Review: Bran Nue Dae, by Jimmy Chi and Kuckles and directed by Andrew Ross for Sydney Festival.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people.

It is exciting to see such a range of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander productions offered at this year’s Sydney Festival, including the first major revival of the 1990 award-winning musical Bran Nue Dae.

As my son and I arrived, we were greeted by a crowd of people dressed in their finest. There were many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander theatergoers who, like us, were excited to see a production written and performed by Aboriginal people. There was one particular young Aboriginal girl singing “nothing I’d rather be, than be an Aborigine!”

Despite her mother’s attempts to silence her, she was clearly happy to be at the event.

In Bran Nue Dae, Willie (Marcus Corowa) is expelled from the boarding school he is attending in Perth for “stealing” chocolates.

On the streets of Perth with no way to get home to Broome, he meets up with his Uncle Tadpole (veteran actor Ernie Dingo, in the role he played in both the original production and the 2009 film adaptation). Together they begin their journey to their homelands.

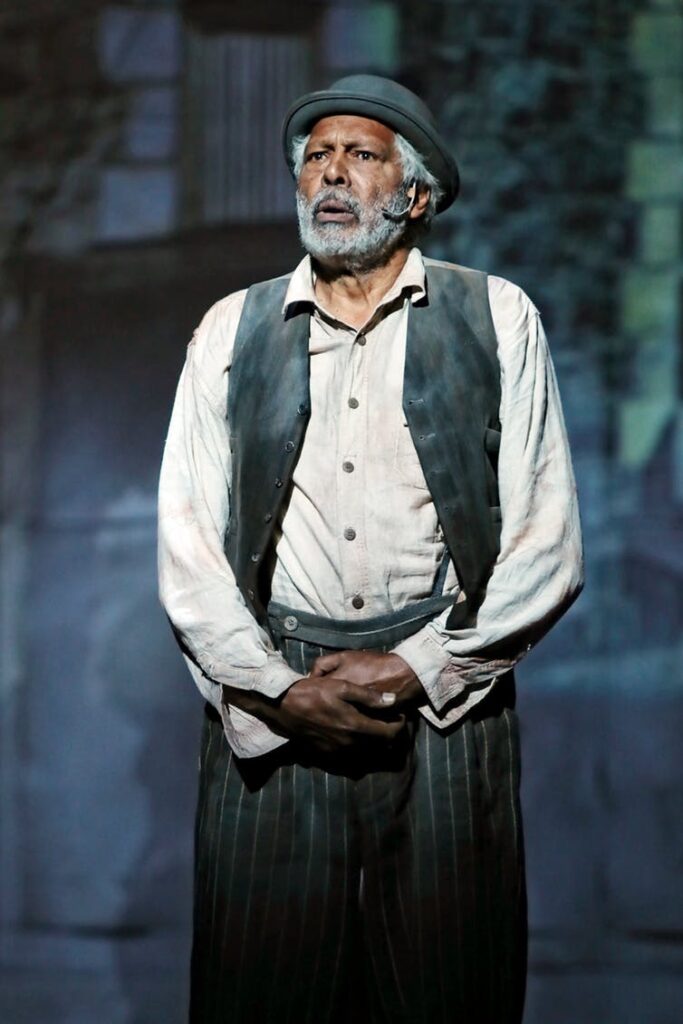

Bran Nue Dae by Jimmy Chi and Kuckles and directed by Andrew Ross for Sydney Festival. Photo Credit: Prudence Upton.

Uncle Tadpole throws himself in front of a combi van driven by German tourist Slippery (Callan Purcell) and free-loving hippie Marijuana Annie (Danielle Sibosado), and the travelers feel obliged to give the pair a lift.

Together, they take a road trip 2,200km north, encountering Willie’s love interest Rosie (Teresa Moore); finding themselves in the Roebourne Lockup; swimming in a watering hole on the Roebuck Plains; before making it home to Broome and the mangroves.

A semi-autobiographical play by the late Jimmy Chi and his band, Kuckles, Bran Nue Dae is set in Western Australia in the 1960s: oppressive times for Aboriginal people.

Opening with a song set in the future by an elderly Willie, “Acceptable Coon” is a powerful introduction to the political messages of the work:

“They taught me the white ways, and bugger the rest,

Cause everything white is right and the best.

So learn all the white things they teach you in school,

And you’ll all become acceptable coons.”

Chi’s lyrics draw attention to Aboriginal deaths in custody, dispossession and assimilation, and the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

One of the more somber songs, “Listen to the News”, asks: “Is this the end of our people?”

Thirty years on, their content is still relevant.

Aboriginal resilience

My son had not seen the 2009 film, and I was keen to see what he thought of the performance. Like me, he very much enjoyed the music. The singing is exceptional, highlighting the immense talent of the cast.

But there was a sense for both of us that the music itself was the highlight and the storyline was somehow obscured.

For my son, this was particularly notable: he came to the event fresh and expressed his difficulty in being able to follow the plot, despite being an avid theatergoer.

The original stage show had much more dialogue and the film with screen director Rachel Perkins was able to expand the narrative and provide far more context. This production cuts out a lot of the dialogue from the original script.

We both came away feeling that more dialogue would have ensured the audience understood the politics of this wonderful play which, for me, in its original form brilliantly documents many aspects of Aboriginal history in this country.

Both my son and I enjoyed the play immensely, although as a scholar who has a great deal of interest in the politics of identity I was left with a few questions.

I understand the reconciliatory theme of the show and the message that we are all “one race.” However, given the focus on identity, we see regularly in the media, some of the “discoveries” of Aboriginal identity hung in the air uncomfortably.

In one scene, Marijuana Annie has an epiphany and announces “I too am an Aborigine!”, remembering Black faces around her as she was removed as a child.

Here, Marijuana Annie is played by an Indigenous actor, unlike previous renditions (Missy Higgins played the role in the screen version), and so her revelations are not as problematic as it has been. But still, the cast breaks into song, making light of the situation and offering a more palatable version of such histories.

There is more room for the production to explore the violence of colonialism while retaining Chi’s lightness and humor.

Bran Nue Dae by Jimmy Chi and Kuckles and directed by Andrew Ross for Sydney Festival. Photo Credit: Prudence Upton.

Bran Nue Dae is an Australian classic. It tells of the enduringness of colonialism and does so in a way that invites audiences into the humor of tragedy and the ways in which Aboriginal people express resilience to colonial rule.

And, like the young girl outside the theatre, by the end of the play the audience – including my son and I – were singing along.

This article appeared in TheConversation.com on January 19, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

By Bronwyn Carlson

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Bronwyn Carlson.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.