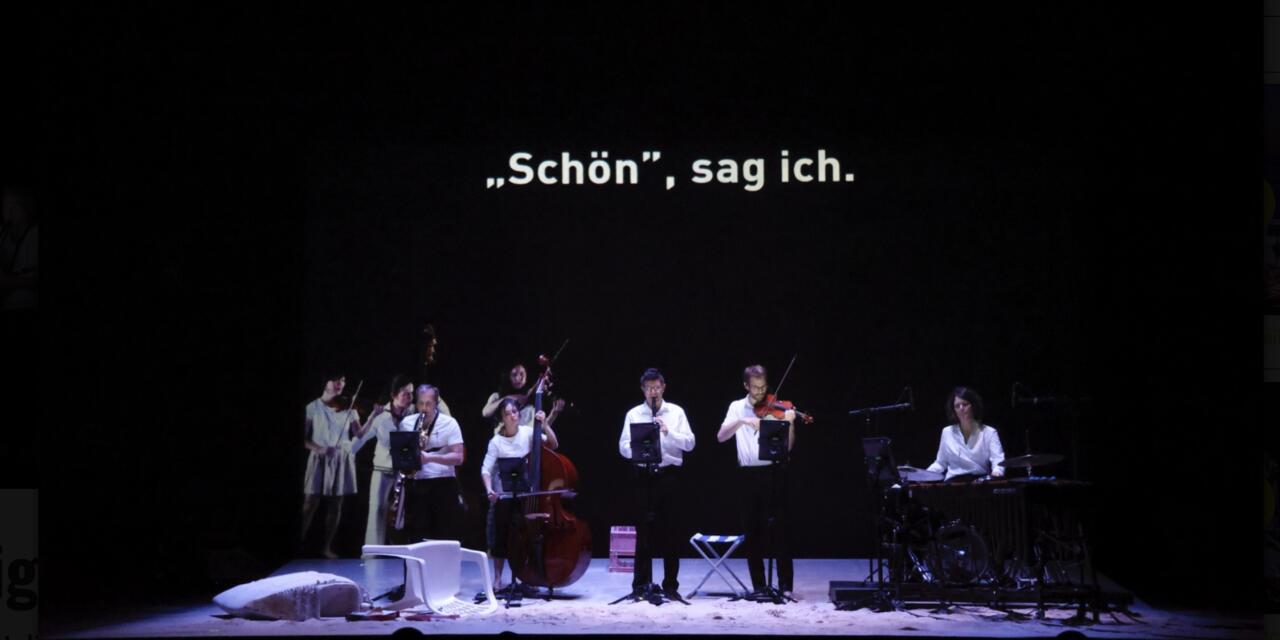

In All Right. Good Night., German docu-theater artist Helgard Haug turns loss into a language. The work interlaces two stories of disappearance — the mystery of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 and her father’s gradual descent into dementia — to explore how humans cope when reason and memory fail.

Presented at NYU Skirball as a part of New York’s Crossing the Line Festival, the piece unfolds less like a play and more like a poem written across air, sound, and silence.

For Haug, co-founder of the acclaimed theater collective Rimini Protokoll, this project marks an unusually intimate turn. For more than two decades, she and her collaborators have staged documentary works that transform everyday people and social systems into living theater. But All Right. Good Night. is her first work to draw directly from her own life.

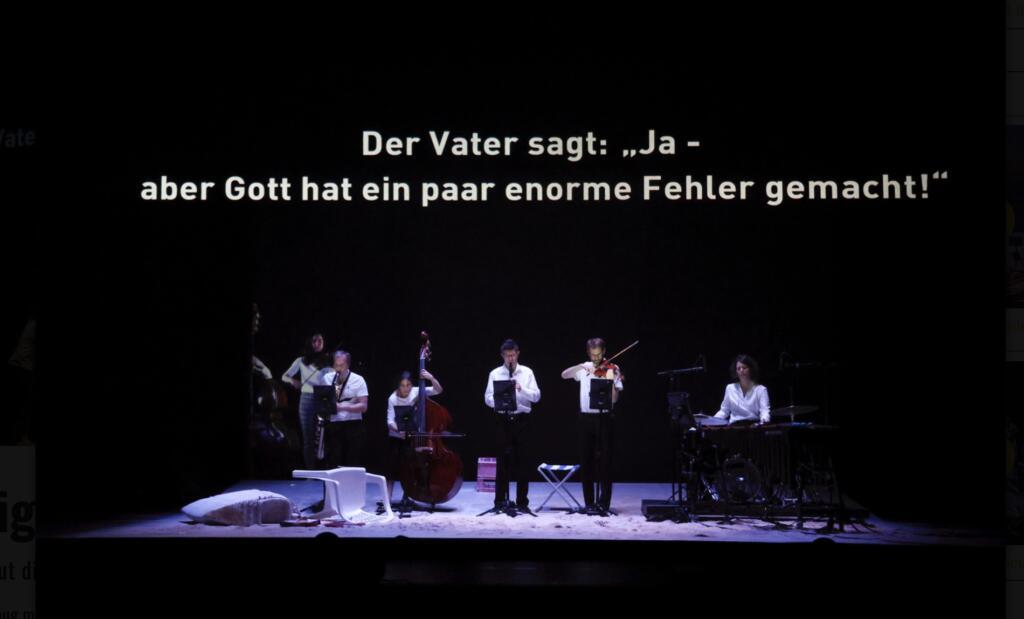

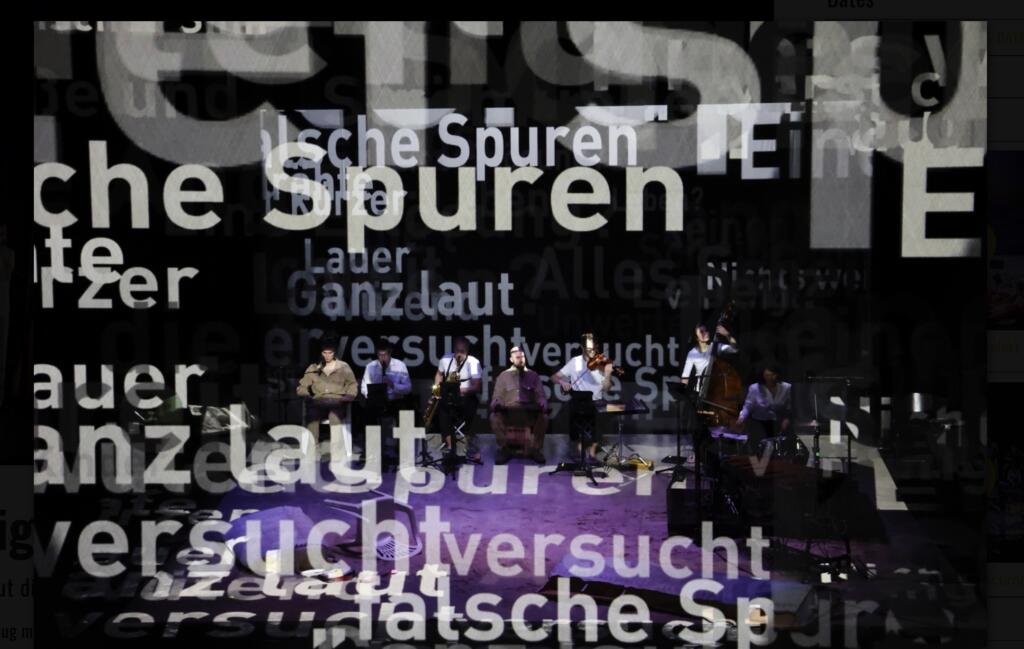

All Right. Good Night., by Helgard Haug (Rimini Protokoll). Part of New York’s Crossing the Line Festival. Photo credit: Merlin Nadj-Torma. [EN: “The father said: Yes – but God made some great mistakes!“]

“It made sense somehow that these forms of not-knowing — of not being able to rely anymore on what you get as information — felt connected,” she said, reflecting on the link between her father’s fading cognition and the vanishing of the aircraft.

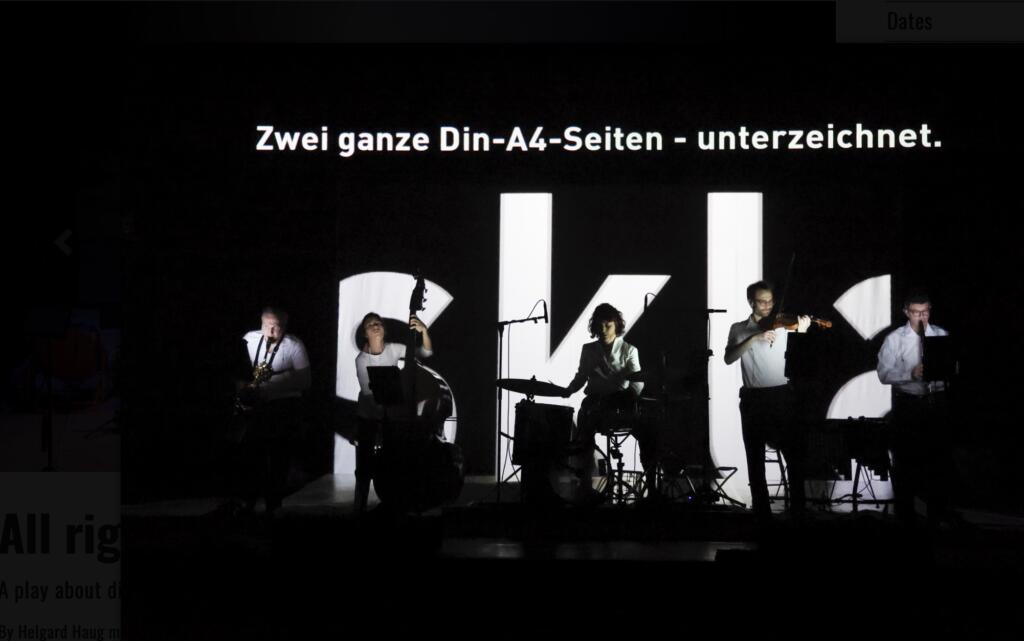

The production’s form is as radical as its theme. There are no spoken words. Instead, sentences appear as projections on a transparent curtain, which separates the audience from the musicians and performers.

Viewers must read the play rather than hear it — translating words into inner voice, imagination, and memory. Haug’s decision was deliberate: she wanted to avoid a performance overwhelmed by personal emotion, and to create distance that invited reflection.

“I didn’t want to describe my feelings,” she explained. “I wanted people to connect with their own. The word protocol became important — it’s a way to state what happens without dictating interpretation.”

All Right. Good Night., by Helgard Haug (Rimini Protokoll). Part of New York’s Crossing the Line Festival. Photo credit: Merlin Nadj-Torma. [EN: “Two entire A4 pages – signed.“]

This self-imposed restraint gives the play its meditative quality. Reading the story rather than listening to it forces the audience to slow down, to experience the disorientation and stillness that mirror the play’s central themes: information slipping away, the mind faltering, the world becoming unreadable.

The silent act of reading also turns every spectator into a participant — each voice in the room reciting internally, privately, together. The text becomes both evidence and elegy.

While language remains sparse, music carries the emotion. The score, composed by electronic artist Barbara Morgenstern and performed by the Zafraan Ensemble, bridges classical and electronic worlds. It doesn’t merely accompany the text — it expands it.

“Normally in theater, music stops when someone speaks,” Haug said. “Here, because the audience is reading, the music can stay on — even be very loud — and the story continues in your own head.”

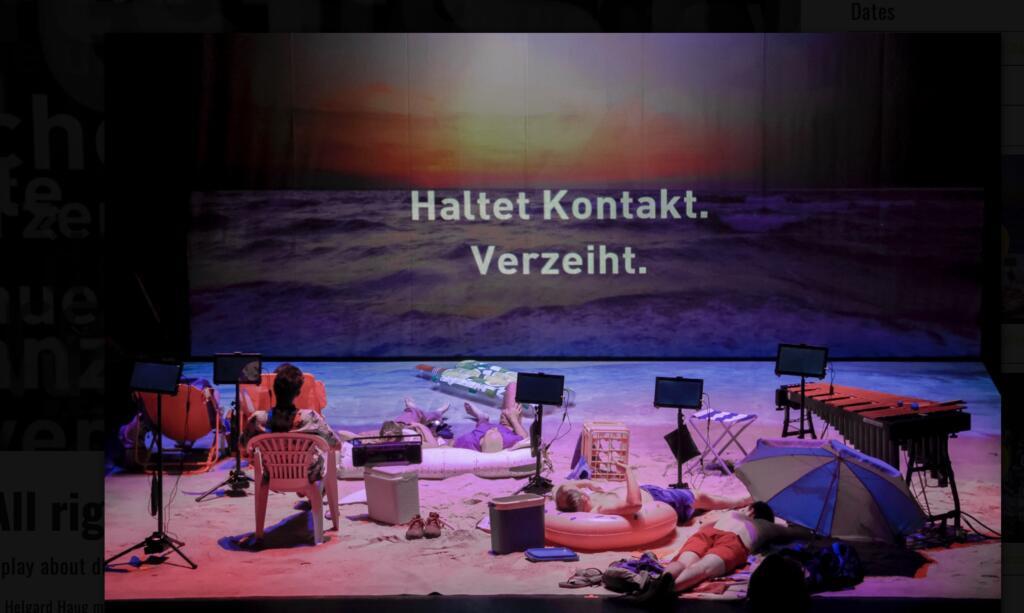

All Right. Good Night., by Helgard Haug (Rimini Protokoll). Part of New York’s Crossing the Line Festival. Photo credit: Merlin Nadj-Torma. [EN: “Keep in touch. Forgive me.“]

The result is a subtle inversion of theater’s hierarchy: sound dominates, while words whisper. Morgenstern’s music swells and dissolves, suggesting turbulence, confusion, and the fleeting coherence of thought.

Fragments of factual reports about MH370 alternate with glimpses from Haug’s family life — her father’s birthday letters to his grandson, the silence that follows when no more arrive.

Together, these threads become what Haug calls a ‘protocol of an irreversible process.’ The lost flight and the fading mind echo each other — both tracing the quiet terror of disappearance, the ache of trying to hold on to what time and chance insist on erasing.

The stage itself becomes a metaphor for that disappearance. The curtain, half-transparent, half-barrier, reminds us that the performers are there, yet unreachable — just like those who vanish.

The audience, bathed in dim light and reflection, sees both the words and its own shadow in the glass. What begins as documentation evolves into a ritual: a collective act of mourning without spectacle.

All Right. Good Night., by Helgard Haug (Rimini Protokoll). Part of New York’s Crossing the Line Festival. Photo credit: Merlin Nadj-Torma.

For Haug, this shared presence is essential. “In this collective act of trying to access something that can’t be explained, we do it together,” she said. “It becomes a kind of shared achievement.”

By inviting hundreds of people to read silently in unison, she transforms the theater into a site of communal introspection — an unspoken chorus replacing dialogue.

Ultimately, All Right. Good Night. confronts the limits of understanding — the point where information fails and faith, or art, begins. It reminds us that despite our technologies and search systems, some things remain irretrievably lost. In those moments, words and music can still gesture toward meaning.

The performance ends not with resolution but with resonance — a quiet recognition that absence itself can be shared. In its fusion of precision and emotion, All Right. Good Night. becomes both a poem and a meditation, and perhaps the purest expression yet of Haug’s theater of reality.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Victoria Zavyalova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.