In the world of piano, J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations is a siren’s call.

Countless pianists have fallen prey to the Goldberg spell, many to the point of lifelong obsession. Originally intended for the two-keyboard harpsichord, the work is a real technical challenge to master, involving a dizzying number of hand-crossing acrobatics. Centered around a single bass theme and set primarily in G major, the thirty variations essentially follow the same sequence of harmonies–requiring a true sense of artistic interpretation to avoid sounding monotonous. In other words, even with a flawless execution, there is still the very real danger of simply boring the audience.

As American classical pianist, Jeremy Denk, explains, “The Goldbergs are a fool’s errand attempted by the greatest genius of all time.” Yet, the Goldberg Variations, when done right, can be truly transcendent. Perhaps the most groundbreaking example is the 1955 album recorded by Glenn Gould, who eschewed traditional tempi and skipped the repeats, distilling Bach’s work to its very essence. In doing so, the eccentric Canadian pianist, just 22 at the time, shot to fame overnight.

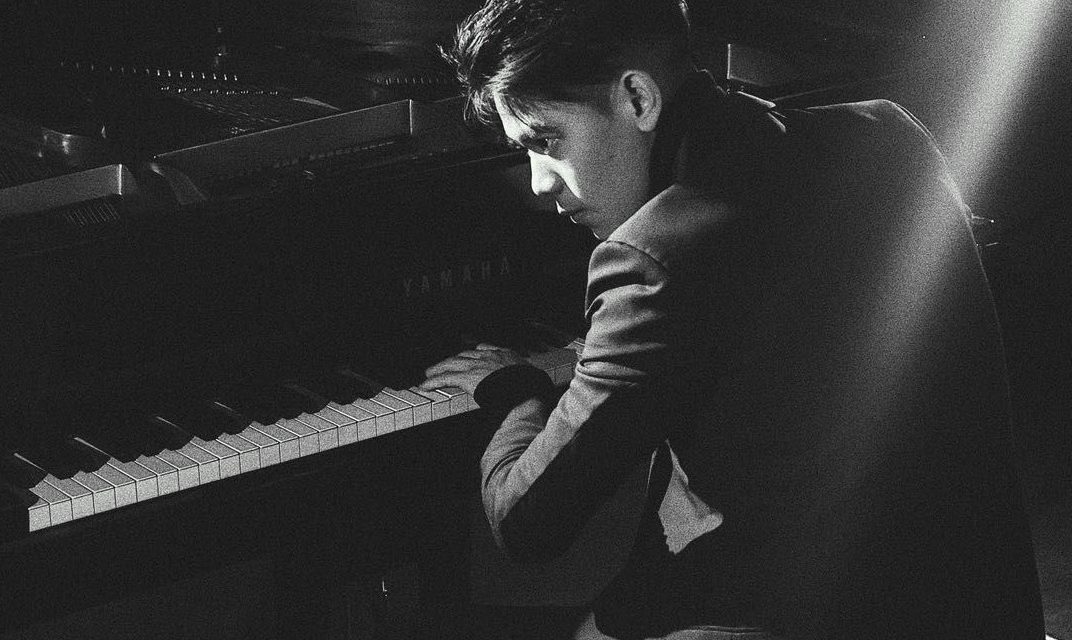

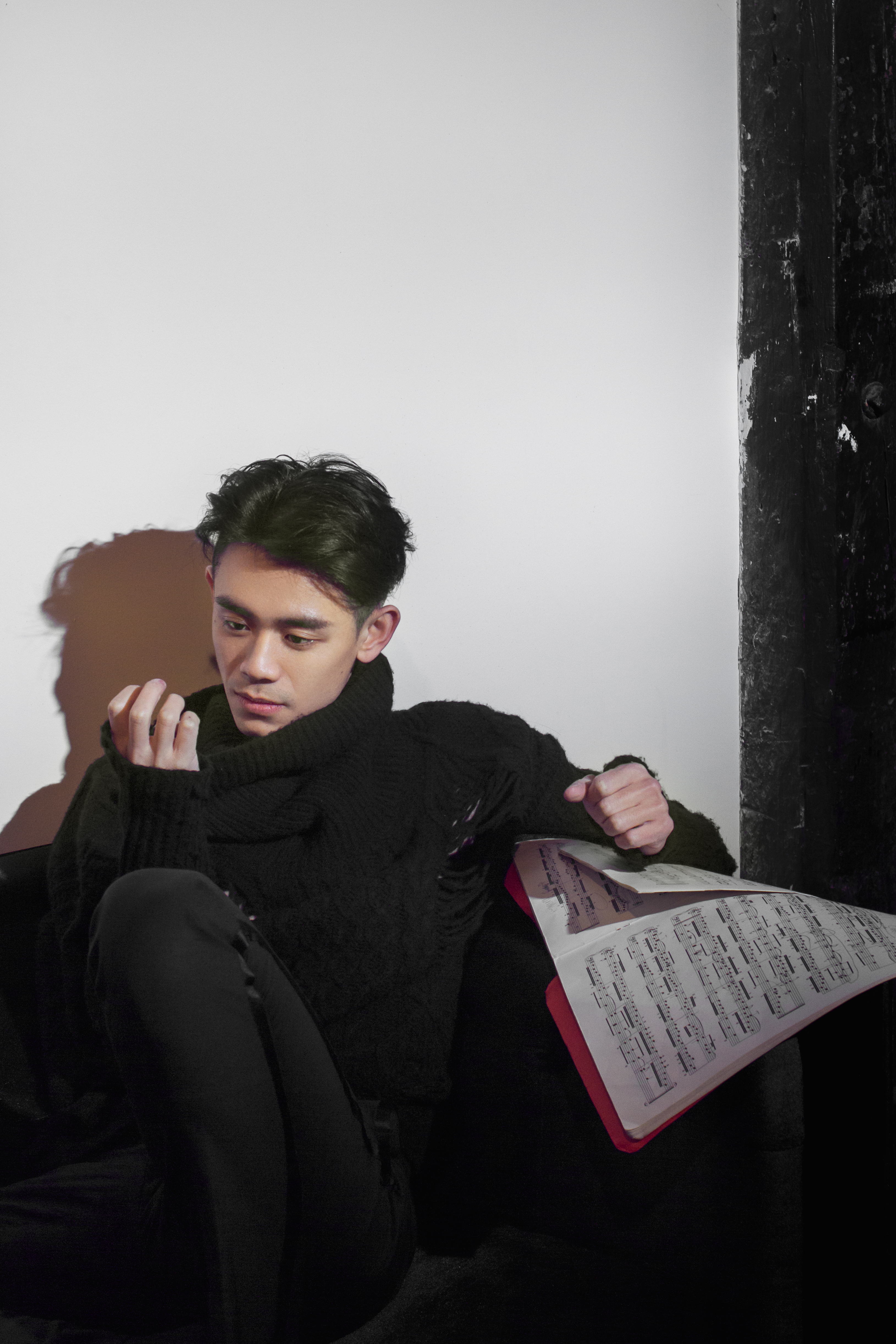

It’s impossible not to draw comparisons to Glenn Gould when considering Tianqi Du, age 25, a rising star in China’s classical music scene. In the sea of up-and-coming piano talent, Tianqi Du has forged his own identity. Embracing avant-garde experimentation and modern visual arts, Du pushes the envelope, extending himself far beyond the classical concert pianist route. His 2013 music video, Libido Fantasy, which Du himself directed and acted in, delivered the message loud and clear: Tianqi Du is a pioneer.

Naturally, I was eager to see how Du, a progressive, boundary-pushing artist, would interpret Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the epitome of Baroque purism. Inside Carnegie Hall, the evening began promisingly, with an elegantly shot video, reminding us again of Du’s multi-disciplinarian identity. For those in the audience unacquainted with the work, Du’s video passionately argues the significance of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, tying the threads both musically and mathematically. A voiceover narration by Du describes the two years he spent at Boston’s New England Conservatory, devoted to unlocking the secrets of Bach, and ends on the cryptic statement that the Goldberg Variations rescued him “from the edge of darkness.”

Context is everything. When Tianqi Du finally entered, there was, at first, a quiet hush, then tentative applause. Standing before us was clearly a young man who had fallen headfirst into the Goldberg pit of obsession.

The first Aria was close to perfection. There was a sense of giving in to the piece, as each note perfectly melded into the next. What was distracting, however, was the over-emoting. I tried to understand Du’s wide-eyed facial expressions, which felt jarring to the piece and seemed to appear out of nowhere. Were they supposed to express wonderment? Happiness? Reverie? Or were they just unselfconscious, reflexive tics? Unfortunately, as we moved on to the brighter, more spritely variations, the wide-eyed emoting became more frequent.

Tianqi Du began to mouth along to words only he seemed to know. Having seen Du’s other performances, this wasn’t the first time over-emoting has detracted from the actual playing. Whether a pianist realizes they’re doing it or not, excessive facial acting takes away from the real performance–the fingers seamlessly gliding over the keys, the careful articulation of the notes. More troubling is the striking similarity to Glenn Gould, famous for hunching over the piano and humming, singing, and muttering as he played. While Tianqi Du may have developed his style of emoting all on his own, it’s difficult not to label this behavior as imitation.

While it would be easy to dismiss the over-emoting and instead focus on a flawless performance, alas, the technical aspects weren’t all there. Tianqi Du valiantly goes for those dangerous hand-crossings (right hand over left, left hand over right) in progressions that are nearly impossible to make smooth. Some of the notes are lost, mumbled rather than clearly articulated, and occasionally, a wrong note is hit. With the deceptively simple-sounding Goldberg Variations, there’s no place for mistakes to hide–each misstep is made glaringly clear.

In the introduction video, Tianqi Du expressed his wish to convey the way Bach blends philosophy, mathematics, science, and art through his interpretation of the Goldberg Variations. There are moments during the performance that feel true to that spirit. The first aria and the repeated aria at the end, as well as Variation 25, have such a sense of wondrous harmony, of pure unity. In other areas, the performance feels studied and belabored. Unlike Glenn Gould’s legendary 1955 recording, which passes through the Goldberg Variations like an effortless breeze, with Du’s performance, you could certainly feel the effort.

French-Chinese pianist, Xiao Mei Zhu, describes the Goldberg Variations as a “Taoist blend of profundity and spontaneous silliness.” In Du’s Carnegie Hall performance, the profundity is there in spades, but the silliness is not. A combination of the over-emoting and Du’s trademark intensity, the joy felt forced, exaggerated event.

Undoubtedly, Tianqi Du has the potential to become an iconoclast, breaking the barriers of classical music and performance art. Here, though, his endeavors don’t quite pay off. Overall, Du’s interpretation of the Goldberg Variations was refreshing, but not revolutionary.

The performance by Tianqi Du was roughly 80 minutes long. There was no intermission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kathy Tao.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.