I highly respect and admire Schaeffer’s escalation of innovations but it creates the effect of “always something different, and thus always the same.”

Word has just got out that Bogusław Schaeffer, almost exactly on his eightieth birthday, received an annual scholarship from the Ministry of Culture. Not a State Award of some kind, not even the Opus award, but that paltry scholarship intended for talented youth and inept artists unable to live off their artistic work. It came as a shock to me that someone of such merit and such (musical and literary) achievements had to write an application, attach examples of completed and drafts of planned works, then put it all in an envelope, send out, and slip into anticipation. Of course, he must have had his reasons. Of course, there may also be some so-called objective reasons.

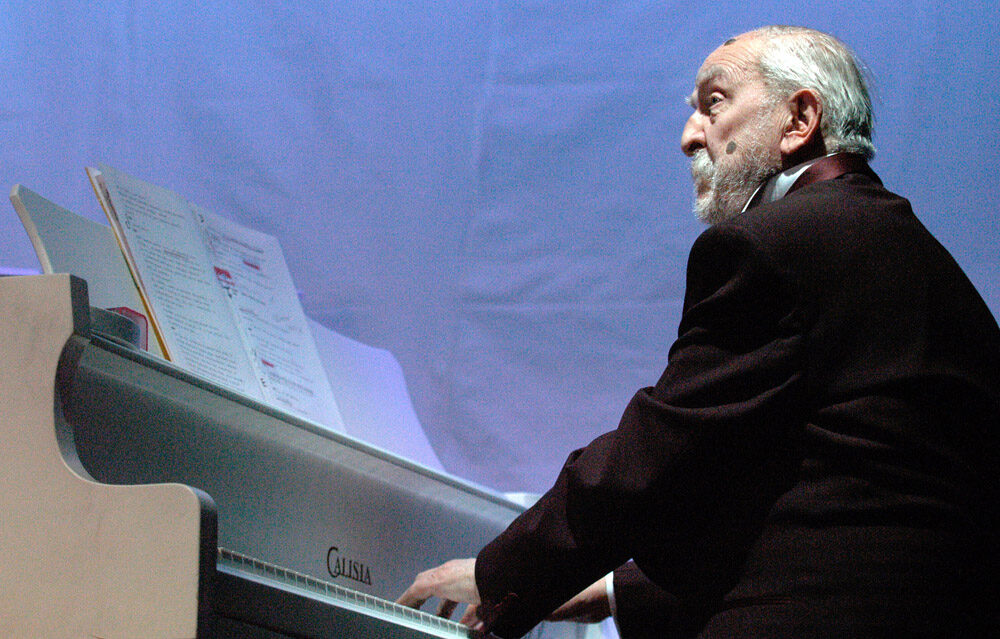

Bogusław Schaeffer, photo: PAP

I am writing about “such merit” and “such achievements,” but what are they actually? Is anyone familiar with them at all? Does anyone remember? The problem with Schaeffer’s musical oeuvre is its excess, in two respects. First, it is an excess of quantity: over the last decade alone, Schaeffer wrote twice as many works as, for example, Schönberg throughout his entire life. What is more, all that (with few exceptions) is still in manuscript–no one will perform it over the next 200 years, much less publish it.

I once visited the Schaeffer family flat, at the Kolorowe housing estate in Nowa Huta, and I saw piles and mountains of folders full of music paper covered with calligraphic handwriting (Schaeffer is a calligrapher, even if he won’t admit it); in that respect their home may only be compared with the apartment of Maria Janion and the archives of the Institute for National Remembrance. There are extremely interesting things there, concerts for all possible instruments and their sets, including even a concert for the violin and a female choir. But the way it is there is such that it is not there, while myself, for example, I would be happy to actually listen to all of that. But who is going play it for me?

Boguslaw Schaeffer’s 81st birthday

Composer, musicologist, playwright, graphic artist and educator, born June 6, 1929, in Lviv. One of the most colorful and prolific Polish composers, the author of more than 440 compositions of various kinds from solo pieces up to mega-symphonies, operas and dramas (translated into more than a dozen languages including Estonian, Hungarian and Hebrew), a music writer (books such as Klasycy Dodekafonii [Classics Of Dodecaphony] and Leksykon Kompozytorów XX Wieku [Lexicon Of Twentieth-Century Composers]). Stefan Kisielewski called him the “father of new music in Poland.” In a few days, Dwutygodnik will feature another view on Bogusław Schaeffer from Ewa Szczecińska.

Actually: why not play it, if it is all original, innovative and wonderful? Why not, if it is with an utmost thrill that I recall the few presentations of Schaeffer’s works at the Philharmonic? As opposed to, for example, Penderecki or Kilar’s, who no longer need to apply for a scholarship from the Ministry of Culture because they are always on the repertoire.

This is where the problem of the second kind of excess comes in: the excess of quality. Each of the well-known composers of the twentieth century can be assigned a creative method by which we listen to their music. Schaeffer’s method is a hybrid: it is based on creativity rather than consistency. His works lack repetitions and formal framework to help the audience figure them out somehow, they keep moving forward and in multiple accumulated layers.

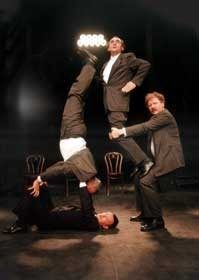

Kwartet, STU Stage Theatre in Cracow, photo: Ryszard Kornecki

The same is true of his theater, once extremely popular, now somewhat despised. But once we really used to like works such as Audience, Scenarios, and other plays, and today they are still witty, intelligent, ironic and critical. So why are they played so seldom? First, I think: probably because they are comedies and comedies become hackneyed the fastest. But after all, Gombrowicz wrote comedies, Mrożek has, and Głowacki is writing them; in the twentieth-century writing comedies generally did not stand in the way of greatness–on the contrary, take for example Beckett and Buñuel, not to mention Fellini. Or Allen.

And it suddenly occurs to me that Schaeffer’s greatest career as playwright coincided with the success of Laskowik and Smoleń. Those were the golden times of Polish cabaret, after all. This is where the rub is. Schaeffer’s plays have the structure of sketches–they are not dramas, just like his sonatas are not sonatas, while even the sonatas of Sciarrino and Ustvolskaya are.

Schaeffer’s artistic work does not oppose (as it is apparently believed) the various specific phenomena which came to an “end” at the end of the nineteenth century (such as tonality or coherence of the narrative), but rather certain staples of highbrow culture: depth, tragedy, and sublimity. Schaeffer keeps providing the audience with endless attractions, and in this respect, this is essentially lowbrow art, though it is difficult too. By the way, I do not think it means he is in any way inferior to someone like Górecki who applies just the rudiments, and no attractions. But at the same time I feel that while focusing on the outcome, Schaeffer does not know exactly what he is doing in the general sense, for all his intelligence. Or perhaps, it may be caused by his formal over-sensitivity, the specific assumptions of which have not yet been discovered.

Let me round off with merits. As he says himself, Schaeffer is the author of the first piece of music written on a typewriter. I saw that work in an exhibition of his graphic scores once and it is hard for me to imagine how it might sound (though it probably sounds like every other typical work of Schaeffer).

However, I think he has created a lot more music on that typewriter of his, and strictly speaking: he rewrote it. Were it not for his efforts to popularize new music we would have no idea what it is about at all. I first became familiar with most contemporary works, including The Rite Of Spring, via Schaeffer’s descriptions; many of them I can still only imagine based on his Przewodnik Koncertowy (Concert Guide) or Kompozytorzy XX Wieku (Twentieth-Century Composers) and some of them I will probably never hear.

Schaeffer is a strict, demanding yet expressive popularize. Let me give an example: I assimilated the music of Busotti in one go, though supposedly it is not “easy to digest.” It is thanks to Schaeffer that the whole spectrum of works that even he probably knew mainly from the scores is there my head, imagined and confirmed, and sometimes quite the opposite–dreamed, but understood better than I could ever figure out myself.

I, therefore, appreciate Schaeffer the enthusiast most, but thanks to him I can also live up to the demands of Schaeffer the composer and avoid being too much at loggerheads with Schaeffer the playwright.

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in May 2010 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Adam Wiedemann.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.