Wellington, a portside city famed for its turbulent seas and hurricane-force winds, turned on a miraculously calm evening for the spectacular outdoor performance event Kupe which opened the 2018 New Zealand Festival on Friday, February 23. Only a few days before, the city had been lashed by ex-tropical cyclone Gita, causing flooding and road closures throughout central New Zealand, and fuelling speculation on the streets that the great ocean-going waka (canoes) that were the centerpiece of the show might not be able to reach Wellington.

Kupe is acknowledged as the first Polynesian navigator to reach the shores of Aotearoa/New Zealand almost one thousand years ago. The production, co-created by director Anna Marbrook, navigator/waka expert Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr and designer Kasia Pol, re-enacted the arrival of Kupe’s waka fleet in Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington) several centuries before Captain James Cook’s Endeavour mapped its way around the coastline. Four double-hulled waka sailed from Samoa and other parts of Aotearoa to take part in the performance, which used Wellington’s dramatic harbor as scenography.

The crowds gathered early, fringing the entire length of the Wellington wharves, mirrored by a flotilla of spectator craft stretching from Clyde Quay wharf to the ferry terminal. By 6.30 pm an estimated twenty thousand spectators had squeezed into every available space, standing, reclining on picnic rugs, or sitting with their legs dangling over the edge of the wharf. Children pushed to the front, people made space for an elderly British tourist who needed to sit down, lifesaving crews in small boats circled watchfully.

The performance was perfectly timed to coincide with the sunset. Wellington harbor formed a natural amphitheater, with distant mountains far upstage, the jagged hills of the Wellington faultline to stage right, the sculptural form of the national museum Te Papa at stage left. The city’s highrises loomed like oversized scenic flats, giant speakers stood like silent monoliths, and the ocean was center stage. As we waited for the show to begin, the regular harbor activity became mise en scène. An interisland ferry lazily approached its berth, processions of trucks and cars drove along the Hutt Road, a 747 banked its way towards its flight path.

Kuramarotini (Maisey Rika) calls across the harbor to her husband in Kupe New Zealand festival 2018. Photo credit: David O’Donnell

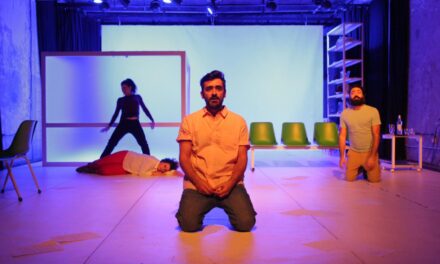

The crowd hushed as a haunting chorus of native birdsong rose on the speakers. This gradually transformed into monumental music, composed by Warren Maxwell, whose illustrious career includes founding the influential bands Trinity Roots and Little Bushman. At stage right, on a massive platform resembling a high diving board, with a waterfall cascading from it, Kupe appeared, dressed in stylized blue robes. As played by Te Kohe Tuhaka, he had the mana to command the entire city. Opposite him across the water, in front of Te Papa, his wife Kuramarotini (Maisey Rika) appeared on another platform dressed in red, the visual impact dilated by a magnificent drop of red fabric flowing from the platform. Their amplified voices echoed and intermingled across the water as they narrated their story. Then women began chanting a haunting karanga (summoning call) in te reo Māori (Māori language). Drones hovered above the performers, filming close-ups which were simultaneously projected on large screens strategically spread throughout the crowd so that everyone could get a good view (some also watched it online on their iPads). The miracles of modern sound systems made most of this perfectly audible, with the haunting call seeming to echo around the surrounding hills.

The waka Haunui circles the harbor in Kupe. New Zealand festival 2018. Photo credit: David O’Donnell

First, a war canoe emerged, sluicing through the calm waters, energetically rowed by a crew infused with the ihi (essential force) of the event. Then, one by one the much larger double-hulled waka appeared, gliding past the appreciative crowd who applauded every one. Their arrival was accompanied by Maxwell’s compositions performed by a massed choir on a raised stage in front of Te Papa, many of whom were dressed in various riffs on traditional Polynesian clothing. Maxwell’s complex blend of indigenous and contemporary music styles contributed to the joyous eclecticism of the event. The waka gathered upstage and dropped anchor to rest. A golden geometric vessel appeared in the distance, a stylized interpretation of the star that guided Kupe to Aotearoa, sailing through the other boats towards us. A woman in white robes stood atop the star, addressing us with a poetic monologue in English. Her words “When you know where you are, you know who you are” summed up the themes of the show, bringing together a sense of place and cultural identity against the setting of this powerful layered imagery where the passing jets and hovering drones were as much a part of the story as the visiting waka. A thrilling haka (rhythmic dance) specially composed for the event, was performed by a 1,000 strong group lined up along one section of the wharf. Finally, dozens of kayakers sculled into the foreground, adding a contemporary layer to the scores of vessels now filling the ocean before us. The mountains turned a soft grey with the pink hue of dusk framing the entire image.

The star waka approaches Kupe’s fleet of voyaging canoes in Kupe, New Zealand festival 2018. Photo credit David O’Donnell

Kupe was arguably one of the most spectacular pieces of theatre ever performed in Aotearoa, turning the entire harbor and city into a stage, evoking the mythic past as well as the bustling activity of a twenty-first-century city which is a hub for migration, business and the center of government. In a series of stunning tableaus, Marbrook, Barclay-Kerr, and Pol brought past, present, and future together in a celebration of voyaging and of Aoteroa’s legacy as a migrant nation. The participation of thousands of performers, and close collaboration with local Māori elders made this an inclusive event that reinforces partnerships between tangata whenua (indigenous people) and tauiwi (those coming from afar).

Kupe was the first part of a five-day sequence of events collectively entitled Waka Odyssey, which includes a comprehensive online presence on the New Zealand festival‘s website. The day after experiencing Kupe, I attended Ka Tito Au: Kupe’s Heroic Journey, a solo play by Apirana Taylor based on Kupe’s pursuit of a giant octopus that brought him to Aotearoa, then joined thousands of more spectators gathered on the Petone foreshore (10 kilometres from the CBD) to witness the waka arriving on the same beach where Kupe made landfall. I witnessed a moving ceremony as local dignitaries provided an emotional welcome at the water’s edge for the waka which had journeyed all the way from Samoa.

Diana Looser has written about the ways in which the performing arts have contributed to the renaissance of interest in indigenous seafaring and navigation in Oceania, demonstrating that such performances go “beyond voyaging to address socio-political and aesthetic issues of belonging, affiliation, identification, and agency in the Pacific.” (“Oceanic Imaginaries And Waterworlds: Vaka Moana On The Sea And Stage,” Theatre Journal 67: 3, 2015, 486). Kupe is a worthy addition to this wider project, a wildly ambitious piece of site-specific community theatre that draws attention to the ways in which the sea has been a vital space for the staging of history. It foregrounds the achievements of the Polynesian sailors who navigated by the stars and voyaged throughout the Pacific for centuries prior to European colonization. The weaving of a grand-scale mise en scène with narrative, music, and movement goes far beyond re-enactment to create dialogues between past, present, and future, opening up questions of Aotearoa’s kinship with the Pacific Islands, and foregrounding its Polynesian legacy and identity. As Aotearoa welcomes new waves of migrants and refugees from around the globe, Waka Odyssey is a timely and optimistic recognition of the intercultural diversity of a South Pacific country with a dynamic history of migration and voyaging looking to the future.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David O'Donnell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.