Tectonic Theater Company’s latest production at the Sheen Center in New York, Uncommon Sense, follows Moose, Dan, Jess, and Lali–four individuals living on the autism spectrum. Moose’s parents struggle to keep him safe. Jess must navigate through college, while Dan begins a new relationship. Lali’s mother takes her to yet another speech therapist, always hopeful that someday, she will be able to communicate with her daughter. As we watch the character’s face day to day challenges, the set itself seems to come to life with mesmerizing movements and projections, often revealing the characters’ points of view.

Uncommon Sense had its off-Broadway premiere at the Sheen Center in New York and ran for 5 weeks at the end of 2017. It was a moving play that got to shine a light on the realities of being a non-neuro-typical (a person living with autism spectrum disorder or other neurologically atypical patterns of thought or behavior) coping with finding love, interacting with new people and everyday struggles in communication. The play was by Anushka Paris-Carter and Andy Paris and was directed by Andy Paris. Set Designer John Coyne shares the thought processes that went into designing the show.

Unsworth: What sort of research did you develop for approaching this design?

Coyne: I think for us it was mainly about trying to capture the emotional side of things versus a realistic storytelling. It’s very hard to get into the head of someone who’s autistic, which is essentially what the play is attempting to do. I have a son who’s on the autism spectrum, so I had a little bit of insight through him, just what kind of things bothered him or a little bit of how he saw the world. Of course, that’s just him, not every autistic person. What we wanted to go about doing was to try and capture what the world maybe felt like versus what it looked like, how an autistic person might feel about how the world is around them. A lot of the research that we looked at had a lot more to do with the psychological journey, I think, than actual places. Certain themes emerged as we were researching and developing, things that wouldn’t make sense in a real space, things like staircases, pathways, that aren’t really clear where they go, where they come from, doorways that aren’t necessarily logical. Even things like transparent walls or structures that aren’t completely solid, and again, that don’t really represent what the real world is. Those are some of the things that we were working with.

Unsworth: The play is about four different characters who are living on the spectrum. Was there anything particular about a certain character or a moment in the script that really inspired you to create certain structures?

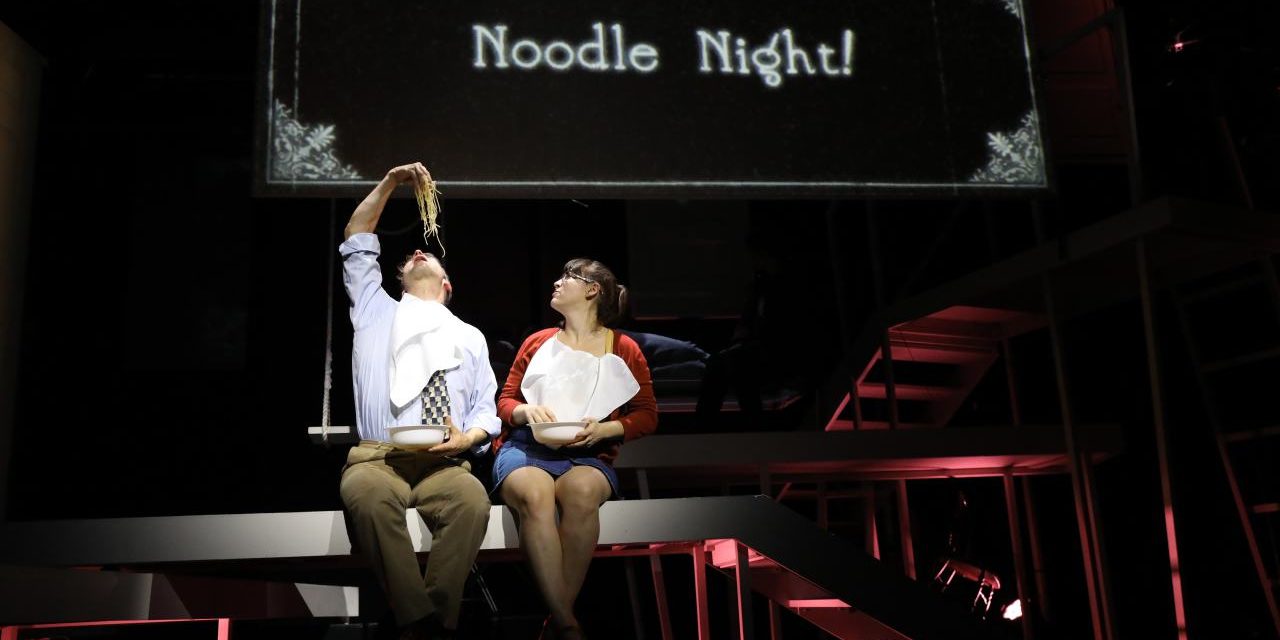

Coyne: Not particularly. Part of what we wanted to accomplish was orientation, that you really weren’t sure where you were or where you were going and that was a theme that I think worked for all of the characters. There are some things that deal with very specific characters. One of them is a huge projected anime character… there are certain elements of water that come into it that is related to the characters, there’s a swing… The overall design, though is trying to get at the sense of disorientation for all of them.

Unsworth: Did you have a certain goal in mind, like what would you like for an audience member to take away after seeing your set?

Coyne: The goal is pretty much to better understand the mind of somebody who has autism. Again, as we know, autism represents a wide, wide group of people. There’s a line in the play, “When you’ve met somebody with autism, you’ve met just one person with autism.” They’re all very different. I think I wanted it to be a structure or a framework in which their stories can be told. One of the theatrical devices was a lot of overlapping, so we wanted to use that as well. We overlapped visuals so the audience could draw parallels to what was similar, but to what was different as well. I wanted it to be about looking at the world in a different way, not in the way we see it every day, but about seeing it through their eyes, people on the spectrum’s eyes. There are moments of real beauty, but also frightening moments of terror that are overwhelming that can happen quite a bit for people on the spectrum. I think I was trying to create a visual wrap up of those different emotions.

Unsworth: How about you and your journey? You mentioned that your son was diagnosed with autism, do you think designing the set affected you in any way?

Coyne: We’ve had our triumphs and our struggles, you know, I see little bits of him in this play. I see bits of our struggle and our journey in this play, you know, not from any one character, but little bits throughout. Working on it has been cathartic. It hasn’t changed how I feel about my son, but it helps me find ways to share the joy of my son and my family with other people. Every set that I do, every production I work on, it affects you in some way, but this one was very rewarding, personally.

Anime Girl in the play Uncommon Sense, at the Sheen Center in New York, 2017. Photo Credit Joan Marcus. Written by Anushka Paris-Carter and Andy Paris and directed by Andy Paris under the artistic direction of Tectonic Theatre Project’s founder, Moisés Kaufman.

Unsworth: Why is the production Uncommon Sense important today? Why now and in today’s society?

Coyne: One of the most important things that our (American) society needs to address and have a dialogue about is diversity and inclusion and acceptance. I think there are many issues right now that are really challenging the issue of diversity and acceptance. It’s not just tolerance, but being willing to bring people into your world that are very different from you and to find the beauty in them, to learn the challenges that they might face and to really accept them as a part of your community. I don’t think that this is just about autism; this is a big issue that we face in America at this moment. The autistic community is growing. Statistically, more people are being diagnosed; I don’t know the reasons for that. But it is something that every school and community and family, in one way or another, is being touched by. It has no bounds as far as wealth or race or class or location. It is occurring in every single community and a lot of people don’t know how to deal with it or how to recognize it or how to be open to it, to appreciate people for just being people. It’s a really important conversation to have. It’s not just about autism, but autism is one of those issues that many people have to start addressing and understanding and embracing because it’s a part of our world.

Unsworth: How do you think theatre, and in particular set design, can get people thinking and start that dialogue?

Coyne: Theatre is an excellent place to have a conversation about our differences and it encourages dialogue. It’s a great medium to bring in a visual sense of the subject. The difference between theatre and film, especially when it comes to set design, is one can be more abstract in theatre. One doesn’t have to be as realistic as film might require, so it gives you license to create something that could generate more thought, particularly on the subject of autism. The story can be more important than showing a specific location, or what a room looks like. This story especially is much more about the psychological. I think scene design can help show that, especially when it takes on a more abstract approach.

Unsworth: After seeing Uncommon Sense, if someone wanted to take more proactive steps, such as continuing learning about autism and educating themselves, what should they do? What’s the next step, do you think?

Coyne: The most important thing anybody can do is to try and find a family, it can be through your church, your community, or even a relative who has a child on the spectrum, spend some time with that child and just learn about them. Learn what they like, what they don’t like. Just try to understand where that child is coming from, or it might even be a young adult or a fully-grown adult. I think if people were to try and do that, just meet one or two people that they may not have had an experience with, it would open up their minds and their way of viewing an autism diagnosis. Uncommon Sense is trying to do that, in some ways, but I think people should pursue it in real life. They will find that the issues any kid is going through are the same that a child on the spectrum experiences, but a lot of times it’s bigger, it’s more magnified.

The interview was conducted by Rebekah Unsworth, an MFA candidate at Pennsylvania State University with a special interest in Theatre and disability.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rebekah Unsworth.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.