In May and August 2017, respectively, Theater der Welt in Hamburg and The Shanghai Ming Contemporary Art Museum 上海明当代美术馆 hosted Chinese avant-garde theatre group Paper Tiger Theatre Studio (纸老虎工作室)’s performance, 500 Meters: Kafka, the Great Wall, or Images from the Unreal World and Daily Heroism (500米 — 卡夫卡、长城、不真实世界图像及日常生活中的英雄主义).

The show recreates Kafka’s obscure short story “The Great Wall of China” from a trans-historical perspective and reinterprets the author’s exoticized, yet accurate, vision of the symbolic social meaning of the Great Wall in light of the present globalized world. The performance explores the contemporary obsession with gigantic architectural projects as well as the equally gigantic meaninglessness of these huge buildings in the lives of the common people. Director Tian Gebing (田戈兵) takes Kafka’s grasp of the cyclical nature of time as a starting point. He brings out how the political and social ideologies which are carried within the walls of past monumental architecture recur and are reflected in today’s narcissistic structures of power, on a global scale.

500 METERS: Kafka, Great Wall, Daily Heroism and Images from An Unreal World. Courtesy of Paper Tiger Theatre Studio, Krafft Angerer

The artistic concept that articulates the director’s vision of the Great Wall reflects the narrative form of Kafka’s unfinished short story. The configuration of the performance is fragmentary, composed of seemingly unrelated parts that finish abruptly and defy the rules of reason; scenes consist of a mix of narrative bits from Kafka’s text, Chinese classical poems juxtaposed with citations from contemporary literary works, factual references from the lives of China’s great emperors, and interviews with workers at Zhoushan commercial port and dislocated people in the Three Gorges Dam area. This intricate blend alternates with parodies of Chinese model theatre from the Maoist era and of China’s internationally acclaimed show, A Thousand Hands Guanyin.

Just like in Kafka’s text, the performance focuses on the apparent absurdity of having the Great Wall constructed by small bits, with gaps between its sections. By such strange fragmentary design, the centralized power meant to give the constructors and architects of the time the illusion of having a goal – the feeling that their work had a meaning and an end. As clever as this psychological strategy is at inflicting a sense of purpose upon people, it is also, precisely, those very same gaps inside the Wall that display the vulnerability of its bulky construction. They expose its invisible precariousness. Thus, a whole ideology of peremptory power is integrated within the heavy but imperfect walls of the Chinese artificial border – one based on shaky grounds.

500 METERS: Kafka, Great Wall, Daily Heroism and Images from An Unreal World. Courtesy of Paper Tiger Theatre Studio,Krafft Angerer

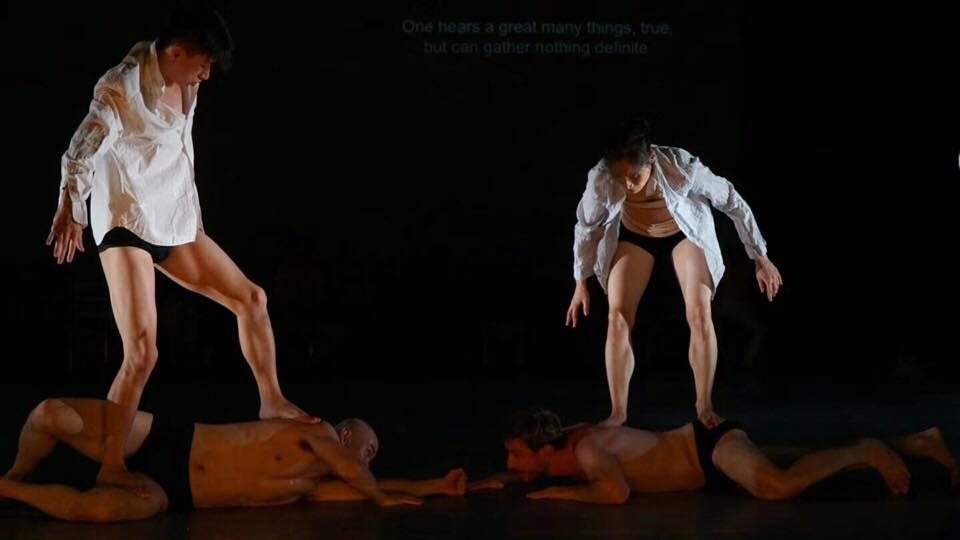

500 Meters moves the aesthetic focus of the performance from politics to raw emotion and turns the former into a pretext for debunking the latter. For instance, the opening scene in which performer Lei Yan walks slowly and staggers on a rolling male body is key to understanding the director’s vision of the emotional symbolism of the Wall. Officially, ‘The Great Wall has become a paradigmatic symbol of China’s historical continuity and geographic integrity’ [i]. It is ‘more than China’s national heritage, it is the global cultural heritage that exemplifies a morally good foreign policy of peace’ [ii]. Tian Gebing doesn’t necessarily choose to challenge this official discourse. He rather emphasizes the other side of the Wall, namely the painful and useless human experience that lies at the heart of its creation process. Human towers, formed on stage by people seating on top of each other, carry the message of the building of the Great Wall. As one of the perched-up performers whispers to another, facing the audience: ‘The news of building the wall has now penetrated the world’. This line, taken from Kafka’s text, recalls the story of a herald trying to carry a message from the emperor, who is on his deathbed, to his subjects. The herald eventually realizes that the distance between the central political power and the periphery is so great that the message would reach the commoners with such delay that it would be meaningless and futile by then. The time-space discrepancy between when the message is sent and when it is received makes the act of governance ineffectual. At the same time, such chronotopic disparities inflict upon commoners the delusion of having a life goal and of needing the message – namely the ideology from the emperor.

500 METERS: Kafka, Great Wall, Daily Heroism and Images from An Unreal World. Courtesy of Paper Tiger Theatre Studio, Qi Rui

All these perspectives charge the Great Wall with tremendous social meaning. As stated, Tian’s outlook shifts the attention from politics to the realm of feelings, tears, and pain: in one word, ‘from ideology to affect’ [iii]. He does so by conceiving the Wall as a ‘non-narrative site[s] of bodily and emotional provocation’ [iv]. The performance is built around the cruelty and senselessness of the workers’ exhaustion and absurd sacrifice for the sake of a political abstract metaphor that never really gets to impact their real lives in a positive way. 500 Meters further parallels the folk poem of Meng Jiangnü — the woman who goes in search of her husband only to find him buried at the basis of the Wall, dead with exhaustion from work — with Bi Nu’s fable, as told in a novel by contemporary writer Su Tong. The only difference is that the novel places the action in a remote Chinese town where displays of sorrow, such as tears, or any kind of feelings are forbidden by law. The human body and mind, upon which the brutalizing political forces act cynically, stand for recurrent tropes of time’s cyclic unfolding. The trans-historical mirroring of two very similar stories reinforces one of 500 Meters’ main apprehensions: that people’s destiny has already been tragically decided.

500 METERS: Kafka, Great Wall, Daily Heroism and Images from An Unreal World. Courtesy of Paper Tiger Theatre Studio, Qi Rui

In defining the meaning of The Great Wall in the contemporary world, as well as the significance of any grandiose architectural project, the Chinese director borrows from the Jewish writer the concept of ‘brick’. Tian circumscribes bricks in their ‘social and kinetic’ [v] understanding as ‘produced through a process of standardization’ [vi], and meant to be assembled with other bricks and stacked into a seemingly coherent social structure. 500 Meters advances this discourse of the human being as a standardized stacked brick and delves deeper into the unperceived complexity of the Wall structure. The performance stages a series of interviews with people working in the Chinese harbour of Zhoushan. The interviewer carries a brick symbolizing a microphone while her movements are juxtaposed with the director’s own voice, as he asks each of the interviewees the same question: ‘Has the news of the building of the Great Wall penetrated the world?’ The answers mix divergent Chinese and Western social voices; most speak in ideological clichés — senseless mottos learned by heart. Among them are voices which – albeit confined – struggle to break with the psychological standardization imposed on them by society’s Procrustes’s bed, only to be painfully muted. They are ‘bricks’ endowed with real articulate thoughts that make up for a complex Chinese Babel of traumatized souls. All of them stand for small individualities, unaware of their colossal role in the making of China’s magnificent history. Dark humour is the main aesthetic means in constructing this scene, through the overlapping of different painful experiences and the characters’ lack of understanding of the full dimensions of their life drama. The sequence brings to light ‘various kinds of internal plurality within China’ [vii], while destroying ‘the myth of a communitarian, monolithic country.

500 METERS: Kafka, Great Wall, Daily Heroism and Images from An Unreal World. Courtesy of Paper Tiger Theatre Studio

The intracultural Babel performed in this scene is expanded into a global intercultural Babel in another scene. The Chinese, Polish, Spanish, and Austrian performers introduce themselves, one by one, in English and Chinese, as ‘Northern barbarians’ on their way to different famous places around the world. This time, instead of isolating China from the ‘barbarian’ invasion, the Great Wall and its fluid and flexible inner structure rather facilitate the mix of cultures and human bonding. The Wall, conceived initially as the demarcation line between ‘civilized’ and ‘barbarian’ worlds, becomes a space for performing the idea of misunderstanding between cultures, which becomes the very premise for their mutual understanding. The Northern Chinese border thus mediates a type of intercultural miscommunication that favors, eventually, the disentanglement of the world’s cultural Babel, and enables cooperation.

The director ridicules China’s ancient infatuation with her own cultural exceptionality and superiority. He also links this historicized belief with the present and pinpoints the East-West cultural interdependency. ‘It is impossible to see Western digital consumer society without China’s mechanical production’, Tian states on the Ming Contemporary Art Museum’s official Weixin page [viii], in order to challenge the local-global dichotomy and the power relation between the two.

Commissioned by the Goethe Institute and conceptualized in cooperation with German dramaturg Christoph Lepschy, 500 Meters glides with rawness and physical stamina through the global spiritual shortcomings of our troubled times. The past and present mirror each other trans-historically; or, better still, the past becomes a prop for recounting a typical postmodern storyin postdramatic fashion, that is, the disease of megalomania and the common people’s ability to ignore and subvert it carelessly, with amazing natural flair.

The performance will take part in the 5th edition of the Wuzhen Theatre Festival in China, in October 2018.

Notes

[i] Rojas, Carlos. ‘Writing on the Wall: Benjamin, Kafka, Borges and the Chinese Imaginary’, 452 F, Vol. 13, (2015), p. 72.

[ii] Callaham, William. ‘The Politics of Walls: Barriers, Flows, and the Sublime’, Review of International Studies, British International Studies Association, (2018): 1-26, p. 3.

[iii] Ibid., p. 5.

[iv] ibid., p. 5.

[v] Nail, Thomas. Theory of the Border (2016), p. 66.

[vi] Ibid., p. 66.

[vii] Ziarek, W. Plonowska. The Rhethoric of Failure, Deconstruction of Skepticism, Reinvention of Modernism,State University of New York Press, (1996), p. 149.

[viii] 纸老虎戏剧工作室500米 — 时间过得越久,一切色彩就越是艳丽的可怕, McaM上海明当代美术馆 (Paper Tiger Theatre Studio 500 Meters – The Further Back They Are in Time, the More Terrible All Their Colours Glow), https://mp.weixin.qq.com/, accessed 30 October 2017.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Andreea Chirita.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.