Mika Johnson is an artist with a background in theatre, but also a film director. Besides this, he makes music and works as a photographer. He is the director of VRwandlung, a production that is based on Kafka’s Metamorphosis. The production toured around the world, but recently it was presented also at Hungary’s first VR-focused event, Vektor VR section in the frame of 16th Verzió Human Rights Documentary Film Festival in Budapest. On this occasion, we asked him about how he became a VR creator, about the challenges of adaptations, and the special mindset that VR might require.

Ágnes Karolina Bakk: You have a very colorful professional experience, is there any moment from it that you would highlight?

Mika Johnson: I’m interested in many things but never one thing in particular for an extended period of time, which is both a blessing and a curse. This means I can never devote myself entirely to one medium or subject. For example, during various periods I made music, took photographs, and made films, all with equal energy. This is also true for the subjects that inspire me. At the moment I’m studying mushrooms, mycelium, anthropology, miniatures, and history. And XR has only just begun for me. In the past, this made finding funding very difficult, as funders want you to do one thing, but I’m finally getting lucky and can continue with my various interests in multiple media.

A.B: You were at Oberlin College. What was your path from there to VR/XR?

M.J: I studied theatre and religious studies at Oberlin College, with a focus on ritual, which is where theatre as an art form finds its roots. These studies later helped me as a filmmaker, in the sense that I’ve remained committed to experimenting with acting, ritual, mythology, and space, all of which have important overlap.

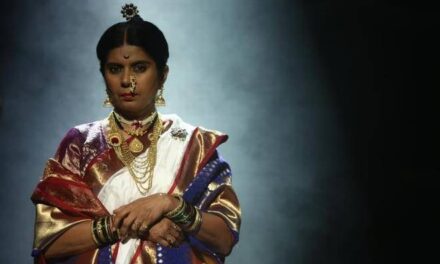

Mika Johnson (by Jussi Manni)

For example, my first two films, The Mountain of Signs (2003) and Yonder (2007), doubled as rituals that were co-authored by the participants, who were also the actors and writers. I later directed a web series, The Amerikans, which included 15 episodes, where I invited 15 subjects to perform their memories and dreams, but this time for short, 3 – 5-minute documentaries. These practices didn’t lead naturally to working with virtual reality, but my interests with performance and co-authorship were embedded in my original reaction to VR when I first got to experience it.

My introduction to VR was thanks to Shahid Gulamali, VRwandlung’s producer, who asked me to conceive and direct a project for the HTC Vive. While researching Kafka and his work for a project that I was working on, I realized that the Vive’s room limit, which was 4×4 meters at that time, could double as Gregor Samsa’s bedroom as it was described in the story. This is where my original inspiration for VRwandlung began.

A.B: What do you see as challenges in adapting stories for VR?

M.J: The biggest challenge for me was adapting Kafka’s story in a new and unique way, using space as the main narrative device. To do this I studied Kafka’s bedroom, which during the time he wrote The Metamorphosis was identical to Gregor Samsa’s room (Hartmut Binder published a blueprint), including having three doors, a desk, one window, etc. This inspired me to create an experience where participants could move around a simulated version of Samsa’s room, as a giant insect, while simultaneously discovering a world of hidden details related to Kafka’s own biography (his books, photographs, postcards, notes, etc.). This two-tiered level of interaction, the second being an embedded narrative that comments on the author himself, gave me a completely new way of exploring how to tell a story.

Photo courtesy of zip-scene.com

A.B: How did you start the adaptation process of Kafka’s Metamorphosis? What were your “learnings” in the adaptation process?

M.J: Everything for me began with the text, specifically Act I of the novella. After reading and rereading the story half a dozen times, I began to come up with a four-minute script, which I acted out with an assistant. We would record the dialogues, make cuts, and record again, for several weeks. Simultaneous to this, I met with the animators Ondrej Slavik and Vojtech Kiss to list all the things that Samsa should have in his room – items that they would later craft by hand. Most of the time we stayed faithful to the story but in some cases, we altered specific details to fit the mise-en-scène that was intended to lead participants around the space. This included swapping out a door for a mirror, which wasn’t in the original.

What I learned is that sound, at least in VRwandlung, is over 50 percent of the VR experience. Our sound designer Eli Stine did an amazing job to the degree that by the time we incorporated his sounds with Joseph Minadeo’s score, we were able to remove a lot of the dialogue as it was no longer necessary. The sounds of becoming an insect, which included the movement of the antennae, mandibles, body, etc. along with the music, which slowly climaxes, was in the end far more alienating than the voices yelling from behind closed doors. We decided to emphasize those sounds and it worked! This was such a learning curve for me that for my next VR project, I will likely begin work first on the sound design prior to creating any visuals.

A.B: What did you find as the most intriguing technical problem in developing the project?

M.J: For me, a fascinating technical challenge was creating something interactive, as I’ve mainly worked with linear mediums. I also don’t play computer games and I tend not to like to have a goal or objective when I confront a piece of art. My preference is to daydream and get lost in a world, whether that’s a painting, film, or piece of music. I wanted VRwandlung to have that same effect. So what to do with interactivity? We resolved this by removing the participant’s options, which had an uncanny effect. For example, you wear gloves and slippers with trackers that double as insect arms and legs in the VR space. But you can’t really do anything with them, per se. Your hands can’t pick up objects or open doors, so you soon realize there is no goal in the space. This then focuses the interactivity on one thing: becoming Gregor Samsa, which you immediately realize the moment you see yourself in a mirror. This disappoints the gamers but theatre and performance art fans tend to really like it.

A.B: How do you see the near future of VR/XR productions?

M.J: I just got an Oculus Quest and was disappointed. Not by the technology, which is impressive, but by what’s currently available in VR, which are mainly traditional video games. To expand the appeal of the medium, I think producers will have to fund more culturally interesting VR projects that also are available to home consumers. I say ‘home consumer’ because there are already many fascinating experiences out there but most of these are only available at exhibitions, museums, or festivals. But because companies like National Geographic and NASA are creating experiences for the home consumer, I hope we will start to see a whole range of new experiences, including educational pieces – say to adapt literature or history, etc. I can imagine learning mathematics, languages, or philosophy in VR as well. The virtual reality tour of Anne Frank’s hiding place, titled The Anne Frank House VR, where she and her family lived with four other people for more than two years during WWII, is an exceptional example of this. The piece is available for free for Oculus and really showcases what’s possible related to incorporating a diary, biography, history, an architectural tour, etc. This is a new form of storytelling and, hopefully, a direction the medium can continue in. At the same time, this split between the home consumer and exclusive experiences will likely deepen, as the setting, or staging, for VR pieces are also a great way for artists to expand on their works in ways that have a far greater impact, as the experience themselves become one subset of a larger narrative.

A.B: You are also teaching and giving workshops about the creation process in XR. How do you start these or what are you emphasizing more for your student? How can they change their mindset to think in VR worlds or How do you help the participants to understand the thinking in 3D?

M.J: I begin my workshops with discussions about what a medium is. I quote Marshall McLuhan – “The medium is the message” – and we look at how mediums change the way we interact with and experience information. This is also true for distribution platforms as well. Watching a film at a theatre, on a laptop, or on a smartphone are three different experiences. The same is true for VR. So we begin by discussing how setting changes our experience of all forms of information.

My workshop’s emphasis, however, is on interaction and roomspace, as those two features are what make VR a new medium. The roomspace is what allows artists (by which I mean programmers, directors, producers, and creators from a variety of fields) the possibility of immersing users into the space of a protagonist; whereas the interaction aspect becomes the primary mode of narration. So creators should think in terms of emergent, non-linear narratives, which really just means story structures that manifest as users make choices. This is why it’s helpful to study game design, as they’re at the forefront of these narratives, which began in literature in 1976 with a series of choose-your-own-adventure children’s books by Edward Packard. But studying other mediums is also helpful, for example, forms like cinema, or moving images (VR is 90 frames per second or more), play a major role in VR, which is really a mixed medium. For example, as I mentioned earlier, sound is at least 50% of a VR experience. This depends on the piece of course but understanding all these elements can only be helpful.

A.B: What is your next project or what is your long term endeavor regarding creating in VR?

M.J: I am currently working on four pieces at the moment. One is an adaptation of the work of Bruno Schulz, a piece titled The Republic of Dreams. Another project, titled Mycorrhiza, will allow users to interact with a forest above and mycelium below in a space that mimics the wood wide web. Virtual mushrooms will play an important role. The other two projects are still in the development phase, however, I have also been working as a consultant, which is exciting because I get to know how others are pushing the boundaries of this medium, as VR remains a field for pioneers. Long term, I have no idea how where I’ll be with virtual reality. I am still very much a filmmaker, with two features that I am presently working on, but as long as I feel challenged and inspired, I imagine VR will play a big role in my work as an artist, as I’ve only just begun.

Guest editor: Ján Tompkins

This article was originally posted at zip-scene.com on December 22nd, 2019, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ágnes Bakk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.