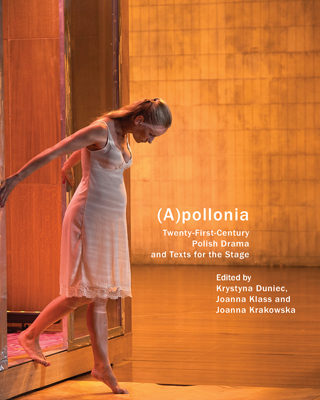

Krystyna Duniec, Joanna Klass and Joanna Krakowska, eds.

Seagull Books, 2014

In her Preface to (A)pollonia: Twenty-First-Century Polish Drama And Texts For The Stage Joanna Klass provides this anthology with a grand mission statement: the dramas, in which Poland becomes the international everyman, are to “resonate with a global readership.” Published in English—the “most international language we have now”—its other stated goal is that “the plays collected in this anthology aim to break stereotypes about Polish people, history, culture, and expose the contradictions of the national psyche.” The first goal, finding the universal experience, may be easier than the second, which demands asking: What is Poland? What was Poland? Where is Poland going? Who is Polish? For many Westerners, Poland was frequently as alien as the surface of Mars. Is it still?

The anthology is organized into four groups: “Polin” with two dramas about the Holocaust; “Transpolonia” thematically linked to post-World War II German-Polish relations; “Postpolonia” deals with the post-1989 transition from communism to capitalism and democracy through the complicated use of the politics of the body and physical identity; and lastly, “Lack-of-Polonia” confronts the move to free-market capitalism and globalization with its attendant social and domestic tensions.

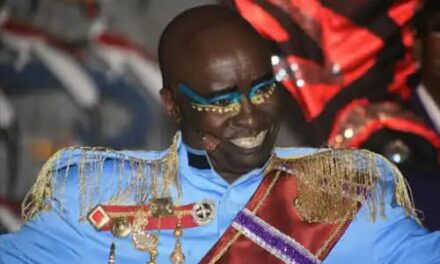

The first two plays, (A)pollonia by Krzystof Warlikowski, Piotr Gruszczyński, and Jacek Poniesyałek and The Mayor by Małgorzata Sikorska-Miszczuk are collected in “Polin,” the Yiddish word for Poland. Both plays examine war from many perspectives.

The Mayor has two parts; the first concentrates on a crime that occurred in a Polish village during WWII and the second shifts to “abroad.” The mayor would like the townspeople to confront this crime but they prefer to forget about it. “Do you want the guilty to perish alongside the innocent?” In war, there are killers and the killed, and in peace, there are the killers retired and their children.

By contrast, (A)pollonia is a sprawling historical narrative ranging from the Trojan War to contemporary writers. Reflecting on the war, Agamemnon looks at the war with a chilling detachment:

[…] The conflict with the USSR lasted from June 22, 1941, at 3:00, until May 8, 1945, at 23:01, which adds up to 3 years, 10 months, 16 days, 20 hours and 1 minute, or 46.5 months, or 202 weeks, or 1,417 days, or 34,000 hours, or 2,040,241 minutes. For the program known as the Final Solution, we’ll use the same dates. That results in 572,043 people killed per month, 131,410 people killed per week, 18,772 people killed per day, 782 people killed per hour and 13.04 people killed per minute.

These calculations do not include the first part of the war when the USSR and Germany collaborated. The play draws on texts from other authors, among them Aeschylus, Coetzee, Jonathan Littel, and Hanna Krall, and at times Agamemnon speaks the words of a Gestapo officer: “the only difference between the Jewish child gassed or shot and the German child burned alive in an air raid is one of method; both deaths were equally in vain.” My immediate reaction is one of lip biting—it’s been 70 years, can we start humanizing the Nazis? It forces a serious level of reflection: can we or even should we rethink the people of Hitler’s Germany? If not, why not? The officer continues: “Like most people, I never asked to become a murderer. I would have liked to play the piano.” And in conclusion: “The war is over!” he declares. “We’ve learned our lesson, it won’t happen again. But are you sure we’ve learned our lesson? Are you certain it won’t happen again?…If you were born in a country or at a time not only when nobody comes to kill your wife and children, but also nobody comes to ask you to kill the wives and children of others, render thanks to God and go in peace. But always keep this thought in mind: you might be luckier than I, but you’re not a better person…”

The “Transpolonia” plays are an artistic inquest into Poland in the wider world. Transfer! by Dunja Funke and Sebastian Majewski, deals with Germans and Poles and was first performed by actual survivors who spoke their hearts out in their native languages, often forgot lines, or even changed stories from one night to the next. The shift in Poland’s eastern borders is played out between sets by The Big Three rock band at Yalta.

Following Transfer! is Trash Story by Magda Fertacz which links a Wehrmacht Stalingrad veteran to an Auschwitz survivor, a PTSD-afflicted son who served in Iraq and civilians whose memories are haunted by their experience during these wars.

The third play in this set, Right Left With Heels by Pilgrim/Majewski, addresses the entire postwar transformation of Poland and Germany as told by the right and left heels of a pair of shoes once owned by Magda Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister’s wife. The 60-year journey of the shoes begins with their travel to the east and ends with the brutal beating of their transvestite owner, with xenophobia and general bigotry a constant companion of the journey.

The next group of plays, “Postpolonia” discusses body politics. Foreign Bodies by Julia Holewińska approaches the acceptance (or lack thereof) of transgender identity in Poland. In a non-linear telling, the scenes that happen under communism depict how the transgender protagonist, an anti-communist pamphleteer, is outed to his circle of activists who then ostracize them. Twenty years later, the woman’s grandchild-to-be is illegally aborted for fear that transgenderism could be genetically inheritable. Even in the present day, she is an outcast.

In Desert And Wilderness After Sienkiewicz And Others, by Bartosz Frąckowiak and Weronika Sczczawińska, a young Pole longs for an empire—but one based on co-operation between Poles and Africans. Playing with the notion of solidarity between white Poland and black Africa, race is almost ignored. “You were colonized? We, Poles, were also!” But colonialism is about more than just borders and occupation. When white writers, regardless of their own history, ignore race and its role, they unintentionally cross a line for race-sensitive audiences in America. Translation is cultural as well as linguistic, and to an audience unfamiliar with Poland’s history of oppression the text may not be successful. That said, perhaps the case can be made that Poland can share its experience as a universal experience and this play, in particular, brings an audience in.

Wojtek Ziemilski’s Small Narrative addresses psychic disembodiment in the face of cultural homelessness. It is a short work written by the grandson of a famous performer exposed after the fall of communism as a collaborating agent for the secret police. The ex-informer suffers from uncertainty about the past and future, feeling trapped in his mind and memory. Opposite him plays the narrator, telling of his cultural homelessness, with uncertain footing in multiple worlds. The problem of Polish communist trauma is difficult to translate abroad.

The final group of plays in the “Lack-of-Polonia” segment, No Matter How Hard We Tried by Dorota Małowska, Diamonds Are Coal That Got Down To Business by Paweł Demirski, and I Love You No Matter What by Przymysław Wojcieszek cannot possibly provide a conclusion because they are so immediate as to be lived on a daily basis. They are so prescient that they feel at times more like a documentary than drama. Together, they present the contemporary cultural uncertainty of transformation in the overwhelming age of globalization. For instance, No Matter sarcastically questions the Polish interface with the wider world,

Gloomey Old Biddy: I remember the day the war broke out.

Little Metal Girl: The Cola war?

Tesco and IKEA are now household names and Poles are “not Polish, just European.” The wild collage and confusion of the contemporary era continues in Diamonds Are Coal with the possible end of Polish Catholicism—“prayer and the lottery have failed him”—and its replacement with the religion of free market capitalism, “this new economic system,” and money. Truly, Nova Polska.

This is exactly why I Love You No Matter What perfectly ends the anthology. There is the memory of the trauma of war carried by and embodied in the protagonist’s (Magda) brother, a veteran of Iraq, who wipes his tears with the white and red flag. There is the Western world represented by Sugar Kowalcyzk, named after Marilyn Monroe’s character in Some Like It Hot. But most importantly there is love, and love of life. It is much easier to take blind steps into the unknown future when you have a hand to hold when the blindness is from the light of hope and not the darkness of uncertainty. Thus, because I Love You No Matter What is the play most clearly and openly about love, it is the most hopeful play in the work and leaves the reader with faith in the ability of art to connect humanity. If Diamonds Are Coal That Got Down To Business asks the terrifying question: Why do we act as if we are alive and special? I Love You No Matter What replies that we do it because we have love.

(A)pollonia succeeds in addressing and exploring the uncertainty of times past, present, and future. It is a wide-ranging examination meaning of what it is to be alive in the 21st century. The plays are situated in Poland, but they can easily fit on a global stage because we all, like Poland, are confused. National identities are not weakened today, but they are faced with challenges of plurality and foreignness that deeply complicate them. Many of the problems associated with being Polish in relation to other countries should not be out of place for those wondering what it means to be American, British, Australian, or any of the other English-speaking nations this fresh translation hopes to target.

This post originally appeared on Cosmopolitan Review on June 14, 2014, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Will Harrington.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.