In a world where so many are escaping brutality, war, persecution, and loss of land, is it possible to tell the story of just one displaced person, and in so doing, tell the story of many? With A Man Of Good Hope, a theatrical adaptation of a biography of the same name by Jonny Steinberg, the Cape Town-based Isango Ensemble suggests the answer is yes.

An energetic cast of over 20 actor-singer-dancer-musicians is shaped by director Mark Dornford-May’s dynamic and lively staging. They take the audience on a journey alongside the play’s central character, Asad Abdullahi, as he is driven from his home in Somalia and across thousands of kilometers through Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Africa.

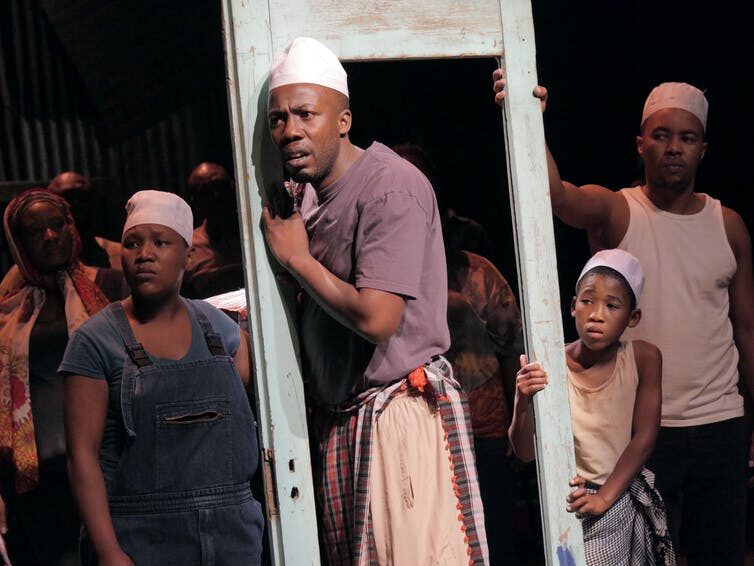

Unfolding over a 22-year period, multiple actors play Asad as a boy, a young man, and as an adult. We first see Asad as a grown man, as Steinberg evidently first encountered him. He is weighed down by life, wearing sadness like a mask.

The performance takes the audience through 22 years of Asad Abdullahi’s life. Keith Pattison

And in the next scene, when we see him as a ten-year-old standing in the doorway of his childhood home in Mogadishu, Somalia with his mother, we understand why.

Virtually overnight, his entire clan, one that knows its lineage across 25 generations, is branded the enemy. Soldiers bang on the front door. His mother is unceremoniously shot.

In a moment, Asad becomes a homeless child from a clan slated for extermination. This is a world where men with guns are everywhere, where anyone can be shot or killed at any time by anyone, where life can be taken on a whim.

After Asad’s mother is murdered, he attaches himself to another survivor, a woman living on the streets. By age 10 he is with her in Kenya at a refugee camp run by the United Nations. There everyone dreams of life in America, a place where “everyone is rich,” “everyone is free” and, in one of the few lines that elicits laughter from the audience, “there are no guns.”

Abandoned a second time by the mother figure he has adopted, he becomes a survivor, a clever street kid, an operator. As he puts it, “I belong to everyone; I belong to no one.”

By the time he’s a young man, he is living in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where he falls in love with a Somali woman who has been subjected to female genital mutilation. After paying off people smugglers, the two briefly end up together in South Africa.

Asad trades goods in a remote black township, experiencing more alienation and persecution, causing his wife to flee the country with their child. But he stays, believing, “I have a better chance to change my fate by staying and fighting.”

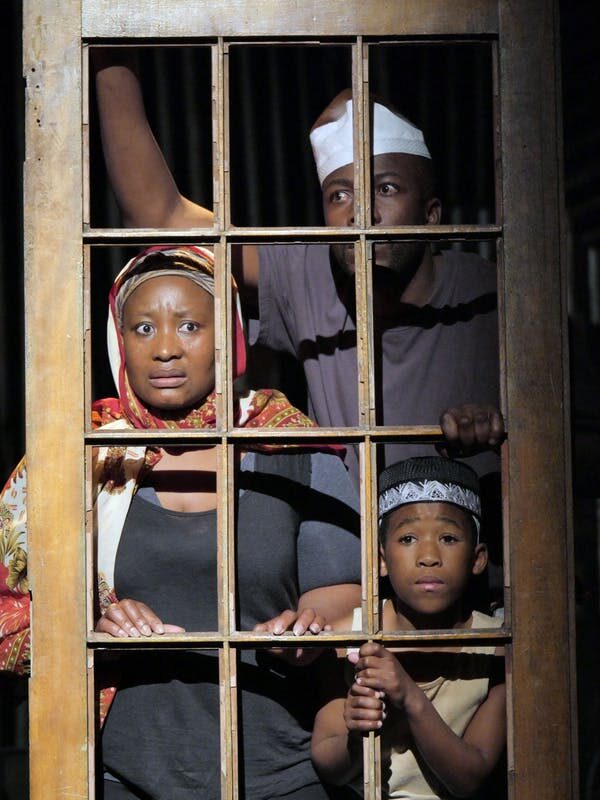

The play’s rapid-fire action takes place on a steeply raked stage comprised of what looks like wooden planks, surrounded by corrugated iron walls, suggesting the world of South African shantytowns.

Props are used sparingly, serve multiple functions, and are sometimes ingeniously transformed, as when, for instance, a door becomes the roof of a crowded bus, held aloft by the passengers underneath, while the boy Asad rides on top in the open air.

A door is used as the roof of a bus in A Man Of Good Hope. Keith Pattison

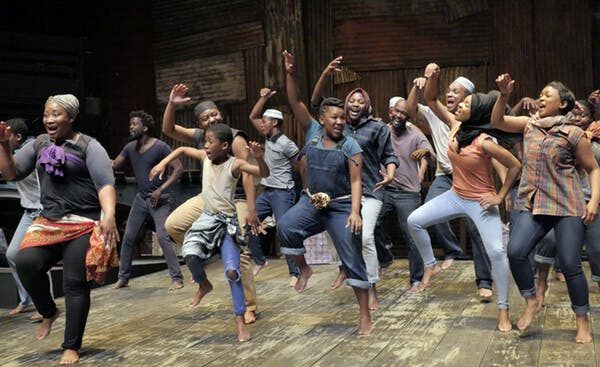

This is a show with much singing and dancing, while many of the performers take turns playing the standing, marimba-style instruments on both sides of the stage. As the predominant orchestral sound, the percussive marimba becomes problematic as it always retains a kind of chirpy, upbeat quality and is not able to deliver many nuances or tonal shading.

The song too was integral to the storytelling, and some of the evening’s most powerful moments were when group choral singing created a huge sound, full of luscious, rich harmonies. Less successful were some of the sudden shifts from speech to song, with many short passages consisting of a single phrase or two suddenly sung in the rhythm of ordinary speech or in a kind of operatic style that came across as awkward or forced.

A Man Of Good Hope is a show filled with song and dance. Keith Pattison

In terms of storytelling, each new tragedy begat another one equally or more horrible, with most of the play’s scenes ending with some kind of dramatic confrontation. While this is no doubt reflective of the trajectory of Asad’s life and parallel to the structure of the book, on stage it can at times feel plodding, even predictable.

Despite these shortcomings, this is a memorable, challenging, high-octane piece of theatre. A Man Of Good Hope is ultimately no tale of triumph over adversity. As the play ends, Asad says goodbye to his writer friend Jonny for the last time, making it clear, despite the well-meaning writer’s protestations, that he has no interest in ever reading his own story.

As Steinberg himself observes in the program notes, “the story is not for him; it is for others.” Ultimately, it can only be for us, those fortunate enough to have had lives not marked by trauma.

A Man Of Good Hope is playing as part of the Adelaide Festival until March 11.![]()

This article appeared in The Conversation on March 7, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by William Peterson.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.