What happens when somebody dies at the frontline? Who’s responsible for getting in touch with their family members? And how do they manage to cope with the sudden loss of their son, brother, father, uncle or friend?

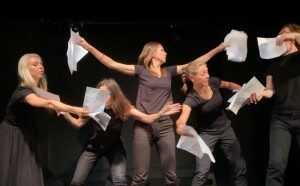

All That Remains is an experience that takes the audience on an emotional journey, highlighting that war demands more victims than those who give their lives at the frontline. Using a clever mix of different performance techniques including storytelling, a capella, theatre, and video projection, the multi-national Molodyi theatre company invites us to fully engage with the individual characters and their emotional turmoil as they try to rationalize what’s happening around them. Based on true accounts from the region as well as the lived experience of the performers themselves, the play allows us a glimpse into different realities of war whilst bringing its many absurdities to the surface; from the lack of purpose felt when coming back from volunteering at the frontline to competing with other people around you for whose grief and suffering is bigger, to the absurd thoughts that cloud our mind when confronted with deep loss.

2019 marks the fifth year of the ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Since its the outbreak in 2014, the war between the Russian military and separatists on one side and the Ukrainian army and volunteer battalions on the other has claimed up to 13 000 confirmed deaths; a quarter of them civilians. What remains of them are the echoes of their last moments bouncing off the bare walls of burned out buildings; their basic details, cause of death, next of kin, etc. collected and neatly put into folders in some government office block; their belongings sent back to relatives together with a letter of condolence.

Amidst this bureaucracy of war, people become raw numbers, just a bit of data on a white sheet of paper; their stories transformed into a challenge to be sorted out. We follow a conversation between two government officials at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as they complain about how hard it is to find casualties’ relatives. “Let’s try and identify them on Facebook, send them a message,” they conclude. The disbelief and pure shock are clearly visible on some faces in the audience. Perpetuating our empathy, the performers begin reading out the names of victims of this gruesome war aloud.

“I don’t know how to talk. I never cried serving three years at the front. Now I cry every day, all the time,” a frontline volunteer states. She was responsible for documenting casualties at the front; inspecting the bodies, which sometimes came in several separate bags, checking them for papers and collecting mobile phones. “They’d sometimes ring, but I never dared to answer any of them.”

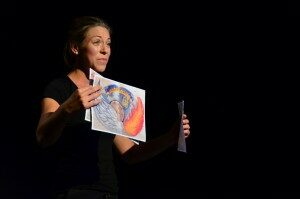

“Meanwhile, a young woman has just received the khaki bag she packed two years ago for her brother. Slowly, she lays out its content on stage: trousers, shirt, documents, pictures, a book, a helmet liner with a hole and brownish stains on it, and a pair of British Army boots that she had spent so many hours to find online. “I guess now you would qualify them as ‘pre-owned’,” she says. As we watch her reminiscing about her brother joining the army, an army that expects its combatants to buy their own bullet-proof vests, we begin to understand that it’s the emptiness that lingers within those who survive that truly remains.

Our own train of tristesse and emotion is broken by the sister going down to the morgue to see her brother for the last time. He wears fresh clothes, boots. “Somebody else could still use them,” she thinks to herself. Looking at her brother’s face she notices something unfamiliar; he’d grown a beard. And in an absurd reaction to the tragedy, she’s facing at this very moment, she shouts out “He looked like f***ing Lenin!”.

War isn’t rational and neither are the emotions and reactions of the people living within it. Throughout the performance, we’re presented with videos from the frontline, “The most interesting thing here are the frozen droplets on the bushes,” the soldier comments whilst giving us a tour around the camp, the machine gun, the trench, where they hide… As an audience of a theatre performance, we’re still able to distance ourselves from what’s happening on stage, the stories being told and the different fates the protagonists face. But when we learn that the videos are real, the soldier is real, and that he’s the brother in the story we’ve been witnessing throughout, then it becomes much harder to be distant, to look away, to not feel the gap that remains.

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on September 4, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Juno Schwarz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.