In one sense every play staged is a play for its times. Something about it attracts, provokes or seduces the minds of the living artists who put it on. Books wait on library shelves to be read again, if not in the same way, then at least with the same sentence structure.

Films, paintings, poems – all those things stay much as they were when first created to be enjoyed later on. We can adapt them and update them, but we don’t have to. In theatre, by contrast, every reappearance is a reinvention. Though such reinventions can feel strikingly authentic.

The value of classic drama is built on this paradox: that the only way the voice of the past can be heard is through the tongue of the present, yet there is some irreducible essence of the past in this interpretive rite. Theatre as a dialogue between the living and the dead.

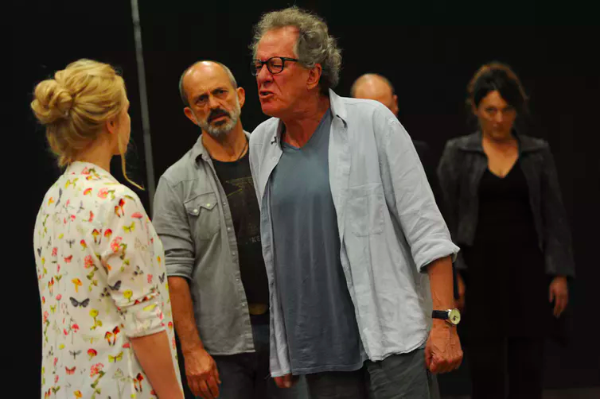

It is in this confronting double sense that some plays feel startlingly fresh, history speaking to the now: admonishing, predicting, pleading, cautioning. King Lear, which is about to open in Sydney with Geoffrey Rush in the title role, is a tragedy that has a great deal to say about peak periods of political destruction.

Lear believes his own propaganda, gets his policy decisions wrong, and goes mad. In his madness, stripped to “unaccommodated man” while a terrifying storm rages around him, he sees his big mistake. He remains an appalling misogynist, blaming women for everything that goes wrong, but he notices, perhaps for the first time, the benighted world around him:

Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this!

(3.4.).

The “this” in the above passage includes empathy with Lear’s poorest subjects, and recognition that his wealth, pomp and power ultimately count for nothing.

How to stage a storm impressive enough to batter sense into a deluded patriarch yet not drown out his dialogue? King Lear is full of such practical challenges. How to stage the Dover scene, in which Edgar cons his blind father, the Earl of Gloucester, into believing he has thrown himself off a cliff? Then convinces him he should base a new found hope in humanity on the “fact” that he survived?

It’s a scene that asks big questions about belief, faith, and theatre therapy. But it is also very hard to present. How should the performer playing Gloucester act his “fall”? What evidence do we need, as an audience, that he really believes he is about to plunge off a precipice?

The AusStage database – Australia’s historical record of its performing arts activity – lists 70-odd productions of King Lear since white settlement, the first in 1837 at Sydney’s Theatre Royal.

In recent years there have been some striking interpretations. The director Barrie Kosky had John Bell as an orange-dildo-waving Lear and Deborah Mailman as a long-suffering Cordelia (1997).

The Shadow King (2013) remade it as a play about the land, the delusion of believing the land can be owned, and the dangers of thinking only of profit. Queen Lear (2012) had Robyn Nevin in a cross-gender version of the title role.

Tom E. Lewis taking on King Lear at the Malthouse Theatre performance of The Shadow King in Melbourne, 2014. Director Michael Kantor dramatically reimagined the King Lear story and set it in a remote Aboriginal community riven by land battles, greed, and distrust. AAP Image/Jeff Busby

Geoffrey Rush is well placed to add to the gallery of maverick Australian Lears. He has twice played the Fool: first for the Queensland Theatre Company (1978, with the late Warren Mitchell as Lear), in a bare-boards production he careened through in Lecoq style; second for the State Theatre Company of South Australia (1988, with John Gaden as Lear), this time as an elderly Fool wielding a joke umbrella which stopped the rain every time he opened it.

On film, his Sir Basil in The Eye Of The Storm (2011) lurches into a chunk of the play during a passing storm.

Now Rush has the chance to inhabit the eponymous role properly. What sort of Lear will he give us? A nihilistic Lear? A manic-depressive Lear? A refugee Lear?

Trevor Nunn once said you have to do King Lear three times before you get it right. Rush’s 30-year journey with the play promises unique insights into this most exhausting and terrifying of Shakespeare’s later dramas.

Philippa Kelly, in her book The King And I (2011), meditates on what it is to be Australian through the lens of encounters with Lear – in the theatre; at school; in a women’s prison; in the wake of Gough Whitlam’s Dismissal; in responding to the devastation of bushfires.

Kelly’s book challenges us to ask what King Lear means here, today. Where is our heath? What is our storm and what does it signify? What is King Lear ultimately trying to say?

Plays are mercurial things. It is the radical instability of dramatic texts that makes them so compelling. They invite active, energetic and strenuous collaboration between playwright and other artists, and the results of this are not predictable.

King Lear is an experience, not an exam question. So it is impossible to offer a neat summary of its meaning. But its mordant images and sonorous cadences throb with dire warning and a sense of imminent catastrophe.

The storm, meteorological and physical, is also mental and emotional and points to the darkest of insights. Buffeted by unwinnable wars and unseasonal weather patterns it is one we would do well to consider ourselves.

For Lear’s tragedy consists in this: that he learns his lesson when it is too late to do anything about it.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on November 23, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Julian Meyrick and Elizabeth Schafer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.