Ognisko Polskie, the Polish Hearth Club, is an exquisite venue: glistening chandeliers please the eye, red velvet lines the elegant staircases; this quiet haven in South Kensington is full of Old World charm.

Last Saturday night, a traditional version of Chekhov’s play The Seagull was produced here. Set on a lake estate in Imperial Russia, the play was announced by producer Maja Lewis as being about “missed opportunities”– unrequited love, dashed hopes, and disillusionment. It is indeed about the inexplicable misfortunes (petty and great) encountered in life, as well as being a play saturated in human interactions. It’s also worth noting as a work alive with subtext, in which many thoughts and some actions, like the failed Konstantin’s eventual suicide, are implied rather than shown. The Seagull, initially poorly received partly, for this reason, would thus have pleased Aristotle as an imitation of ultimate reality: its ambitions, while not immediately evident, are considerable.

Last Saturday night, a traditional version of Chekhov’s play The Seagull was produced here. Set on a lake estate in Imperial Russia, the play was announced by producer Maja Lewis as being about “missed opportunities”– unrequited love, dashed hopes, and disillusionment. It is indeed about the inexplicable misfortunes (petty and great) encountered in life, as well as being a play saturated in human interactions. It’s also worth noting as a work alive with subtext, in which many thoughts and some actions, like the failed Konstantin’s eventual suicide, are implied rather than shown. The Seagull, initially poorly received partly, for this reason, would thus have pleased Aristotle as an imitation of ultimate reality: its ambitions, while not immediately evident, are considerable.

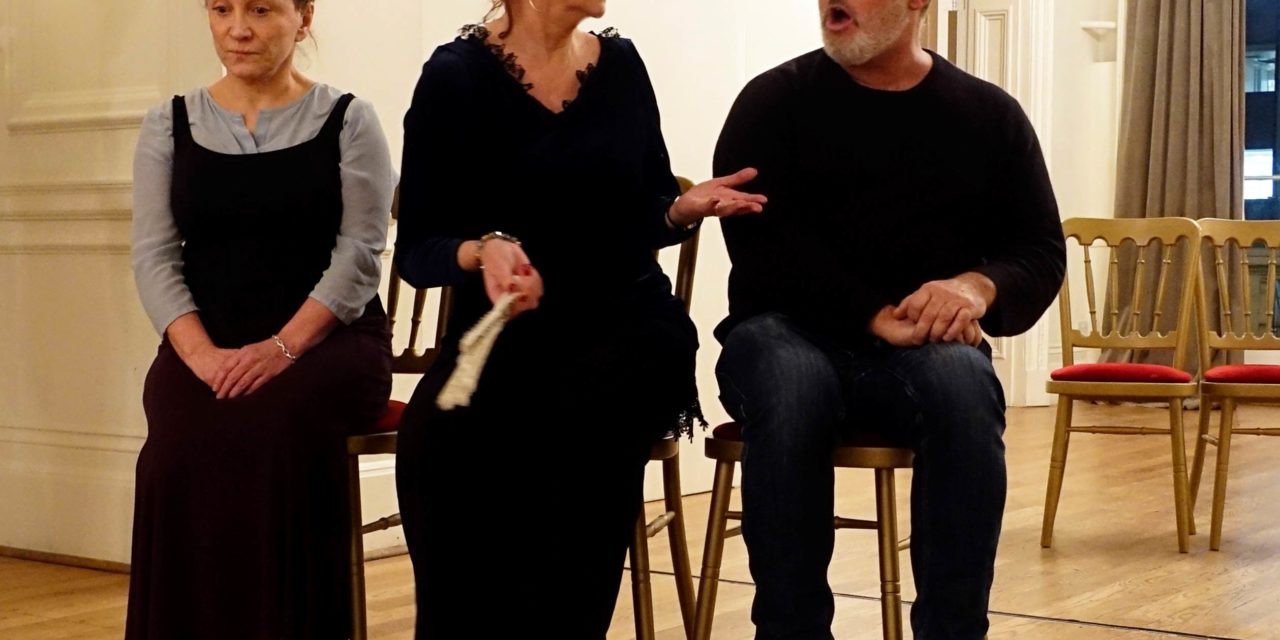

At the outset, the audience was greeted by a unique and lovely set-up, and the efforts of the design team are to be commended. The relatively small space was well exploited by a clever trick of perspective: a smaller stage pushed slightly back, complete with miniature walls and a ceiling, gave the impression of a small sitting room. The addition of tranquil colors and lighting evoked the atmosphere of a lake estate, and the speakers playing the chirping of birds added a degree of subtlety, an attention to detail that heightened the inherent naturalism of the play.

Adam Cunis

Chekhov’s works require patience through their very nature. They’re almost entirely psychological, relying on dialogue and fraught interpersonal relationships, and often in a very domestic way. Some topics, reactions, and episodes can be difficult to relate to for contemporary viewers–such as the trope of the fallen woman.

Yet in its bid to make these themes compelling and accessible, Maja Lewis’s production was, for the most part, a success, and many of the classically trained actors shone, well-suited to their roles. Adam Cunis, playing Konstantin, was not only charming but also believable in a completely naturalistic performance. Jeanette Clark as Polina stood out as genuine and humorous–properly Chekhovian–while Keith Hill as Dr. Dorn’s elfish mimic added subtle believability, delivering the line “Belt up, you old bureaucrat!”–characteristic of this playwright–perfectly. Clark and Hill gave us, as a pair, some of the best comic moments of the evening. A scene displaying the actors’ compatibility was that of Polina’s destruction of the flowers Nina has given Dorn–the instance of jealousy, even between two more mature actors, again heightening the reality of the play. Lynne O’Sullivan must also be mentioned as completely believable in her portrayal of the unconsciously annoying Arkadina. Hannah Keeley as Masha and Maria Hildebrand as Nina had several poignant moments too: one such was Hildebrand’s committed rendering of Konstantin’s woefully idiosyncratic play-within-a-play.

Maria Hildebrand

Yet this production was not without its faults. Despite the strength of individual performances, the necessary strenuous tension between characters proved difficult to achieve (with the exception of the aforementioned Clark and Hill). There could have been more pathos; the microphones could have benefitted from being turned up slightly. Male costumes were much more historically accurate than female costumes, and some moments seemed to drag on–though this is probably due to the nature of the play: Chekhov himself describing it as containing “a great deal of conversation about literature, little action, tons of love.”

Generally, however, this Seagull was an enjoyable experience, particularly for those who can savor delayed gratification.

This post originally appeared on CEEL.org.uk on February 12, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Andreea Scridon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.