It’s a cool January afternoon at a bus terminal at Yuen Long station. A blue minivan pulls up. Crammed in the back are Anita Jack, managing director of the Golden Dragon Museum, Daniel Beck, vice president of the museum, and Ben Devanny, from the Bendigo City Council, along with their translator, Heidi Yeung. They have traveled from Australia to the hamlet of Pak Sha Tsuen in search of a dragon maker.

The Australians seek a maker to create a dragon for the City of Bendigo. This dragon, Dai Gum Loong (Daai6 Gam1 Lung4, 大金龍, “Big Golden Dragon”), will relieve the retiring Sun Loong (San1 Lung4, 新龍, “New Dragon”) and continue the 126-year-old legacy of the original Loong (Lung4, 龍, “Dragon”).

The Bendigonians’ quest began years ago with painstaking research and visits to Hong Kong. The search has been challenging, says Jack–dragon makers don’t list ads in the telephone book saying, “I make dragons.” To hunt makers down, Jack and her team have looked into artisan pedigrees, tracing names and shops. They’re going to meet one of the dragon makers today.

The van veers off the highway and negotiates a network of narrow dirt roads before stopping at a large warehouse. An unfinished papier-mache lion head sits outside, painted orange by the mid-afternoon light. Today’s dragon maker, Kenneth Mo, greets the group at the door. Portly and bespectacled, he is not what they had expected. He is young.

Mo, who is one of several candidates being considered by the group from Bendigo, comes from a respected line of makers. He’s in his early 40s, but already has 27 years of experience. His career began as a qilin (Chinese unicorn) dancer when he learned to mend the qilins. After seven years of apprenticing, he opened an incense shop in Tai Po. Soon, he’d branched out into paper goods.

Mo is unusual for the breadth of his work. In Hong Kong, most sifu (si1 fu6 , 師父, “masters”) specialize in creating specific parts of creatures. One sifu might specialize in lion heads and another in qilins. To make entire creatures from head to toe requires space.

“The rarest thing in Hong Kong is space,” Mo says.

We enter Mo’s large workshed. Mythical beasts crowd the space from floor to ceiling. Enormous lotus-shaped lanterns bloom on folding tables. Mo’s children play beneath a flock of paper phoenixes. A dragon’s body with printed scales has been unfurled along the length of the workshop like a psychedelic serpentine rug.

126 years old Loong on a trip to Melbourne in 1901–Photo courtesy

To secure the job, Mo must demonstrate that he has the skills to deliver the dragon by January 2019. A normal dragon, measuring 30 meters, takes three months to assemble. Dai Gum Loong will be over 120 meters.

Jack produces a plastic wrapped object: a scale from the Bendigo’s original dragon, Loong. Made from faded but fine patterned silk and papier mache, the scale is ornately studded with tiny brass fixtures inset with even tinier mirrors. “Too small!” exclaims Mo, examining a mirror. “No, exactly the right size,” says Beck, clear indignation in his voice. Mo digs a long fingernail under a brass fixture and pries the 126-year-old ornament off. With a horrified gasp, Jack withdraws the scale from Mo’s hands.

126-year-old Loong is the world’s oldest imperial dragon. Nobody knows precisely how he arrived in Bendigo, a city 150 kilometers outside of Melbourne, yet there he’s been, his silken flanks glinting with thousands of beads and tiny mirrors, adorned with rare kingfisher feathers, brilliant like a crisp azure sky. Incongruous against this antipodean backdrop, he soon became a beloved part of the collective imagination, delighting crowds to a cacophony of cymbals and drums.

Loong was brought from Foshan by Chinese immigrants who dreamed of striking rich in gold-rush towns like Bendigo. The Chinese did not think it wise to create fanfare around Loong in a climate of hardship and racism. They chose to move softly. Surely their white Australian neighbors would be happy to receive the good fortune and blessings of an imperial dragon.

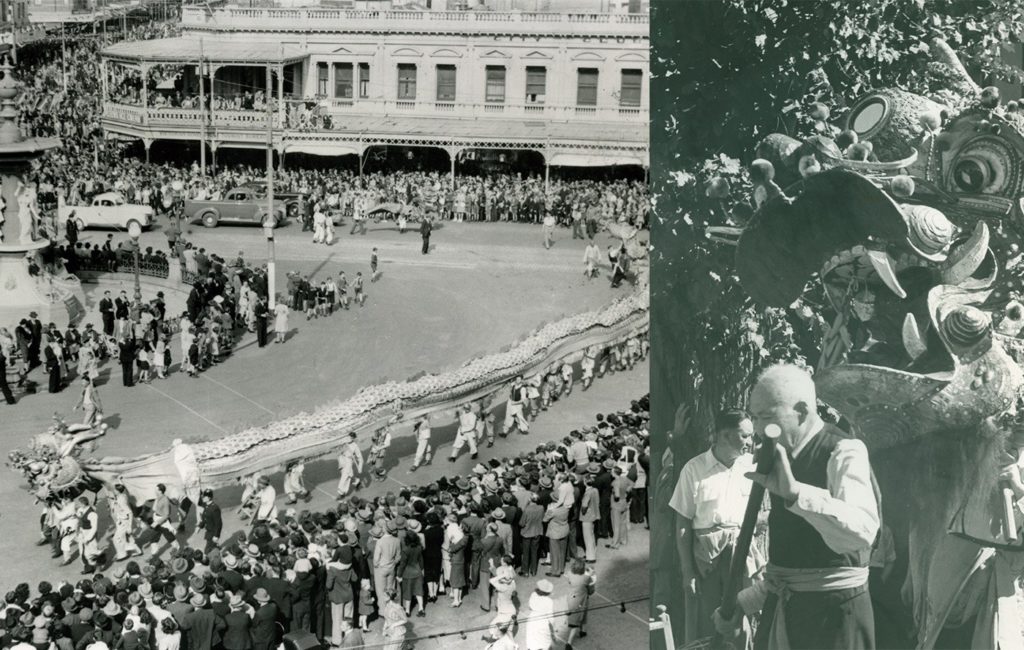

Loong managed to bring people together and to get the white community to support the Chinese–Photos from 1940s and 1930s– Photos courtesy Golden Dragon Museum

Loong first graced Bendigo’s streets at the city’s 1892 Easter parade. It took the Chinese community 35 years to raise money to build the 40-meter-long beast. How long it took to construct him is uncertain; likely it took months, if not years. The splendid dragon soon became an Australian icon. From the 1890s to 1900s, Loong heralded the opening of hospitals in Adelaide, Sydney, and Bendigo. Raising money for the sick and needy he won the hearts of people countrywide. Loong came to symbolize community, benevolence, diversity, and cultural acceptance.

Loong’s warm welcome stood in sharp contrast with the reception Chinese immigrants received at the height of the White Australia policy, introduced in 1901. Against this backdrop, Loong “still managed to bring people together and to get the white community to support the Chinese,” says Jack.

Loong may be the oldest dragon in Bendigo, but he is not alone. The city has a veritable weyr of dragons, including a diaphanous Night Dragon that glows by lantern light, another that floats above the crowds on helium balloons, and Sun Loong, Loong’s successor in Bendigo’s parade festivities.

- An ornate row of hand made scales from Sun Loong’s body. 7,000 of these will adorn Dai Gum Loong – Photo by Billy Potts

- Printed scales of one of Kenneth Mo’s dragons – Photo by Billy Potts

Now Jack unwraps a second parcel. This scale is newer, more vividly colored, but less delicate than Loong’s. This one belongs to Sun Loong. In 1969, Loong retired; the City of Bendigo needed a replacement. The Cultural Revolution had left China bereft of folk tradition. Loong’s homeland could no longer create dragons. Bendigo looked instead to Hong Kong, where traditional paper crafts were alive and well. This is where master Lo On (羅安) created Sun Loong.

Today, Sun Loong is the world’s longest imperial dragon. Originally 60 meters long, he was the longest dragon in the southern hemisphere. But in 1980, a group in Melbourne attempted to oust Sun Loong by commissioning Dai Loong (大龍 or “Big Dragon”), whom they intended to be a few feet longer. To defend Sun Loong’s title, Bendigo raised $30,000 to lengthen him. Since then, Sun Loong’s exact length has been kept secret, but rumor has it he’s between 100 and 140 metres long.

Now the time has come for Sun Loong to retire. The Australians are keen to see if Kenneth Mo is fit to build the successor and to maintain Bendigo’s dracontine legacy.

Loong’s entourage take a break to smoke pipes and pose for a photograph–Photo courtesy Golden Dragon Museum

Sun Loong shows off his impressive train in 2014 carried by a mix of Chinese descendants and people of European extraction–Photo courtesy Golden Dragon Museum

Aside from their cultural importance, the dragons are vital to Bendigo’s economy. Loong and Sun Loong are owned by the city; the Golden Dragon Museum cares for them. Ben Devanny, the Bendigo City Council representative, tells me the Easter parade is the city’s largest event, drawing 100,000 visitors from all over, a majority of whom come specifically to see the dragon. To put this into perspective, Bendigo has a population of 100,000.

Bendigonians rely on their dragons as a major economic driver. All marketing materials for the city feature a photo of Sun Loong; the dragons are synonymous with Bendigo itself. The Easter parade earns the city $20 million a year. It is so popular that visitors must book accommodation more than six months in advance for five consecutive nights or risk staying outside the city.

The city will be pouring $250,000 into Dai Gum Loong. These funds come from the federal and state governments, the Bendigo City Council, and private donations. An additional $500,000 will be spent on costumes and accessories and on restoring Sun Loong.

Devanny, an accountant, is here to keep an eye on how Bendigo conducts its dragon affairs. He must account for restoring Sun Loong, the construction of Dai Gum Loong, and acquiring all the accompanying regalia. He must also factor in airfare and accommodation for all parties involved: the winning dragon maker will visit Bendigo to study Loong and Sun Loong, the Bendigonians need to visit Hong Kong throughout the making process. With all that investment into Dai Gum Loong, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Samples of Mo’s work: a vividly colored sui lun, dragon, and qilin, ready to be put through their paces–Photo by Billy Potts

At the studio, Beck lifts one of Mo’s dragons and stumbles under the weight; the balance is off. Still, Beck has high praise for Mo’s skills: the frame is well executed. He’s unhappy with the materials though. The plastic beading and machine embroidery are not up to standard, and it lacks the mirrors and metal found on imperial dragons. But Beck is nonetheless confident that, with the right materials, Mo might be fit for the job.

Two generations of dragons. Sun Loong (left) and Loong (right) at rest–Photo courtesy

A year ago, Jack met several artisans in Hong Kong. She discovered that many weren’t aware of one another and were unfamiliar with aspects of their shared history. She has since helped connect them, establishing a community to keep the art alive. The chosen dragon maker will be paid handsomely for their work but they will also be paid to learn. In creating Dai Gum Loong, they will revive lost skills through a diligent study of the past. They’ll learn to make dragons, in the Qing style, by examining the museum’s unique collection and reverse engineering the process. Loong is the oldest dragon in the world because of his immigrant origins and remote antipodean home. And thanks to its uninterrupted tradition of folk-art, Hong Kong remains the birthplace of dragons. But in the process of modernization, today’s dragon-making uses new materials and old skills have been lost forever. To complicate matters, Hong Kong’s climate has ensured the demise of every single one of its old imperial dragons. The humidity rots their silk and paper hides. When that happens, these dragons are curled around their heads in preparation for a ceremonial burning, their tattered remains returned to the heavens out of respect.

For the people of Bendigo, burning Loong is out of the question.

“There would be a public outcry: ‘You can’t burn our dragon!’” Jack says.

Beck adds: “There was pressure from the Caucasian community [to preserve Loong]. He [is] too well loved.”

Ultimately, this blend of cultures has delivered Loong from the pyre and saved his kind from extinction. And now Bendigo’s dragons have come to rescue their Hong Kong cousins.

This article was originally written by Billy Potts for Zolima CityMag on May 23, 2018. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Billy Potts.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.