Brian Friel’s classic play about the blending of Paganism and Christianity in 1930s Ireland is more than 30 years old — and I remember seeing the original production from Dublin’s Abbey Theatre when it visited the National Theatre in 1990. That haunting production, directed by Patrick Mason, had a fine mixture of wistfulness and passion. Its atmosphere evoked an Ireland with direct links to JM Synge, John B Keane and Samuel Beckett. Since then, the winds of change — from the Celtic Tiger to Brexit — have blown away this world. And theatre has not been unscathed.

I also feel that productions of Irish plays are now divided into a before and after by the advent of playwright Martin McDonagh in the mid-1990s. His scabrous and ironic accounts of rural life are so powerful that other playwrights, from Yeats to Friel, now seem tame and outdated by comparison. So Josie Rourke’s new revival of Dancing at Lughnasa owes less to traditional interpretations of Irish classics, and more to a media world that sees Ireland through the lens of television programmes such as Derry Girls and Father Ted. Aptly, its cast includes Siobhán McSweeney (Derry Girls) and Ardal O’Hanlon (Father Ted).

At first, all is familiar: the giant Olivier stage at the National Theatre invites us to contemplate a lush and verdant Ballybeg, County Donegal, in August 1936. It’s a big theatre and the set is almost absurdly huge, suggesting the American Mid-West more than the smaller scale of provincial Ireland. But never mind, here comes Michael, the middle-aged narrator who looks back at his seven-year-old self, and the five Mundy sisters who brought him up: righteous school teacher Kate, sadly humorous Maggie (McSweeney), glove-knitting homebodies Agnes and Rose (who has learning difficulties), and his unwed mother Chrissie.

Poor and frustrated, the sisters — in what is surely a nod to Chekhov — endure and work hard, while also wishing for an escape from their crowded home. As the harvest festival of Lughnasa approaches, they have welcomed their brother Jack (O’Hanlon), a missionary priest who has returned in disgrace from working in Ugandan leper colony, and are visited by Gerry, Michael’s usually absent father, a chancer who at the moment is selling gramophones to villagers. Their melancholy existence is beautifully evoked by the older Michael’s monologues, which describe his memories and his nostalgia for the past.

In his account of how Roman Catholic faith rubs shoulders with old pagan feelings, Friel stresses the visceral power of music, played on the family’s wireless, and the need to dance, the physical expression of joy that bursts all the bounds of strict conformity. The play’s most famous scene, which is a wild stomping dance performed by all the sisters, is a great crowd-pleasing early highlight. As choreographed by Wayne McGregor, it rightly gets an ovation. But darker shades soon cloud the joy of the dance: industrial change threatens Agnes and Rosie’s cottage hand-knitting; Gerry volunteers to fight in the Spanish Civil War; and Jack is suffering from malaria.

Central to the play’s main theme is not only the contrast between a puritanical Catholicism and an older pagan belief holding on in the Irish countryside, but also the case of Jack’s experiences in Africa. Having lived with the Ryangan people, he enthusiastically advocates for their pagan practices, which include wild trance-like dancing and polygamy. Basically, he “went native” and, to the horror of the straight-laced Kate, he still proclaims his joy in this other world. At the same time, Friel shows how Gerry’s recruitment to the International Brigade is a comedy not so much of errors as of ignorance.

As can be expected in the post-COVID theatre world, this sell-out show is a populist feelgood evening, and Rourke’s production is brightly coloured rather than subtly shaded. Using the large resources of the National, Robert Jones’s set looks like something out of a 1930s Hollywood blockbuster, with its winding Yellow Brick Road and Oklahoma-style wheat fields in place of Irish paths and meadows. The trees are as huge as American redwoods. Likewise, the Mundy home is quaintly retro rather than impoverished. Among this richness, it’s hard to believe that the women are really struggling.

Rourke has also not made much sense of the domestic scene: the actors perform their household chores with a singular lack of conviction, and the existence of the deliberately invisible child Michael only fitfully crosses their minds. In a similar fashion, they seem to think that their cottage has flexible door spaces and panoramic windows. Although this is an ensemble piece, the cast are individually good, but have little mutual rapport. Newcomer Alison Oliver is both love-struck and despairing; Justine Mitchell’s Kate is both authoritarian and vulnerable; McSweeney’s Maggie is both wise-cracking and sad; Louisa Harland’s Agnes is both aching and lonesome; and Bláithín Mac Gabhann’s Rose is sweetly good-natured.

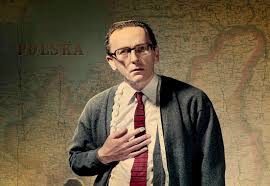

As for the men, O’Hanlon’s Father Jack mixes a suggestion of mental collapse with the sheer pleasure of religious heresy, Tom Riley’s Gerry is both charming and infuriating, while Tom Vaughan-Lawlor’s adult Michael is a narrator who gives some of Friel’s most rapturous and poetic lines a perfect articulation. Although there are some lovingly created moments — a head on a sister’s shoulder, or a quick glance across a crowded room — in general I felt that Rourke and her cast could have done much more to give emotional life to this classic play. As it is, this is a fun evening, with very few moments of darkness, and that underplays the story’s potential.

- Dancing at Lughnasa is at the National Theatre until 27 May.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.