Wherever it comes from, morality or the aesthetic, the anti-theatrical prejudice is a conceptual vanity, subject to or victimized by theatre, while going through every nerve-end to the dubious heart of drama, which has from whatever beginnings always distrusted the theatre. I’m not merely referring here, with the author living or dead, to a certain protectionism of the text against the depredations of the stage, a tradition extending, at times with egregious vigilance, from Ben Jonson to Samuel Beckett . . . it’s constrained ontologically even before it’s thought, for as Heidegger said of language: “Language itself is – language and nothing else besides. Language itself is language.” And though it’s been institutionalized, so it appears with theatre, theatre itself is tautological maybe, but in the immanence of appearance, theatre itself is theatre, before anything else. (Herbert Blau, 2006)

One measure of theatre’s staying power is less its reception in its day, powerful and protracted as that may be, than its resonances in ours, its currency in the contemporary, what is sometimes called its “long afterlife,” something that moves it beyond museum relics like Egyptian sarcophagi displayed behind glass, an artwork, instead, that lives and resonates across generations, across at least western cultures and, these days, across media platforms.

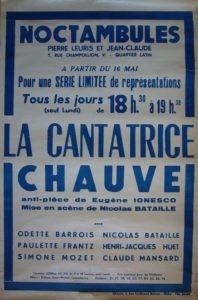

Eugene Ionesco’s La Cantatrice Chauve opened in Paris on 10 May 1950. It was an ill fit for the theater regime of its day, and ours, for that matter, since it was only a one-hour play, so it was put on at 18h and another full-length play was scheduled to follow at 20h. La Cantatrice Chauve, deemed “une anti-pièce” by its author, directed by Nicolas Bataille, is still playing in Paris, 75 years on, 30 years or so after its author’s death, in a theatre named for the street (or alley) where it is located, Theatre de la Huchette.

Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya (1898) was already 100 years old when André Gregory turned his attention to it in about 1990. Gregory’s rendition would never actually open to test its currency but it developed over a four-year rehearsal process with occasional run throughs before small groups of invited guests of 10 or so friends who shared the stage with the actors, what today we might call immersive theater, although such intimacy between audience and actors was a feature of performances at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. For Gregory’s Uncle Vanya there would be no playbills, no newspaper ads, no reviews for the live performances – if performances is the right word – none of the machinery of theatrical production came into play before the filming, which needed financial support. It was created as a learning experience for those involved – a workshop, exercises through which actors and directors, among others, made discoveries and grew – to further understand themselves through texts by others, often out of time. Their Vanya, became, after four years’ work, Vanya on 42nd Street, through which Gregory extended many of the insights he recounted to Wallace Shawn in the film called My Dinner with André, principally his work with Jerzy Grotowski in his “paratheatrical” exercises, theater neither as entertainment nor storytelling, but an event in and of itself; that is, performances that do not point outside themselves, that are not transparent but translucent, at times opaque. The process is the show.

Grotowski had invited Gregory to come to Poland at a time when both directors were doubting the efficacy of theatrical art, moving toward spontaneous, anti-theatrical events. As Grotowski.net explains of Gregory’s involvement with the Polish director (2021 edit):

Gregory was one of the most significant and most active participants at the 1975 University of Research of the Theatre of Nations held in Wrocław (Ule [Beehives] created together with Gabriel Arcand and Małgorzata Dziewulska, 25 June; an open meeting led by Grotowski, 29 June). Following the dissolution of The Manhattan Project in 1976, he began his own investigations and experiments within the Laboratory for Theatrical and Human Research, where the creation of performances was not the primary objective. Together with his wife Mercedes [Gregory, known as “Chiquita”], he participated in the 1979 film Vigil and also created a film about the work of the Gardzienice Centre for Theatre Practices.

In his subsequent American work, Gregory made a pact with his actors for the Vanya experiment – or experiments since the work took various shapes and arcs through its four-year rehearsal process – never actually to perform the play as a play, as a competed artwork, but to show a process. The group spent four years in workshop rehearsals with only slight variations in the cast, mostly improvising around Chekhov, the actors living the play in an abandoned movie theatre – Foxwoods Theater on West 43rd Street – which setting echoes Chekhov’s crumbling, poorly managed, under-maintained country estate. He would take a similar approach to Ibsen, although the setting would become a more traditional, Victorian, suburban home rather than a neglected and decaying theater, which work became his 2013 film adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder. This production workshopped for 14 years with what was Wallace Shawn’s retranslation and in fact reshaping of the drama before it became A Master Builder – that is, A rather than Ibsen’s The Master Builder – in director Jonathan Demme’s film version. Some of the exercises in these multi-year rehearsals involved Gregory’s entreaties to the actors to bore him – repeatedly. Less an off the cuff comment than a theatrical strategy, boredom is a dramatic technique for Gregory, and part of the “long rehearsal” strategy, which is also part of a philosophy of theatre, as he told Rob Weinert-Kendt in an 2020 interview with American Theatre magazine:

A long rehearsal is like a long marriage or relationship, or a long therapy, right? You reach places where you literally get bored, and you think that there’s nothing else that can happen. “I should get out of therapy,” or, “I should get out of this marriage.” Boredom, to me, is generally a sign that there’s a big shark swimming under the water, and if you’re patient, the shark will rise to the surface. So if you can have the courage to see your way through the boredom until the new thing appears, you’ll have amazing surprises. (Weinert-Kendt, 2020)

But Gregory somehow sees Beckett in terms of such a protracted process, or at least Beckett suggests another kind of shark, which may never come to the surface, or, if it does, does so only after a protracted period of rehearsal and boredom, but, as Gregory explains:

There comes a point where I just can tell that anything fresh that’s going to come out of it [any production] will have to come out in front of the audience, and that there’s nothing more you can find in the rehearsal room. Although I have to add that I’ve done four productions of Beckett’s Endgame, and every time I returned to it I was a different André; I was older, I’d experienced more and gone through so much. The play changed. If I were to do Endgame today, it would be about the coronavirus. (Weinert-Kendt, 2020)

Fortunately, like Grotowski, Gregory has had brilliant, receptive and committed accomplices, collaborators like playwright David Mamet, who adapted the Chekhov play for our time, likewise Wallace Shawn, who adapted Ibsen’s The Master Builder into one version of the egomaniacal architect, Shawn’s in something of a narcotic fantasy, and filmmakers Louis Malle, at first part of a select audience but who moved from spectator to collaborator and eventually agreed to film a set of rehearsals in his brilliant cinéma verité, documentary style as Vanya on 42nd Street (1994), and Jonathan Demme. Malle had worked earlier with Gregory and Wallace Shawn (Vanya in Chekhov production) on their collaboration, My Dinner with André. The Chekhov film is much more than a single moment frozen in film-time, however, because Gregory demanded over 12 run-throughs by the actors as part of the filming process. At one point, in a “boring” monologue, Dr. Astrov (Larry Pine) muses about what people will think of “us” 100 years from now, as Gregory’s production occurs roughly 100 years after the play’s premiere, of closer to Chekhov:

Astrov: I sat down and I closed my eyes and thought: One hundred years from now. One hundred years from now: those who come after us. For whom our lives are showing the way. Will they think kindly of us? Will they remember us with a kind word, and, nurse, I wish to God that I could think so.

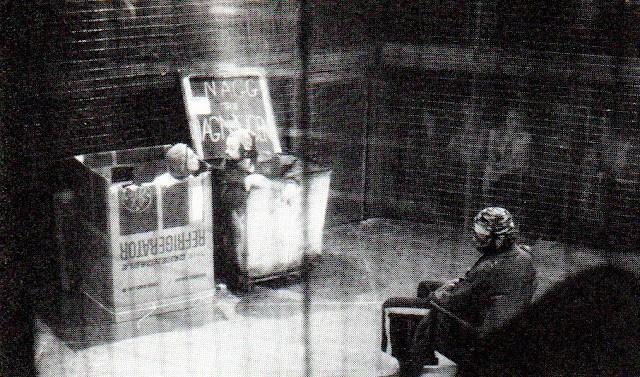

Is Astrov here actually addressing Marina, since Chekhov’s “boring” conversations rarely connect with others in his own time, and his meditations on life and death, on physical deterioration, on success and failure, on a doomed future could easily anticipate Samuel Beckett – Endgame in particular, or his later, starker, posthumous dramas, Play or Not I, or even Ohio Impromptu, among others? The real drama in Chekhov, Gregory understood, in what might be an echo of Beckett, or Grotowski, or something he learned from both, is what it feels like to live, and Gregory brought that same sensibility to his productions of Endgame with his Manhattan Project in a residency with The Public Theatre in 1973 and his continued return to the play about every decade. The 1973 production was set in a room with spectators seated in 4-chair cubicles screened off, from the stage and from each other, with chicken wire, creating cube-like cages, the modules distributed around a hexagonal playing area. Nagg and Nell’s respective habitats were not Beckett’s “two ashbins” but a commercial laundry hamper and a refrigerator packing box, the actors constantly improvising with current allusions and popular song. The New York Times described the set as follows on 17 February 1973:

The performances take place in a New York University attic above Ratner’s [a legendary NY Delicatessen] – if you are hungry you can bring knishes [see the opening of Vanya on 42nd Street] up with you – Second Avenue and Sixth Street. The Playing area is fantastic. Mr. Gregory has built himself a strange, bullring of a theater. It is hexagonal, and the audience is on two levels. The audience is placed in cubicles – each holding four chairs. Each cubicle is insulated from the stage and from the world by chicken wire. So you can See the brilliantly lit stage perfectly, but other members of the audience are dim ghosts in a scenic background. (Barnes, 1973, 39)

The eminent Times critic, Clive Barnes, offers his take on Gregory’s approach to theatre, although he apparently is not a detail guy; he misspells Beckett’s antagonist’s name, for instance, as, perhaps, a version of his own, “Clove:”

Endgame is [. . .] capable of many, many interpretations [not so profound, Clive since this is so with any play]. Personally, I expected the Gregory people to tear apart its text, and to present some terribly aggressive view of Beckett. Indeed to do to Endgame what they had already triumphantly done to Alice. These guys, however, know when to stop when they are ahead. Their Endgame is perfectly straight with a few variations on a theme – and perfectly lovely. (Barnes, 1973, 39)

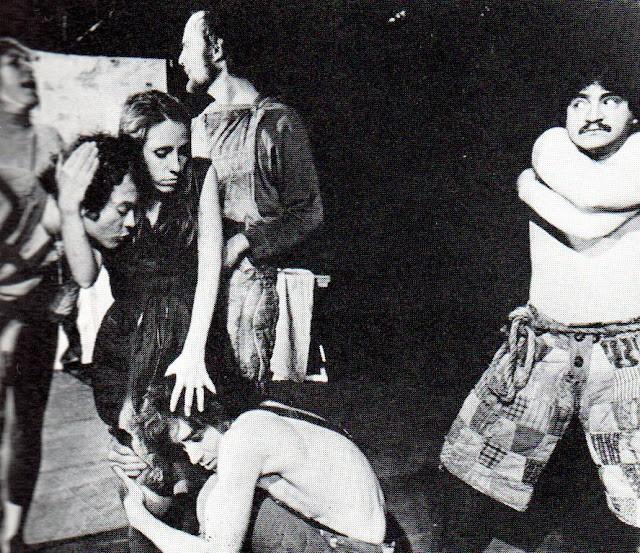

Saskia Noordhock Hegt, Tom Costello, Angela Pietropinto, Gerry Bamman, Larry Pine (kneeling), Jerry Mayer in Alice in Wonderland(1970-75).[1]See Doon Arbus and Richard Avedon’s 1973 book Alice in Wonderland: The Forming of a Company and the Making of a Play. New York: Merlin House.

Writing a review of Gregory’s This Is Not My Autobiography in the Los Angeles Times on 20 November 2020, Charles McNulty, offers a minor variation on Clive Barnes’ comments on Endgame from 1973:

When Gregory was rehearsing a banal translation of Ibsen’s impossibly long [usually some five hours] Peer Gynt he asked [Wallace] Shawn to do a contemporary adaptation. “Wally watched us rehearse for about six months, said, ‘I’ll be back soon,’ and then returned two years later with a play that took place in a New York cocktail party,” Gregory recalled. “And that was our Peer Gynt, which we did at the Public Theater. We’ve been together ever since. Fifty years.”

Gregory, with Shawn now in tow, did his usual textual deconstruction with his variations on Peer Gynt, using again his multi-year rehearsal strategy, as he told McNulty in 2020:

Originally, I did an adult production of Alice in Wonderland that I think played in New York for six years and toured the world. Wally [Wallace Shawn], who did not know me personally, came to see it many times [Shawn says every night]. I didn’t even know that he was a writer or a playwright – I assumed he was a poet. At one point, I needed a writer who could do a modern Peer Gynt and I called Renata Adler, who was a mutual friend, who told me about Wallace. I called him up and he was in a hotel room in the middle of nowhere. He was very excited and sent me about nine unproduced plays and I commissioned him to do a modern Peer Gynt, which played at the Public Theater. That was how we started working together.

My Dinner with André of 1981 was something of an exception in the Gregory vitae, or, like Alice in Wonderland of 1970-75, it became an unexpected hit, as Nathan Taylor Pemberton noted in Bookforum, the online edition of Bookforum Magazine in November 2020:

The making of My Dinner with André reads like a herculean feat of tenacity, one that should put to bed any accusations of dilettantism against Gregory (and Shawn, another progeny of elite New York society). The pair had to scrape together funding, a humiliating experience that required the legendary Louis Malle, who directed the film, to join their pitch sessions to the wealthy. (Gregory’s own father vowed to “never forgive” André after contributing $500 to the project.) It would take Gregory nine months to memorize hundreds of pages of lines [of a script mostly written by Wallace Shawn, but in collaboration with Gregory, of course], which were filmed in twelve-minute takes inside a frigid hotel in Richmond, Virginia. Lacking the funds to heat the space during their winter production schedule, Gregory wore an electric blanket under the dining table and downed shots of brandy between takes.

Much work like that of Gregory is susceptible to travesty or send-up, of course, evident in the action figure scene at the end of Christopher Guest’s film Waiting for Guffman, especially hilarious since, like much of Chekhov and Beckett, there is no “action” in My Dinner with André – short of chewing. It is in that sense decidedly Beckettian of Chekhov, despite the realism of its locale, like Beckett’s short play about breathing, Breath, a play without characters or movement that lasts about the length of a breath, another play in which nothing happens, as Godot has been described, but in contrast to a long film about chewing. And The Simpsons offered its nod to My Dinner with André with a video game in which players can comment on the protracted discussion by moving a joy stick to indicate a set of programmed comments on the film’s grandiose, pretentious chatter, options such as “Trenchant Insight,” “Bon Mot” or “Tell Me More,” all of which punctuate the hyper-inflated nature of the film’s discourse, not unlike Vladimir’s comments on human responsibilities during Pozzo and Lucky’s struggles to right themselves in Act 2 of Godot. But such cultural appropriation is another indicator of art’s sustainability, like the Geico commercial with the newt recrafting Brando’s “Stella” scene from A Streetcar Named Desire, or The Simpsons send up in season four, “A Streetcar Named Marge”, both the “Animation Showcase” and their “Oh, Streetcar,” the full musical performance of the “Marge Animation” – or like the Muppet’s version of “Waiting for Elmo” on “Monsterpiece Theater,” the episode merging two cultural institutions. You’ve got to be renowned to be ridiculed.

In seminars, [. . . Herbert Blau would contend] that “students may engage with a play far more profoundly if they don’t go to a production… the brain is the best stage of all, inexhaustibly ideational, with a repletion of image . . .”. Blau would continue in his seminars to proclaim that the purpose of the Actors’ Workshop was to “save the world,” but he would also insist that “at some level, to do theatre, you also have to hate it.”

This of course reflects the old English department canard that theatre in the flesh corrupts the singular vision of the playwright (or the professor, for that matter). Blau learned it at Stanford from his teacher Yvor Winters, who so despised theatre that he never once made the trip from Palo Alto to his student’s celebrated Actors’ Workshop in San Francisco.

André Gregory’s 1973 Endgame (L-R) Saskia Noordhoek Hegt (Nell), Tom Costello (Nagg) and Gerry Bamman (Hamm) in Jerry Rojo’s set. Barnes notes “incidentally”: “this is one of the best things in the American theater here and now” (Barnes, 1973, 39).

Barnes, Clive (1973). Theatre: André Gregory’s Endgame, The New York Times, 8 February, 39. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/02/08/archives/theater-andre-gregorys-endgame.html.

Blau, Herbert (2006). “Seeming, seeming: The illusion of enough.” Against Theatre. Performance Interventions. Ed. Alan Ackerman and Martin Puchner. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 231-247. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230289086_13.

Rpt. in Blau, Herbert (2011). Reality principles: From the absurd to the virtual. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 103-18.

Kalem, T. E. (1973). “The Theater: Death Is a Cabaret,” Time, 5 March. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,903923,00.html.

Weinert-Kendt, Rob (2020). “André Gregory: ‘The Creative Process Is Very Mysterious,’” American Theatre, 3 April. https://www.americantheatre.org/2020/04/03/andre-gregory-the-creative-process-is-very-mysterious/

This article is part of the report on Between.Pomiędzy Festival 2025, available on TheTheatreTimes.com.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by S.E. Gontarski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

Notes

| ↑1 | See Doon Arbus and Richard Avedon’s 1973 book Alice in Wonderland: The Forming of a Company and the Making of a Play. New York: Merlin House. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “While in residence in Marfa, André Gregory performed Samuel Beckett’s Endgame with a small group of actors, artists, and designers. He also presented readings, talks, and screenings of his influential films My Dinner with Andre and Vanya on 42nd Street. Throughout the week, this series of events celebrated and examined in depth the work of one of America’s most influential and innovative stage directors.

Also participating in the program were long-time collaborators Eugene Lee, actors Gerry Bamman, Larry Pine, sound artist Bruce Odlen, and filmmaker Cindy Kleine [André’s wife]. The program featured open rehearsals of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, a new production directed by Gregory, as well as a one-man performance, After Dinner with Andre, focusing on his distinguished 40 year career in the theatre.” https://www.ballroommarfa.org/program/760/. |