New Year, new line up of West End stars. This time it’s the turn of Olivier-Award-winner Sheridan Smith and multi-award-winning comedian Romesh Ranganathan, both household names, now appearing in a visually delightful revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s rather dark psychological drama Woman in Mind. First staged at the Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough, in 1985, this, his 32nd work, got a West End transfer the following year. It was his early experiment in using first-person narrative and a subjective viewpoint, but how does it stand up to present-day sensibilities?

Well, it certainly resonates with our current concerns regarding mental health issues. The plot is about Susan (Smith), a desperate housewife married to the emotionally distant vicar Gerald, both living with his grumpy widowed sister Muriel, and suffering because their non-conformist son Rick now refuses to speak to either of his parents because he’s joined a cult in Hemel Hempstead. When Susan knocks herself out by stepping on a garden rake, Bill (Ranganathan), a local doctor, calls an ambulance while she slips into another dimension, a place where she’s enjoying life with a beautifully loving family, a caring and erotically charged husband Andy, affectionate daughter Lucy and sporty brother Tony. This fantasy world is a wonderful compensation for the realities of her arid sexless marriage.

Ayckbourn’s portrayal of Susan’s devastating mental crisis is interesting, and written in an innovative way. All the action is seen from her point of view, so it’s clear that her current relationships are unsatisfying, while her fantasies glow with pleasurable thoughts. For better or for worse, this is not a story with a medical diagnosis so, like Susan, we never really understand why this psychotic breakdown has happened — the garden rake incident is a rather clumsy device. Her collapse is neither explained, nor resolved, and is made more complex by the implication that it has an existential aspect.

The play suggests that middle-class suburban life is so awful for women like Susan, patronized and ignored by their husbands and abandoned by their grown-up kids, that they literally go crazy. Although I find this completely improbable, it is a standard modernist critique of what used to be called bourgeois marriage, and Ayckbourn is excellent at writing excruciating scenes of ordinary people in embarrassing situations, talking themselves deeper and deeper into a social and psychological mess. In this play, both Gerald and his sister Muriel, whose cooking is positively dangerous, are awful people, and even doctor Bill is wildly incompetent.

In a sense, the story is a very sad tale in which Susan’s beautiful fantasy life gradually turns from dreamy paradise into an ugly surreal nightmare. She clearly needs professional help, and she won’t get it from the bumbling Bill. But although Ayckbourn’s sympathies are obviously with Susan, and with any fragile woman, his mixing of comedy with tragedy, farce with a subjective sense of the world coming apart, is impressive, but oddly uninvolving. Her relationship with Rick, who suggests that she herself has always been a horrible person, is underdeveloped. Woman in Mind is technically brilliant, but that doesn’t mean that it connects emotionally. For me, it doesn’t.

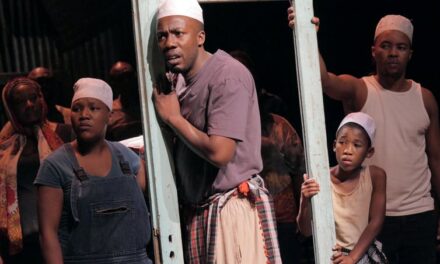

On the other hand, Michael Longhurst’s production has a strong visual impact and is superbly acted. Starting off with a tiny strip of grassy stage in front of a foliage flecked safety curtain, the design by Soutra Gilmour memorably points up the contrasts between Susan’s real life and fantasy world by dressing her imaginary family in bright pastel colours, while her real life has a greyer, more subdued colour palette. The garden set is warmly lit when she is happy and becomes dark and rain soaked as her mind collapses, with Andrzej Goulding’s video projections perfectly illustrating mental distortion and the blurring of reality.

Smith’s performance is excellent, giving us a lonely figure who nevertheless is the smartest person on stage. In her interactions with Gerald (Tim McMullan), Muriel (Louise Brealey) and Bill, she signals her skepticism and unhappiness with a huge range of glances, ticks and subtle smiles. In the scene with Rick (Taylor Uttley) Smith suggests a growing realization that her mothering skills have not been very good, as well as the pain of losing contact with her child. Her sense of sexual and sensual frustration culminates in a finely staged seduction scene when she finally lets her hair down. But by then it’s too late: Smith’s final breakdown is almost unbearable to watch.

Likewise, Susan’s fantasy family are sharply characterized, this time by giving them an exaggerated brightness, with husband Andy (Sule Rimi), who is sexual and kind, daughter Lucy (Safia Oakley-Green), who is affectionate and confiding, and brother Tony (Chris Jenks), who cuts a dashing country-gentleman figure. They are perfect counterpoints to the real family, each of whom nurses their own illusions. In terms of comedy, it is Ranganathan who steals the show. This 40th anniversary staging is a good reminder that, in our current climate of anxiety, a starry West End comedy is a good draw, but also shows how escape into fantasy is futile.

- Woman in Mind is at the Duke of York’s Theatre until 28 February.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.