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2015.

Christina, could you please start us off by describing some of your own cyberformance projects? What was political about them?

I directed my first cyberformance—the genre of digital performance that uses the Internet as a performance space—in 2011 for my practice-based PhD research, The Etheatre Project: Directing Political Cyberformance. The project comprised a series of experimental cyberformances that aimed to explore the political and interactive potentials of online theatre, under the umbrella of Bertolt Brecht’s directing methodologies and theories.

Cyberian Chalk Circle, an online, interactive, chat-based adaptation of Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle was performed in 2011 on UpStage, and the following year on Waterwheel Tap. In Cyberian Chalk Circle, Grusha’s story was placed in Egypt in 2011. The political power of the Internet was well demonstrated in Egypt’s cyber blackout during the 2011 public unrest, when the government cut off the entire country from the Internet, shortly after blocking Twitter, Facebook, Google and YouTube. The audience engaged with the Egyptian revolution by making correlations with their own reality. This allowed for different opinions to be exposed during the performance, shaping debates on sociopolitical themes.

In Merry Crisis and a Happy New Fear (2012), audience members replied to questions in a questionnaire during the performance, taking active part in the co-creation of a real-time verbatim cyberformance in which they became both the performers and the witnesses to what was happening. The questionnaire aimed to collect individual memories to create a performance about the collective memory of the unjust murder of a 15-year-old student by policeman Epaminondas Korkoneas in 2008 in Greece.

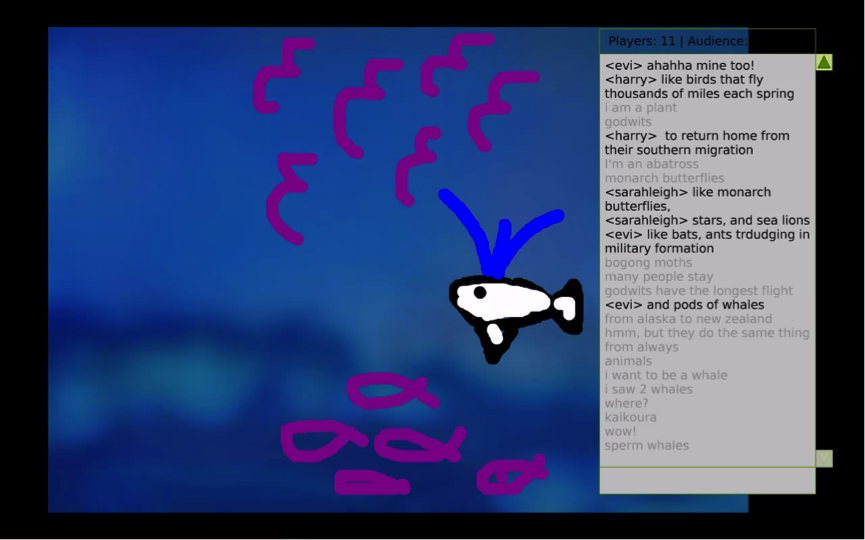

In Etheatre Project and Collaborators, I collaborated remotely with international artists and cyberformance experts to stage a cyberformance about migration, immigration and emigration on UpStage for the platform’s 10th birthday celebrations in 2014. The piece was based on the personal, individual stories of the collaborators who were all migrants themselves, living and working outside their home countries. During the performance, the audience became part of the collective ensemble, sharing their personal stories alongside those shared by the collaborators.

All three projects invited the audience into the creative process, turning the Internet into a collective space for real-time collaboration, engagement, and exchange. Due to the interactive character of the pieces, the audience completed the performance text in real-time, offering a critical response to the sociopolitical themes of the performances.

Why do you prefer the term “cyberformance” for such projects over other denominations such as “digital theater,” “virtual theater,” or “online performance”? Do these various terms describe different practices and approaches?

“Cyberformance,” “Cyber(-)theatre,” “telematics performance,” “cybertheater(s),” “digital practices,” “hyperformance,” “networked performance,” “cyberdrama” … There is a great range of terms trying to describe the phenomenon of online theatre. On some level, this shows the lack of agreement on terminology between scholars, researchers, and artists. I almost made the mistake to add my own term, Etheatre, in this long chain when I started my research back in 2010. But instead, I decided to re-use Helen Varley Jamieson’s term “cyberformance,” as it has been well defined in Jamieson’s research and in the work of others, including Maria X and Unterman. However, the terms do describe, or could be used to describe different practices. In the book’s preface I bring the different terms into discussion in an attempt to categorize their meanings and uses. One example is that “telematic performance” (use of streaming and video conferencing applications) and “hyperformance” (use of hypertext) can be considered to be subcategories of “cyberformance” (use of the Internet), which in turn can be seen as a subcategory of the umbrella term “digital performance.” Overall, I prefer the term “online theatre” set in a binary relationship to “offline theatre.” I think “online theatre” clearly describes what I do: I direct theatre online.

In your book, you also discuss works by artists and groups ranging from Forced Entertainment to Rimini Protokoll. How do you relate their work to your own?

In the book I analyze a range of online works, including productions by the National Theatre Wales, NTLive, Dries Verhoeven, Forced Entertainment, Rimini Protokoll, Merton and Ben Folds, Annie Abrahams, Helen Varley Jamieson, Field Broadcast and others to locate The Etheatre Project in a lineage of practice. Most of those productions took place alongside the practical exploration of The Etheatre Project, inspiring and informing my work as a cyberformance director and researcher.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of doing online theatre versus live performance, especially in terms of political efficacy?

Advantages: anonymity, audience interaction, allows the audience to be heard via the chat-box, gives tools for creating identities, connects distant people, offers free-of-charge platforms and tools. Among the disadvantages I would add here the issue of surveillance. Although the Internet is a democratic medium, it has been used for undemocratic and surveillance purposes. Moreover, new technology quickly becomes old. This requires constant updates and building new platforms to cope with the quick spread of technological changes.

What’s your take on arguments invoking notions of “liveness” and “presence” to deem online performance practice as somewhat inferior to “live theater”?

Bertolt Brecht defines theatre as a “live representation” of human interactions with an emphasis on entertainment, highlighting the importance of liveness in the theatre. The presence of a live audience relationship is central to the definition of theatre. But I define “live” as any kind of performance that is not pre-recorded for its audience. So despite the delay that may occur during online communications, cyberformance is a live performance owing to its real-time character. Although performers and audiences are geographically dispersed, they share a common space, the cyberspace. Text-based communication and interaction is crucial in cyberformance in terms of co-presence, not only for the audience but also for the performers. Like for the classic theatre experience, the presence of an audience is fundamental for the “magic” of online theatre.

Are you excited about any new directions in digital performance you’ve been noticing lately?

There is a rise of streaming theatre performances live to online audiences, but these performances cannot be described as cyberformances, since online audiences are only witnesses to the offline event, rather than participants in an online performance. What really excites me, though, are the new possibilities gaming technologies offer to cyberformance. Pokémon GO, for instance, has managed to build a new kind of audience interaction, changing the way we interact with our phones and our surroundings—the parks are suddenly occupied by young people and the whole world has turned into a treasure-hunt game. This opens new possibilities for digital performance, not because what it does is new—we’ve seen already similar uses of mobile phones and the Internet in performances by Blast Theory—but rather because it builds and trains a new kind of audience for such types of digital entertainment.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ilinca Todoruţ.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.