The Queen of Versailles. A New Musical will officially open on Broadway, at the St. James Theatre on November 9th, after several weeks of previews. The show is based on the life stories of David Siegel, the “King of Timeshares,” and his wife Jackie. After Lauren Greenfield’s 2012 documentary film of the same name and several seasons of the television series Queen of Versailles Reigns Again, many people know how this couple, in the early 2000s, took on the construction of the largest single-family home in America – à la Versailles in Florida.

During the subprime mortgage crisis of the late 2000s, construction halted due to financial insolvency. David Siegel was later able to return to the project, which had been under construction for over twenty years.

Lindsey Ferrentino wrote the book, music and lyrics are by Stephen Schwartz. It’s hard to say why the authors needed to bury the American dream, but they succeeded.

In the film, David Siegel explains how he conceived and succeeded in providing a vacation in royal apartments for members of the middle class, thereby realizing their dream of feeling like respectable Americans. Millions of Americans have joined timeshare programs, making David Siegel a multi-billion-dollar fortune. The proceeds were invested both in the expansion of the Westgate Resorts empire and in large-scale projects in other areas of the business. Naturally, David could afford to support a large family in luxury – a wife and eight children from his last marriage alone. Jackie, with whom he had an age difference of thirty years, became his faithful companion, loving wife and mother, businesswoman and philanthropist. Thanks to their union, her American dream of becoming rich and famous came true.

In the documentary, both David and Jackie evoke a sense of compassion, respect for achieving what they wanted, and gratitude for all the good they have done and continue to do for ordinary Americans in need through their social projects and philanthropy.

The musical revolves around Jackie [Kristin Chenoweth], a flighty, selfish, and narcissistic woman who rises from humble beginnings to become one of the rich and famous. She is “fixated” on the desire to become the mistress of the largest house – a replica of Versailles. There she is—Her Majesty the Queen of Versailles, and no one else. Of her children, only her daughter from her first marriage, Victoria [Nina White], and her adopted niece, Jonquil [Tatum Grace Hopkins], are present.

David [F. Murray Abraham] is presented as a background figure with little impact on the storyline. He’s preoccupied with his financial difficulties and has little interest in anything else. He also has a son from his first marriage, Gary [Greg Hildreth], who is also his right-hand man in business. His nanny, Sofia [Melody Butiu], raised all the Siegels’ children. She misses her own family, which is on the other side of the world.

The remaining characters – King Louis XIV and other inhabitants of the palace of Versailles under construction in the suburbs of Paris – were needed by the author of the book to draw a historical analogy. Or, more precisely, to emphasize the similarities between the motifs of Louis XIV and David Siegel, defined by one phrase: “Because I Can.” It’s no coincidence that two musical ensemble numbers— Because I Can and Because We Can —became the first two songs in Schwartz’s music score.

In the musical’s finale, Versailles in Orlando is complete, but all the family members and servants leave, leaving Jackie completely alone. “We just wanted to build the home of our dreams,” Jackie explains from the stage. Her dream, realized, does not feel like a victory, however. The dramatic climax at the end of the second act is the graveyard-like silence of the empty house, surrounding the main character. Typically, in musicals, such moments evoke empathy, as the audience listens to a dramatic aria from one of the main characters. Like, for example, Defying Gravity in Schwartz’s iconic musical Wicked.

In The Queen of Versailles, Jackie’s dream is commemorated with silence. She consoles herself with the thought that Versailles will be remembered by descendants, and they will remember her—the Queen. But everyone understands that they are remembered and respected not for “the biggest house,” but for good deeds, spiritual qualities such as kindness, empathy, and the desire to help those in need. Jackie from the musical has none of the abovementioned… She only has a stubborn desire to become the Queen of Versailles.

It’s difficult to understand the origins of the main character’s “inadequate” portrayal. Was this Jackie’s character as created by the author of the book, or did the director [Michael Arden] and the leading actress [Kristin Chenoweth] have this vision for the character? The main thing was that a dissonance arose between the real character of Jackie and the stage version. It’s worth noting that Chenoweth’s harsh timbre of the voice and childish manner of speaking suited the young blonde bubblehead Glinda from Wicked, but they don’t mesh well with the mature heroine of the musical The Queen of Versailles.

The most complete character is that of Victoria, Jackie’s eldest daughter. Victoria dies of an overdose at eighteen. According to the book’s author, she conflicted with her family and its values, based on excessive consumption. It doesn’t matter whether the story about ideological differences with her mother and stepfather has any real basis. Still, the written life story and musical numbers – Pretty Wins, Pavane for a Dead Lizard, Little Houses, The Book of Random allow the actress [Nina White] to fully reveal the image of a teenager who is uncomfortable in the big world, her own family, and her far from “perfect” body.

Victoria performs one of the most beautiful arias in the musical – Pavane for a Dead Lizard – and touchingly buries the lizard, who died due to human callousness and a basic lack of attention to the vital needs of a pet.

Melody Butiu did a fantastic job portraying Sofia the nanny, perfectly, very close to the real-life Sofia in the documentary. She cares for Victoria and the other children who never made it onto the stage. She says she loves them as if they were her own. But her heart breaks because her own family is so far away. She gives everything she earns to her family, yet their financial situation remains dire.

“Everyone here in America hopes to have what Miss Jackie and David have,” says the nanny. At the same time, she does not envy her rich owners; she treats them warmly and feels gratitude for the right to live with their family and be a part of it.

F. Murray Abraham as David is impeccable from an acting standpoint! It would have been even more interesting to watch him if his character had been “concocted” differently by the creators, if he had more stage presence within the story. In the musical, we meet David at sixty and part with him at eighty, but time has no power over him. A youthful-looking man in an unbuttoned Hawaiian shirt, quite cheerful, leaves Versailles. Where he goes after telling his wife that Versailles was purely her dream is unclear. Both his songs —the solo Trust Me and the duet with his son, The Ballad of the Timeshare King —are expressive, full of character and convincing. However, it’s the lyrics rather than the melody that stick in the memory.

Most of the show’s musical numbers aren’t exactly memorable. And in some cases one can hear a shout-out from Stephen Schwartz and the Wicked score, some melodies within music arrangements, musical phrases here and there, are cameo appearances of some recognizable and beloved themes. It’s a thread connecting the two heroines – Glinda and Jackie.

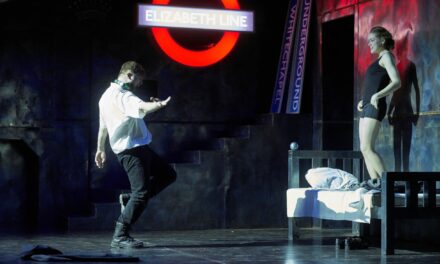

The set design [Dane Laffrey] is quite original. Throughout the performance, the audience sees the supporting structures of the future main hall of Versailles, construction debris, and interior design objects that will one day decorate the living spaces. In the backdrop is a large monitor, periodically showing video installations: interiors, views, close-ups. Neither the screen nor the videos themselves are Broadway-quality components. Only in the final scene does the audience see the Grand Room of Versailles in all its splendor. Probably so that Jackie could descend the beautiful marble staircase. Otherwise, it could have been shown as a photo, and the sets could have been built and used to house the characters in various scenes and proper settings, throughout the two-hour-long action.

Does anyone doubt that a billionaire’s wife can afford expensive haute couture? No. Only in the documentary Jackie wears casual clothes, and at official events she looks impeccable, thanks not only to the good taste of her designer, but also to her model looks. In the musical, Jackie changes from one bedazzled outfit to another, trading one pair of sparkly high-heeled shoes for another. It seems as if the costume designer [Christian Cowan], inspired by Legally Blonde, deliberately orchestrated this parade of tinsel to demonstrate the character’s lack of taste. The high-quality costumes of the French court, clearly claiming historical accuracy, look striking against this backdrop of cheap luxury. As does the youthful attire of Victoria and her cousin.

The idea of timeshares, as well as David Siegel, a significant figure in the timeshare industry, pioneering new business models and actually shaping the market, rapidly growing in recent years through his innovative approaches, appeared devalued in the musical.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the author of the book failed to tell the story of our famous contemporaries – the Siegel family.

Somehow, I want to believe that the creators really wanted to sing, “Hallelujah, American Dream, hallelujah!” but it turned out the way it did—into that said dream’s funeral. I don’t know if the spectators will agree with that concept.

Nevertheless, belief in the American dream has become part of the cultural code of the US population, reflected, among other things, in many musicals, from Show Boat and West Side Story to Hamilton and La La Land.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lisa Monde.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.