A Wounded Soldier pushes pawns across a chess board while a Mother tells Svetlana the story of her child’s death at Chernobyl. Svetlana begins to weep, and wipes her eyes with a napkin. She turns the napkin into a bib covering her chest; she draws an open wound on the bib with red lipstick, rips a hole in the bib, reaches into her chest, and rips her heart out. Her heart is a red alarm clock. She offers it to the Mother. The Mother refuses it. Svetlana leaves it next to the chess set. She backs away, making gestures of small head explosions.

This image, one of many brilliantly multi-layered moments in Zinc (Zn) directed by Eimuntas Nekrosius (one of his last productions before his death on 20 November, 2018), collages monologues and images from Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel-winning documentary literature. Documentary literature is an artistic rendering of real events; documentary theatre is also an artistic rendering of real events; Zinc (Zn) is documentary theatre based on documentary literature – reality filtered through stage imagery that is layered on reality filtered through poetic license. Alexievich’s books, oral histories that she characterizes as a “piecing together [of] the history of ‘domestic,’ ‘interior’ socialism” (qtd Liu), include: War’s Unwomanly Face (1985), an oral history of women’s experiences during WW2; The Last Witness: The Book of Unchildlike Stories (1985), which chronicles the memories of children during wartime; Enchanted With Death (1993) which deals with suicide; Chernobyl Prayer (1999) which weaves accounts of people in and around Chernobyl when the reactor melted down; Second-Hand Time (2013), which “chronicles the shock and existential void that characterized the 1990s after the Soviet Union disintegrated, and helps explain the appeal of Putin’s promises to bring pride back to a wounded post-imperial nation” (Walker); and Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War (1991) which gives voice to soldiers who fought in the war in Afghanistan and their families – stories not included in the official historical narrative. For Zinky Boys, Alexievich interviewed widows, mothers, and veterans “all lost in a society that finds them of little utility” now that the war is over (Ulin). “They are reminders of a period that official culture would rather be forgotten” (Ulin). Alexievich says: “I collect the everyday life of feelings, thoughts and words […] I collect the life of my time. I’m interested in the history of the soul. The everyday life of the soul, the things that the big picture of history usually omits, or disdains” (qtd Donadio). Zinc (Zn) deals most obviously with Chernobyl Prayer and Zinky Boys, “two tragedies that accompanied the death throes of the Soviet Union, both of them simultaneously causes and symptoms of its impending collapse” (Walker). It is a polyphonic examination of the stories, characters, and situations that Alexievich has documented in her own polyphonic way: The Wounded Soldier is a character from the Afghan war, The Mother lost a child in the aftermath of Chernobyl, Svetlana is the author, and the clock refers to Second-Hand Time.

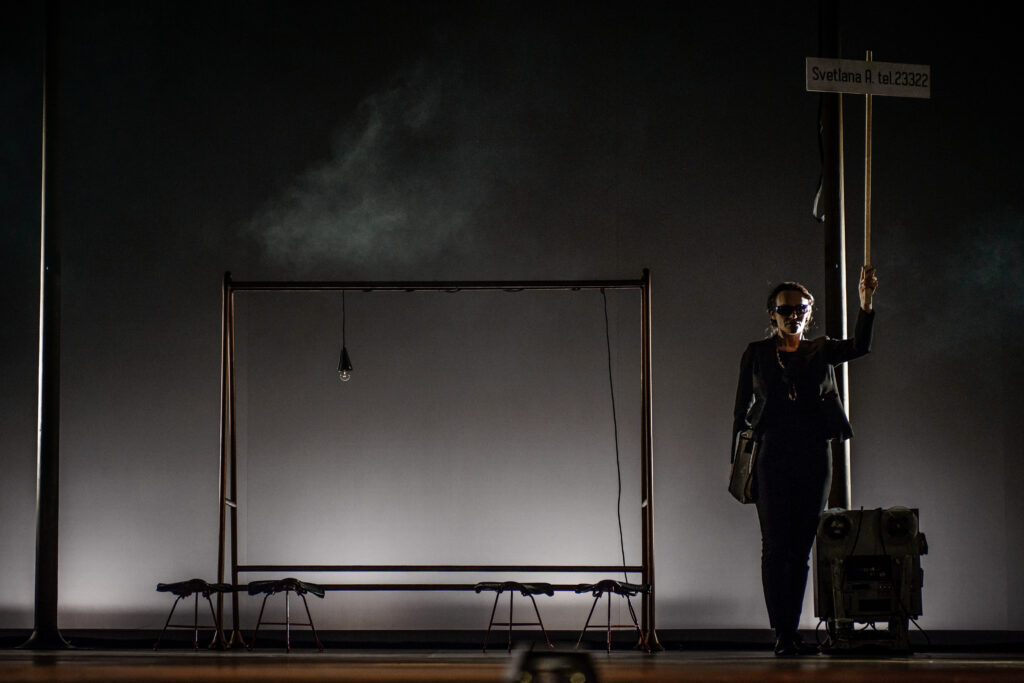

Zinc (Zn) Photo by Laura Vanseviciene

Svetlana is the central character of Zinc (Zn). She introduces herself to us as child, but for most of the play we see her as an adult, travelling back and forth through time and space dragging her reel-to-reel tape recorder behind her – sometimes to conduct interviews, sometimes because, after 2000 she was persecuted by the Lukashenko administration and had to leave Belarus, where she was born. She buys tickets to Berlin, Prague, Paris, Minsk, Tel Aviv, and tens of other cities while others in line behind her cannot get a ticket – her travel is both a privilege and a curse.

Young men – several as young as 18 – line up to qualify for the military. One proudly tells his mother he has been accepted; later a Mother says her son never returned – his body returned, but not his soul. Soon, a dead body is dumped in the center of the stage, then dragged away; then dumped again, and dragged away again; and dumped again and dragged away again. Behind the body an actress rattles a sheet of zinc to make the sounds of thunder. During the war, bodies were returned home in zinc coffins that families were not allowed to open. They were buried at night, in secret. Here they are pulled out of sight.

Medals are handed out to those who return from the war alive. One soldier says: “my name is not on the list,” but he is given a medal anyway. Everyone gets a medal – even those who clearly did not serve.

For some, Svetlana turns out to be an unreliable narrator in a world in which truth is relative. The Soviet incursion in Afghanistan was “so steeped in secrecy that until 1985 (the fighting began in December 1979), Soviet citizens were told that troops had been sent to Afghanistan to work on humanitarian and infrastructure projects, fulfilling what was euphemistically called ‘international duty’ […] Once the story of the war began to be told, the narrative became one of national embarrassment” (Ulin). Alexievich was put on trial on charges of defaming the Soviet army, and in Zinc (Zn) the trial takes the form of a soccer match: two soldiers face off over a ball of audio tape, while others, in broken and bandaged chairs, sing “Ole, Ole Ole Ole” (a common soccer cheer), and do the wave: the trial is a form of entertainment, and the soccer game is a nationalistic rally. One by one, soccer fans come forward to accuse Svetlana of changing people’s perceptions of the war: one Mother says she is not the mother of an assassin, that Svetlana has ruined her son’s good name, and that he fought in Afghanistan because he was an honest man. Another Mother accuses Svetlana of using her son to become famous, and makes a noose out of a fire hose, challenging Svetlana to hang herself. The noose refers to Enchanted With Death, while the fire hose refers to the fact that fire-fighters at Chernobyl sprayed their hoses at a radioactive fire in their shirtsleeves while townspeople gathered to watch. Lights change after the trial in such a way that we are not sure if it happened “in real life” (whatever that has come to be) or whether it was one of Svetlana’s nightmares (if so, her nightmares are tamer than any nuclear disaster Alexievich has covered). Svetlana repeats the gestures and sounds of her head exploding.

Zinc (Zn) Photo by Laura Vanseviciene

Zinc (Zn) does have a few light moments: as Svetlana drags her huge reel-to-reel tape recorder behind her, she stops for a cigarette. Her lighter isn’t functioning, but a handsome man literally parachutes onto the stage to light her cigarette for her. Her phone rings, and she reaches into her satchel to answer it, pulling out a large red rotary phone. “Hello? Hello? Hello?” No one answers. An electrician enters with a tangle of cords to tell her the phone is not connected to anything. Hilarious – and not.

Ultimately, however, we feel the loss, betrayal, and confusion of the characters whose stories we hear. Their bewilderment is dramatized by a moment near the end of the first act, in which a guard tells the audience to leave (and house lights come up) – but then, as one audience member takes the guard at his word and starts to move toward the exit, the guard yells “Sit Down!” and the play continues.

Act 1 and Act 2 end with a mournful rendition of “Happy Birthday” – a requiem to those whose birthdays will never be celebrated again.

Nekrosius links the competition of soccer and chess to the kind of competition that leads to a nuclear arms race, and to war. The production itself, like the books, “traces the emotional history of the Soviet and post-Soviet individual through carefully constructed collages of interviews” and, in the case of this production, images. Both the books and the production give voice to those marginalized by official historical narratives. Additionaly, the production’s collage-based dramaturgical structure demands the kind of critical thinking that could prevent these catastrophes from occurring.

Zinc (Zn) was the opening production of the Napoli Teatro Festival.

Zinc (Zn)

Produced by Meno Fortas Theatre and State Youth Theatre

With a support of Lithuanian Culture Council

Directed by Eimuntas Nekrošius

Scenery by Marius Nekrošius

Costumes by Nadežda Gultiajeva

Composer Algirdas Martinaitis

Lights Audrius Jankauskas

Cast

Aldona Bendoriūtė, Simonas Dovidauskas, Sergejus Ivanovas, Adomas Juška, Ieva Kaniušaitė, Dalia Morozovaitė, Milda Noreikaitė, Aušra Pukelytė, Vygantas Vadeiša, Vaidas Vilius, Genadij Virkovskij

References:

Donadio, Rachel. 2016. “Svetlana Alexievich, Nobel Laureate of Russian Misery, Has an English-Language Milestone.” The New York Times. 20 May. Accessed 10 June, 2019.

Liu, Max. 2016 “Book Review: Second-Hand Time.” The Independent. 25 May. Accessed 10 June, 2019.

Ulin, David L. 2015. “Svetlana Alexievich’s Zinky Boys Gives Voice to the Voiceless.” Los Angeles Times, 3 December. Accessed 10 June, 2019.

Walker, Shaun. 2017. “Svetlana Alexievich: ‘After communism we thought everything would be fine. But people don’t understand freedom’” The Guardian, 21 July. Accessed 10 June, 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Erin B. Mee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.