The Russian winter sprinkled with the aristocratic splendor of Imperial Moscow and Petersburg in Leo Tolstoy’s all-time classic novel tells its extraordinary, never finished and always challenging story. On the stage of the Novi Sad Theater/Újvidéki Színház, the play Anna Karenina, directed by Macedonian director Dejan Projkovski, presents a painful drama, tension and conflict between the characters and within them. The elegance of the 70s of the 19th century and aristocratic opulence mask the great suffering and reveal the dark charms of the capital’s literary template. The stage presentation of the novelistic drama of dramas begins, and the book of unfulfilled and unhappy people, love, and families opens.

Time stands still on a giant round station clock that slowly rolls from one end of the stage to the other side – showing a Moscow railway station. This place, the railway station, is where the fatal lovers will meet for the first time. In front of the audience are scenic images of gentle whiteness and the darkest blackness of girls’ dresses, winter suits, fur coats and scarves, snow and ice, pearls of debauchery and silk shirts of immorality. Promiscuous licentiousness and marital infidelity alternate where the souls lay – on the train, railway station, ice rink, ballroom, and endless rows of red plush seats, which only can be seen in compartment coaches and theatres or cinema halls. All of that is scenographically colored to give several levels of the situation with rows of lacquered black doors through which a strong draft pulls, unfolds, and opens the most hidden spaces of the human heart and soul. The Russian spirit inflames souls stunned by vodka in the time of tropak and barynya sounds and dances, in scenes of brotherly and friendly love and loyalty, which are characterized by the talented acting collective playfulness of this famous theatre ensemble, skill and beauty, technique and aesthetics of the game in the pursuit of winning freedom (collective and individual ), to fulfil the order of his soul. Mass scenes of balls, opera performances, horse races, reading from coffee cups as expressions of public events, presentations and commentaries, contrasting scenes of brothel debauchery and village idylls flood the play with enormous bursts of energy. The fiercely staged, deeply thought-out and aesthetically beautiful direction of Dejan Projskovski incorporates, into the theatrical game, ingenious author’s music, ballet, opera and film productions, leading the audience through a harsh love fairy tale.

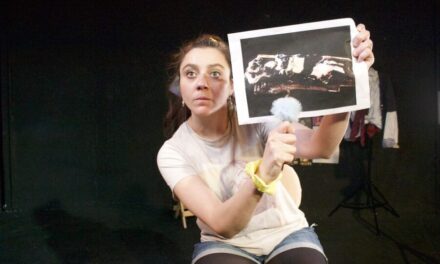

The main character of the heroine in the story is a hero and victim of her personal choices buried in the society of the unfree and hypocrites. Two actresses, Béres Márta and Fülöp Tímea alternately play the role of Anna Karenina and create performances quite different from each other. The division presents its character duality because each actress plays for herself and colors the play with unique tones – setting a special feeling to the artistic atmosphere. Quite simply, both in Tolstoy’s novel and in the visions of this work, as well as in Projkovsky’s play, the character of Anna dominates and culminates in the role of a woman, mother, lover, sister, and human being torn under the burden. She stands crucified on her own cross because by choosing one, she loses the other inevitably. The impressive and powerful actor’s external and internal emotional struggle, accompanied by social chaos, a multitude of intrigues and sad life stories, expresses even more miserable and more desolate lives, haunts the protagonist in her immense suffering on the way to achieving such and such an amount of happiness that corresponds to her ravishingly passionate character. Her socially acceptable temperament, who held back, hesitated and presented the image of a moral and decent woman due to not agreeing to lies and hypocrisy, suddenly is rejected. She gets a label and encounters social condemnation at every step. In a world that makes life a dungeon, Anna’s free spirit is waging a ruthless fight, which she knows she will eventually lose. She will end up broken and run over, not by anyone from outside but by the other Anna hiding inside her, Karenina’s alter ego.

Mészáros Árpád plays the character of Vronsky with precision and strong feeling – the best example of a Petrograd youth who himself, without calculations, dared to follow his heart. The theatrical audience sees Vronsky as a count at the highest level of social status, a charmer of big reputation who, surrounded by a cloud of mysticism, alternately captivates and conquers a woman’s spirit until his gaze meets the eyes of Alexei Karenin’s wife (Német Attila). The magnetism of Anna overcomes his macker manner, and he is immediately captured and conquered. Vronsky truly loves Anna, and His love will lead him to meet and understand the deepest and most devoted side of his being while defending the woman he loves. But on the other hand, he will not be exposed to ostracism from society, as a man of his time and rank gains more (rather than loses) on authenticity. Ana will become possessive, full of anger, jealous, wildly irritable, and in bouts of mental crises due to her imprisonment, and Aleksey will try to find a way out. The loss of Anna is the loss of his soul. His free movement will turn out to be a trap, he will face the fact that he failed to make her happy, preserve, and save her, and it will take away the meaning of his existence, the purpose of his living.

The theatrical performance is full of passion, intrigue, mystery and tragedy. The director uses very effective symbolism, which he explains thoroughly and presents on stage forbiddenly unspoken words or the end of which is not yet known, just like a hinted symbol of small children’s toy of a moving train that Seryozha always carries with him and which silently moves around the stage by itself. The game with the words written on the monumental door between Kostya (Pongó Gábor) and Kitty (Dienes Blanka / Dedovity Tomity Dina) serves them as a perfect manner of shy recognition of mutual love. Rapture and passion show and express the bites of an apple which indicates the original sin and all the future sins that the human race will never resist. Pearls – a status symbol that will break and scatter at some point, talk about the future.

In the form of closed black aristocratic doors and darkened in the shadow of imaginative windows, the flexible scenography is the work of Valentin Svetozarev, which creates the illusion of large ballrooms and intimate and elegant rooms of a family home of that century. But when all the hugely monumental doors and great glass windows open, the view reaches into the depth of the scene, and all the intimacy is lost. Everything becomes exhibited, reviled, exposed, and accessible to the big city – the aristocratic society looks and listens with its wide open eyes and carefully positioned ears and entirely gets involved in human happiness and shame. All secrets become public, and the audience witnesses it (does it, and on whose side is it complicit?). Also, against these and similar metropolitan scenes and alternately with them, the gates swing open to show, as if from the other side of a broken mirror, the contrast, the idyllic life in the countryside, the marriage and happiness of Kitty and Levin. The depiction of mowing described in the novel as a closeness and understanding between the classes, as an expression of the spirit of the people, an image of immediate action that is played out magically on stage, stands out. In the character of Levin, the elemental and planetary simultaneously, the simplest and the most complex understanding for every human being is given (for Anna Karenina in particular, for whom Levin instinctively feels that she is the most vulnerable and the most unhappy and that she needs human compassion the most).

White silk and fur, red velvet and purple plush, black lace and theatre curtain are the colours that dominate the scene. Luxurious costumes, capes and coats, formal suits and rich jewellery were put together and presented by costume designer Marija Pupučevska. The infamous ball where the two lovers met, accompanied by exciting rhythmic choreography with “techno” music, as well as the horse racing scene, which was vividly designed as a pommel horse jumping competition, are just some of the innovative images and incredible artistic impressions that remain etched in the minds of the audience. Olga Panga’s stage movement leaves a great impression in stylized scenes, giving them soul with her powerful rhythmic impulses. In the background, the old Russian song “Shine, Shine, my star” is melancholically heard and listened to in moments of mental breakdown on the ground perspective. Goran Trajkoski arranged the music for the play.

This play teaches us that the driving force is love behind everything – happiness and misery, life itself. The novel Anna Karenina by Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, if approached from the point of view of the continuation of the novel in verse, “Eugene Onegin”, by Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, develops the story of a married woman whose love she questions. It follows the theme of a little man and great sadness in the world of people. Mystical cigarette smoke, cold ice falling on the theatre stage’s floor, drops of alcohol pouring down the tables, and scattered pearls remain on the smoky place of act as proof of what was happening and had happened. The clock crossed the stage for the last time, and the train sound was heard in the distance by silent scenery. It was dark. The sad story stops here even though its continuation is predictable to become another tragedy – the feeling of the beginning of a new misfortune is present. The audience does not move or breathe for a long time in that darkness, deeply shaken by the performance. The endless sadness of the story is differently told by the interpreter each time like a human curse dies out cyclically to be reborn again. Literature with God himself becomes a witness of human destiny. The theatre represents everything that life has not said. Pearson takes battles with its own being. A theatre that interprets the classics puts on the stage works that are bigger than anything human, reminding us of the past and encouraging us to choose to influence our lives and confront the (already determined) future. Or it warns us (the audience placed on the other side of the mirror/stage) to follow the fateful course of history. Its immutability.

As Anna’s thoughts drift with the last words: “God, please forgive me”, arises a new voice against that every hope ends in despair, that every laugh ends in great pain.

Anna Karenina, directed by Dejan Projkovski, will remain in the story of the Novi Sad Theatre/Újvidéki Színház as one of the most performed and awarded plays of this theatre.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emilija Kvočka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.