Creating art that reflects our time, Kat Mustatea is a playwright and technologist whose conceptual triumphs are rooted in narrative-led, drama. Her creative endeavors pay regard to the bearing of AI and social media on art and society. Among Mustatea’s numerous accomplishments is a STARTS talk at The Pompidou Center in Paris.

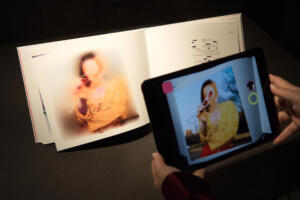

Her augmented reality (AR) book meant to disappear “Voidopolis,” is forthcoming in 2023 from MIT Press/Penguin Random House. It previously won the Dante Prize for art and has been exhibited globally, including at Ars Electronica in Linz, Austria.

A Y6 cohort member of NEW INC—the art and tech incubator at The New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York City, she is a curator of EdgeCut, a live-performance series that explores humanity’s enigmatic connection to the digital. Working when there was no pattern or precedent, her art-making explores hybrid ways of experiencing performance in the age of intelligent machines.

“Rather than ‘style,’ I would reference maybe strategies, or habits of mind. My background is in theater, which I learned by doing when I lived some years in Berlin, and also in theoretical mathematics, which led to a few years of a day job as a software engineer. I stuck to the in-betweens early on, to the peripheries of categories, because I didn’t fit anywhere—and now it’s become a habit of mind in much of my work,”

Mustatea said of her artistic style.

Voidopolis an augmented reality (AR) book meant to disappear. Photo credit: Kat Mustatea + Process Studio.

Moving now through terra incognita, her cross-disciplinary masterworks evade categorization. On developing a medium and its potential, she continued, adding,

“The heart of what I do is drama: I’m rooted in narrative-led, live performance, which is then in some way mediated by technology. As my stories develop, I begin to push against the constraints of a specific genre and medium and often end up building my own scaffolding for the format the story needs. My friend and colleague Toni Dove calls it ‘writing the song and building the piano at the same time.’ Which is how I find myself working across genre and across media frequently. But that habit of mind—of creating a bespoke, formal scaffolding for a story—boils down to the sense that form IS ALSO part of the meaning of my work. It’s a signal that meaning is embedded in the formal presentation as much as in the narrative. So, asking: Why was the story told in this medium, this format? How does the format contribute to the overall meaning? What does this medium mean? My current project is literally building an instrument that doesn’t exist, while simultaneously figuring out how to compose with it,” said Mustatea.

The uncanniness of her art lies in the sense that there are two worlds—one of the seen and one of the unseen.

“Yes, I think you pinpointed it. Underlying most of the worlds I make are hidden rules that lead to peculiar behaviors, motivations, outcomes.”

She continued, adding,

“The storyworlds in my plays include: people turning into lizards, a woman has a sexual relationship with a swan, a one-eyed cyclops who lives in Manhattan tries to fit in by seeking plastic surgery to have a second eye implanted in his head. For years, people would tell me: ‘This script reads beautifully, but I don’t have any idea how to stage this.’ The lightbulb moment for me came from realizing the kinds of uncanny stories I’m drawn to are native to cutting edge technology, which is as uncanny as it gets. The modern world, in particular its technological innovations like AI and mixed reality, are bonkers and unreal, and many of them mess with our synapses and our ability to relate to one another, in increasingly absurd ways.”

Lizardly is a live, mixed-reality play created by Kat Mustatea and Heidi Boisvert.

Lizardly explores the impressions of AI, environmental collapse, and inter-specialty. Photo credit: Maria Baranova.

“I think of the internet as this vast ocean of flotsam and jetsam, a mess of things mostly profane and dissonant, with maybe a few spots of respite and awe. Isn’t that what modern life is like, too? If the job of the playwright is to hold a mirror up to society, as Shakespeare did in his own time, then how do you reflect back all the absurdity and dissonance and irreality that is part of being alive right now? I’m pretty sure we need new formats and techniques for live narratives. That’s what I’m after. That’s my project,” expounded Mustatea.

Connecting the spoken language with that of movement language, her staging employs digital and physical formats including virtual reality (VR), motion capture, and machine learning. The form and essence rendered transport percipients into a universe of vast potential.

“The other thing, fundamentally, is that I’m fond of misusing pieces of technology for purposes they weren’t intended for. It’s a form of subversion, but there’s also a formal delight to it. Discovering new terrain in what was perceived as already fairly well understood. Just being able to turn things upside down and wreak havoc with everyone’s expectations—and along the way get people to see things in a new way. Working with new technologies is a way of developing a medium in the contemporary moment, the potential of it, but also, fundamentally to comment critically on technology itself. Who else but artists are going to comment critically on the tools and tendencies that societies enable? It’s literally our job as artists to do more than just entertain. Nothing wrong with entertainment, but we have this mighty mirror we might hold up to society, and maybe by doing that we might change some minds once in a while,” said Mustatea.

The augmented reality (AR) book meant to disappear, Voidopolis. Photo credit: Kat Mustatea.

Striking a balance between passion and caution, her mixed-reality plays delve into the collective imagination. Themes of moral reflection and the meaning of machines making art prevail.

“And I’m also interested in emerging genres, like mixed reality drama. When my collaborator and I created Lizardly, we weren’t the only ones to have made a mixed reality play. The pleasure is in discovering the affordances of a novel medium, working out how to make such a medium truly theatrical, rather than a work that is still so beholden to the technology that it feels like a tech demo. Mixed reality theater is a specific emerging genre I find exciting because all of its possibilities haven’t been fully understood, and there’s still rich formal ground to be staked out.”

Building upon a “Digital Dozen” prize awarded by the Digital Storytelling Lab at Columbia University School of the Arts and a group show at CultureHub at LaMama in Manhattan, Mustatea comments on her body of work—a lens through which to think about the inclinations of new technologies.

“Everything I do starts with language and with story, and the stories I end up telling are the ones I can’t get out of my head. I was very deeply drawn to the mythological stories I learned in grade school; they are not bound to literal events or reality, and for me they get to some deeper, emotional part of human experience. Mythology is a way of organizing emotion. Earlier, these were the Western, Greco-Roman myths, but more recently I’ve delved more deeply into East European mythology and folklore. These speak to me even more authentically because I am from that part of the world. I usually home in on a theme I already resonate with or which feels like part of the cultural moment, but then I try to find space inside any given myth for myself, for my specific, more personal experience. So many folklores and myths come with suspect assumptions about gender and social norms, and those deserve to be criticized, reconfigured and re-imagined, rather than taken at face value. Eventually, the original myth fades away like a casing or cocoon, and I end up with a narrative that feels opalescent with the sense that it belongs to me—but also, hopefully, can reach beyond me to grab someone else by the heart, too. That sounds hokey, I know, but if the beating heart of some raw human situation is not there in any project I’m making, then all the technology and theatrics are for nothing. I mean, there’s nothing wrong with spectacle, but I need to be doing more when I’m making work. I have too many opinions.”

Voidopolis. Photo credit: Kat Mustatea

“Pretty much everything is legitimate as inspiration. I’m not precious or high-minded about my influences. I’ve read my cannon, but I also care about obscure pockets of pop culture. Kafka’s Metamorphosis and the TV show ‘Bojack Horseman’ both enlisted human-animal transformation as a way of talking about the utter preposterousness of what it means to be alive right now. There’s also a lot of rich material for me in gaps, failure, and constraint,” said Mustatea.

Augmented reality (AR) book, Voidopolis. Photo credit: Ars Electronica.

As emergent technologies are transforming every aspect of human endeavor, Mustatea reflects on the interactive experience component in her art, highlighting the significance of “Voidopolis.”

“Voidopolis is an augmented reality book made to disappear. It is forthcoming from MIT Press/Penguin Random House in August 2023 and will be published alongside a bespoke AR app. The images and text you see in your printed book are garbled—created by a milky-looking algorithmic decay process that is meant to evoke the way memory decays over time. You can read the book’s contents through the AR app, but only for a limited time: eventually the digital components also decay, and you are then left with the unintelligible book, a leftover artifact.”

She continued, adding,

“The project is an enactment of loss. The narrative is a loose retelling of Dante’s Inferno informed by the grim experience of wandering through NYC at the height of a pandemic. Instead of Virgil, my guide through this modern hellscape is a sarcastic hobo named Nikita. Although the AR format is typically thought of as an additive process—literally, a layering on of reality—this particular use of AR is deliberately subtractive.”

Voidopolis. Photo credit: Kat Mustatea

Voidopolis. Photo credit: Kat Mustatea

“Something else about the AR format: all the books in circulation reset each year on July 1st, and then gradually the process of decay begins again over the course of the following year. Reading is a solitary experience, but this yearly periodicity means all readers everywhere are witness to the same decay process. It becomes a durational performance of loss across all copies of Voidopolis, each book a mini-stage, that turns the private act of reading a book into a spectacle for a communal audience,” said Mustatea.

Voidopolis. Photo credit: Kat Mustatea

Born in Bucharest, Romania, and based in New York City, the Columbia University philosophy graduate talks about her cultural heritage and the theatre company she founded in Berlin.

“I am American, but immigrated with my family from Eastern Europe as a young child. I have absorbed a sense of the immigrant experience and of the outsider, overlaid with the sense of ambivalence of having left behind oppression under authoritarian regimes, but also a rich cultural inheritance. I think a lot about what it means to belong to a place, to have roots; and also to live between worlds.”

“In Eastern Europe there’s a cultural praxis that can best be understood as ‘speaking between the lines.’ It refers to the tendency to rely on all sorts of indirection—metaphor, allusion, allegory, jokes, double meanings—to speak about things that are dangerous to say out loud. It’s a coping mechanism, a response to decades and generations of everyday people living under strongmen and oppressive systems. That is my cultural inheritance, and something I’ve understood as fundamental to how I construct stories and worlds in my work: there is always a subtext and an undercurrent.”

“I spent six years as an expat in Berlin between 2003-2009. Once there, I fell in with some theater people, and I would say my “calling” came into view almost immediately. It was like being thunder-struck. I always knew I’d be a writer, a poet, but dramatic writing was a whole nother thing—turns out the spoken word is fundamental to both my ear and my heart. I wasn’t part of any of the pipelines that led to theater-making, like a degree or connections in the industry, so I adopted the scrappy upstart approach I’d observed in the NYC theater scene. I wrote my first play, then my second, then a third. I just kind of begged, borrowed, or stole what resources I needed and started staging plays. I was supposed to be in Berlin three months but stayed six years. I think you have to be both young and an idiot to do what I did, and I was both. It was the best theater education I could have possibly gotten: it taught me how to focus on the big strokes, do a lot with very little, and in Berlin I had access to masterpieces of the art form that were touring from all over the world.”

Kat Mustatea and the Voidopolis installation at Ars Electronica.

Alongside a cadre of like-minded artists, Kat Mustatea is pushing the boundaries of what technology can do.

“NEW INC is the art and tech incubator of the New Museum in NYC. It has been an ongoing source of community and collegiality. Being an artist in NYC is lonely. You don’t have an office you go to. I enjoy having colleagues I can chat with, sometimes about the business-y parts of art, sometimes to just socialize with. More recently I am a member at ONX Studio, which is an artist membership studio for VR/XR artists funded by Onassis Foundation,” said Mustatea.

With an overt connection to cutting-edge technology, performance, and art-making that begins to verge on the surreal, Kat Mustatea is one of the great artists of our time.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexander Fatouros.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.