4.48 Psychosis, by Sarah Kane, was turned into an opera by composer Philip Venables in a production co-commissioned by the Royal Opera House and the Guildhall School of Music & Drama. While rare to think about the playwright while watching an engaging drama, one can’t help but think about Kane while watching 4.48 Psychosis. It was the last play she wrote before committing suicide at the age of 28. It is remarkable and touching how witty the writing is in 4.48 Psychosis. The audience’s collective knowledge of her suicide weighs on her words posthumously, or at least it did in Venables’ operatic adaption as seen on January 8th in NYC, as part of the Prototype Festival. For instance, the line “I have become so depressed by the fact of my mortality that I decided to commit suicide” does not come off as dry humor, even though the actor read the line perfectly. It’s conceivable the line might have been received more lightly, as would have the body of the play in its entirety if the author did not commit suicide.

As for 4.48, the much anticipated time of day of the play, here are three out of five instances Kane mentions it in the script[i], in chronological order:

At 4.48

when desperation visits

I shall hang myself

to the sound of my lover’s breathingAfter 4.48 I shall not speak again

I have reached the end of this dreary and repugnant

tale of a sense interned in an alien carcass and

lumpen by the malignant spirit of the moral majorityAt 4.48

when sanity visits

for one hour and twelve minutes I am in my right mind.

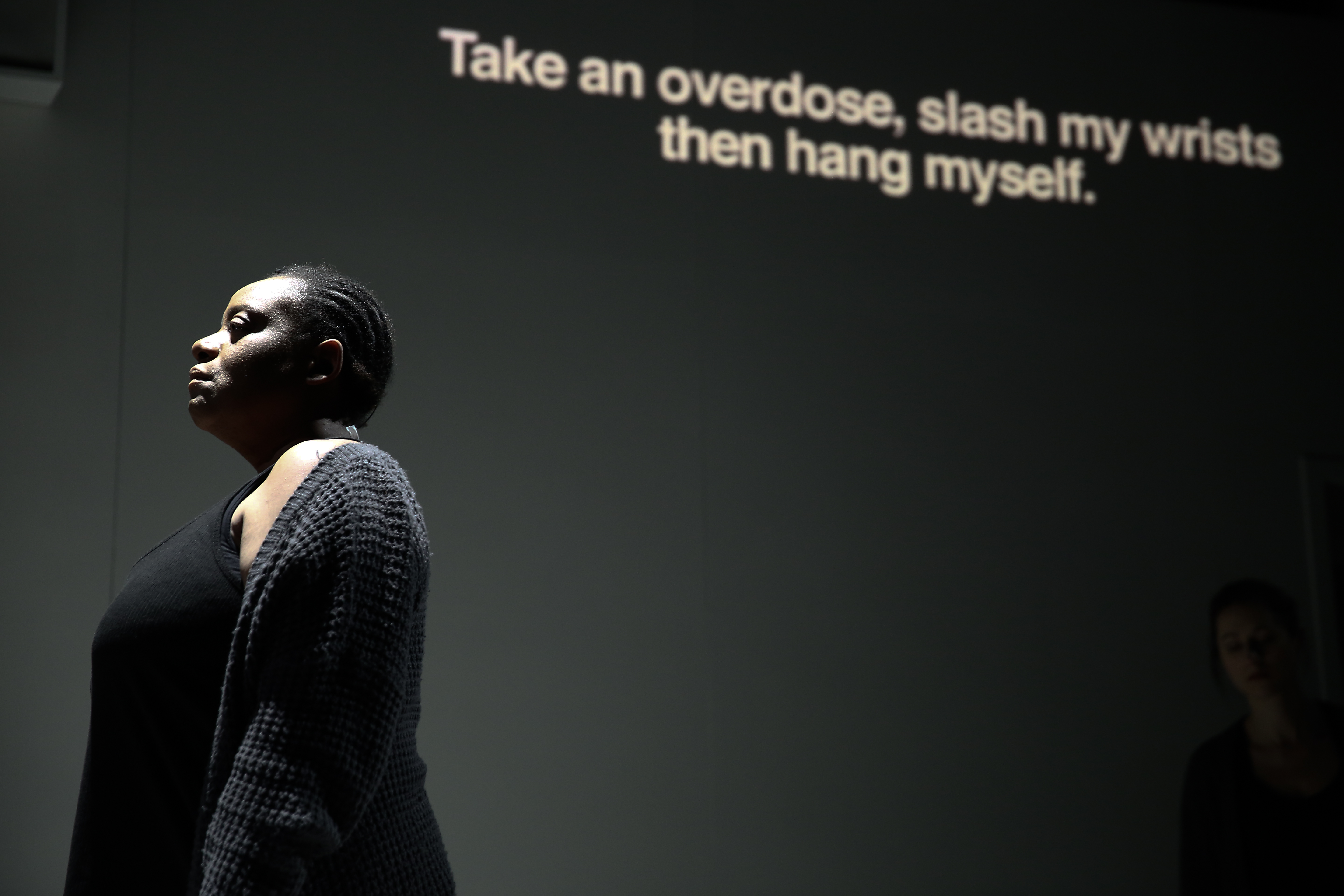

While 4.48 Psychosis, the opera, explores a grim topic, the topic is uplifted by a generous field of inspired, uncanny moments buoyed by music–unforgettable in their originality. Fragments, aphorisms, dialogue, medical prescriptions, even number charts, make up the text of the play. The amount of characters, their genders, who utters what line, and when (if anyone), is up to the cast and director, here Ted Huffman, with the musical composition in mind. For instance, the decision to present the play’s first line “But you have friends” silently as text, projected against the back wall, as music plays, is unexpected and surprisingly unsettling. There are one to six women actors on stage at any time.

The actors all dress in gray shirts and jeans suggesting, as does the all-white, antiseptic set design, they are occupants of a mental asylum. Gweneth-Ann Rand is the central actor. Rand’s character successfully embodies the whole patient, versus the other actors, who play the voices in her head, or, on occasion, the medical personnel that surrounds her. At times, all the actors sing together in a chorus. It isn’t always clear what they are singing about—is it Kane’s text, the processing of raw emotion, news of a Martian landing? The six could be supportive of each other or they could be sinister.

There are two instances in the script of 4.48 Psychosis that Kane wrote down random numbers on the page. The first one:

100

91

84

81

72

etc.

down to 7.

A question while reading the play is how would an actor act recite these numbers to the best dramatic effect…read them highest number to the lowest? Or would they read them by columns as Kane has laid them out? What is the purpose of including these numbers in the story anyways? Did Kane even know or was she truly having a psychotic episode as she wrote the play? In Venables’ adaptation, the numbers are not read by the actors on the stage but projected onto the back wall in large text. The numbers count down, 100, 99, 98, etc. until a number from the script comes onto the screen. The descent freezes to showcase the numbers in the script. The second number arrangement had a slightly different pattern; the numbers skip down to Kane’s pick of numbers in quick succession. Meanwhile, the action of the six characters (perhaps, in search of an author) continues on the stage.

During the presentation of one of these number “scenes”… my mind went curiously adrift to lament how misleading it is to use a number system to score a theater review. If a review score goes down based on how many negative comments a reviewer makes, a mixed review is probably scored in around the 40 to 70 out of 100 range. So if your intent is to recommend a play, you should probably be mindful of how many critical points you bring up in your discussion of the production. I would surely recommend seeing Venables’ operatic adaption of 4.48 Psychosis to those drawn to profound, controversial human themes—loosely, what Antonin Artaud, and others, theorize theater is for. And yet, a Broadway-bound tourist, looking for a good time away from home, might really hate this show. My determination to provide critical analysis of this production, to avoid saccharine regurgitation of a sentiment of any kind, brings to mind Heiner Müller’s widely quoted comment about Bertolt Brecht that “to use Brecht without criticizing him is to betray him.” Venables deploys Kane’s disjoined sympathies beautifully in his operatic version. The haunting, melodic refrain that is repeated throughout the production does, at times, descend, bizarrely, to sound exactly like elevator music–the jarring sound effects deployed throughout the production assure there is no peace to sustain.

Photo Credit: Paula Court

The play’s “narrator” talks a lot about her prescription medication dosages. The reading off of prescriptions, and a dizzying amount of adjustments to dosages brings alive Western medicine is not working for the patient, and reads as a heartbroken plea to find the correct pharmaceutical cocktail. Nevertheless, blame is reserved only for oneself in 4.48 Psychosis. Kane’s listing of prescription dosages, it might be argued, ties back to the number countdown sequences to demonstrate, from yet another angle, the patient’s frantic attempt to return to the one number within infinity–4.48– the one time of day “when sanity visits.” A hammer banging against a pipe, a saw sawing wood, makeshift instruments in dialogue with drums, dramatize doctor-patient conversations that appear as text. Another wondrous moment from the orchestra pit: a sound much like a plane flying without an engine is concocted by a violinist. Superb freewheeling musical exchanges, alongside the superb, yet, at times, bizarrely, elevator-like music never going away, conjures up Oliver Sacks’ theory that people who suffer from neurological deficits hallucinate music.

A collage of memorable moments: the segment that begins “I dread the loss of her I never touched/love keeps me a slave in a cage of tears” seems sacrificed to the music preceding it; a segment powerfully executed, as lines of text flash upon the screen, is when the patient reveals her delusions of grandeur in a monstrous light: “I gassed the Jews, I killed the Kurds, I bombed the Arabs…” A scene where all the characters start choking each other is imprinted in memory for its dark finale. The show gets disorientating pretty often but in compelling ways. It is great to be able to watch the conductor, William Cole, and the musicians play, featured on top of the white “antiseptic” stage, versus where musicians usually play, hidden in an orchestra pit below the stage. It is a fascinating set design: the musicians as stand-ins for the soaring heights of the imagination of our deeply troubled, deep thinker, stuck down below on earth. Meanwhile, there are two small televisions, on each side of the theater, that film Cole waving his baton. The image of little TVs — with a miniature conductor trapped inside and right next to him the Exit sign glowing in big red letters–help cement the impression that the audience members are, too, beloved occupants of the asylum.

In Summary,

Humor lost to grim subject matter/couldn’t make out what the actors were singing on about/borderline elevator music/key text sacrificed to preceding music/clueless about the plot through entire segments/felt disoriented a lot, in general=Great show!

[i] Text in this article from 4.48 Psychosis is as published in Sarah Kane, Completed Plays, published by Methuen Drama, 2001.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Heather Waters.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.