One of the highlights of Lluís Pasqual’s years at the helm of Madrid’s Centro Dramático Nacional (Spanish National Theatre between 1983 and 1989) was a production of Federico García Lorca’s little known Comedia Sin Título (in English Play Without A Title) in 1989. Pasqual’s lithe staging of Lorca’s incomplete play saw revolution break out in a theatre where A Midsummer Night’s Dream—Lorca’s favorite Shakespeare play—is being staged. The skeletal plot brings together the production’s director—known as the Author—with the cast rehearsing the play, backstage staff, and audience members who comment on the ensuing action. Pasqual’s production was angry, eloquent and poetic: a debate about the function of theatre in troubled times with Imanol Arias as a lean, angular Author, tormented by angst, melancholy, and despair. Now Pasqual returns to this 1936 play, only Alberto Conejero has provided two new acts–a jazz riff on the first act that doesn’t pretend to complete the play but rather offers a dialogue with the motifs of the original work. The result is El Sueño de la Vida (English title The Dream Of Life) premiered at Madrid’s Español theatre on 17 January–a play where the theatre is the battleground over which dreams of both the role of theatre and its place in forging a more egalitarian society is debated.

The staging opens at fever pitch as Nacho Sánchez’s angry, impatient Lorenzo–known as the Author but as much a director as an author–rants against a theatre he wants to change. Lorca’s text has been expanded into a diatribe against a theatre that seeks to sanitize and amuse with no other purpose. He wants a theatre without limits: where one can flood the stalls with stars, the walls can be torn down and strong lights burn those inside. His cries are as much a cry for help as a lament: he berates the spectators, he screeches in despair. He moves and speaks with a jittery intensity. He moves from his stage management desk, in the middle of the stalls, to the front of the stage where, dressed in black jeans and sweatshirt, he calls for a theatre of truth. He paces in desperation like a caged animal. He advocates for a theatre of real flesh and blood men and women where the action feels immediate and necessary, where audiences go not to see what happens to others but what is happening to them. It’s an important distinction and one which lies at the heart of Pasqual’s vision of theatre. When Lorenzo asks how to take the smell of the sea to the theatre, there is a something of a suggestion this is a question Pasqual has been grappling with his entire career.

Lorenzo appears perpetually on edge. He calls for a coffee, bought in on a tray by a waiter (Raúl Jiménez) who looks as if he has been conjured from another era. In a pristine white apron, with a droopy Mexican mustache and curt, crisp answers to all questions, he is a veritable contrast to the flapping, floundering Lorenzo. The Young Man (Daniel Jumillas)–many of the characters both in Lorca’s original and Conejero’s expanded version are given roles rather than names–who appears to be Lorenzo’s lover, sits in a box up in the circle, watching the action dressed in pristine white. He is cool and composed, offering a veritable contrast to Lorenzo’s hot-headed passion. He appears to float as he walks, almost ephemeral in his presence. His 1930s white suit evokes the Lorca that remains frozen in black and white images.

An element of surprise is never far from the stage. A male spectator interrupts the action–one of two couples “planted” in the audience by Lorca to root the action firmly in the auditorium. César Sánchez is excellent as the irate middle-aged spectator who is not prepared to engage with Lorenzo’s vision; he makes the case for his own judgment as a spectator as overriding the “intentions” or wishes of the author. Ester Bellver plays his wife. Embarrassed by the ruckus her husband generates, she tries to placate him before an audience who look around to them to see what the commotion is all about. The male spectator leaves the auditorium in anger, lamenting that he hadn’t gone to the Latina theatre—a venue not far from the Español specializing in commercial theatre—pursued by his wife. The reference to the Latina is one of a number of contemporary additions made by Pasqual and Conejero to Lorca’s Act 1 text.

The second pair of spectators “planted” in the auditorium are somewhat more unsettling. Enrique (Sergio Otegui) may appear more reasonable than the fuming first male audience member but he is altogether more menacing, a man who is beating his wife Guillermina (María Isasi)—he murders her before the play’s end. He appears to represent civility and manners but scratch below the surface and an altogether more dangerous character emerges. He uses bullying as a way of keeping what he sees as order, shooting the worker who enters the theatre with news of the revolution. He evokes a god of vengeance who acts for him as a personal henchman. I saw the production on the eve of a protest organized by right-wing extremists on February 10. 45,000 right-wing sympathizers gathered to outside the Parliament building in the center of Madrid—many brandishing pre-Constitutional flag—to protest against Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s supposedly conciliatory position on Catalan separatism. Enrique’s lines seemed to echo the language I heard on the news that evening from protestors unable to recognize the need for discussion and negotiation.

The action moves from the auditorium to the stage, as backstage palaver points to activities behind the scenes. Performers peep from the partially opened curtains. Juan Matute’s Fairy and Koldo Olabarri’s Sylph with their gold leaf hats and blue and rose gold outfits look to have stepped out of rehearsals for a Lyndsey Kemp mime. Their white faces, party dresses, and outdoor boots merge the feminine and the masculine and echo something of the complicity between the Figure in Vine Leaves and the Figure in Bells from The Public. Chema de Miguel’s Prompter, glasses perched on his nose and script in hand, dressed in neat matching trousers and waistcoat is always trying to do the right thing. Juan Paños’s Woodcutter with an aqua blue painted nose just wants the show to go on while and Dafnis Balduz’s Nick Bottom—in red holding an ass’s head—may appear part of the group at the opening, but looks curiously marginalized from the action as the piece progresses. Rehearsals for A Midsummer Night’s Dream appear to have been halted. Emma Vilarasau’s Actress, playing the role of Titania, appears to be in an on/off relationship with Lorenzo. She marches through the center aisle and appears in red shoes and a striped black and rose gold dress that evokes Cleopatra. She seeks to embrace Lorenzo but he pulls away.

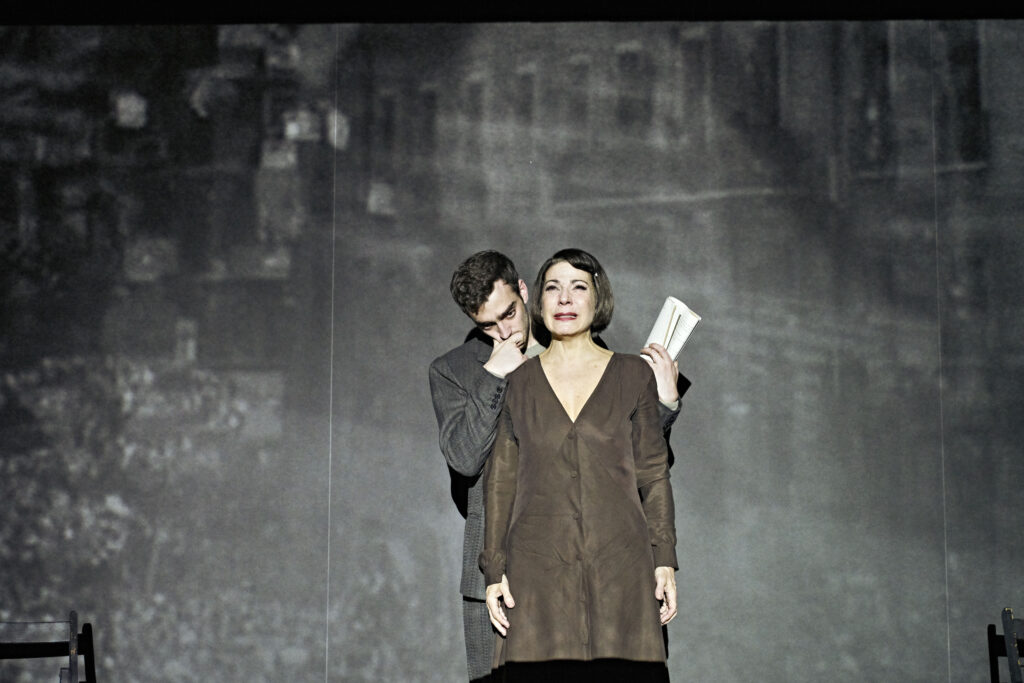

Nacho Sánchez and Emma Vilarasau in The Dream Of Life. Photo: Sergio Parra.

The curtain rises on an empty stage where the Fairy and Sylph cling together from the depths of a trap door. Emma Vilarasau’s Actress appears to be on her way out, coat on. The owner of the theatre (Antonio Medina) is in the auditorium, concerned at the commotion. The sound of bombing has generated an alarm. The action is fast moving and chaotic, with distinct pockets of activity across the stage and auditorium. The second set of spectators are now on stage; Guillermina is concerned for her children–a stagehand (Jaume Madaula) runs off to help find them. The Actress moves to tutor the desperate mother in how to make her wailing cries credible, one of many references to performative efficacy; the Stagehand sets fire to a poster for The Dream Of Life. The end of Act 1 ends with panic, the escalating sound of a frantic piano riff suggesting a world veering out of control.

Act 2 moves back to the 1930s. The curtain rises on a rehearsal room with an assortment of chairs, a moveable staircase, and table. A pianist (Miguel Huertas) sits at a piano stage right; he underscores much of the dialogue that follows. A percussive rhythm is set by an actor (Iván Mellén) who deploys a box as a makeshift drum kit, adding further urgency to the accompanying baseline. Act 1 is replayed here, in a parallel universe where the characters present variations on the action seen, narrated or alluded to earlier. Lorenzo is now dressed in a suit directing a rehearsal from the front of the stage. A costume palette of beige, mustard, brown and bluish grey suggests something of a sepia photograph. The Woodcutter keeps repeating that he’s Shakespeare’s moon. Bottom wears a golden ass’s head. The Stagehand’s mother (Ester Bellver)—with something of the protective matriarch of Blood Wedding—is also present. The action stops and starts; the language feels curiously familiar.

Remnants from interviews given by Lorca as well as his earlier works, including Poet In New York, and The Love Of Don Perlimplín, and Belisa In The Garden, are juxtaposed by Conejero with newly crafted dialogue. The Young Man wanders through the action, a ghostly other still in white–the only character to remain in the same attire as in Act 1. Lorenzo is both present and absent. He falls repeatedly to the floor as if dead, the Young Man and the Actress mourn his lifeless corpse and then he rises again to continue to work on the production and to watch the Young Man and Actress who make claims on him. It is as if he is both inside and outside the action, participating and observing. His recurring demise also suggests history repeating itself. The owner of the theatre may claim that theatre people shouldn’t get involved in politics and the Woodcutter just wants to be left to play his role, but politics is shown to be at the heart of the action. Lorenzo, who believes that theatre and revolution should be the same thing, has opened the doors of the theatre to students. The Stagehand puts a gun to the owner’s head. A student uses the staircase as a soapbox, calling for a theatre for the future of a new Spain. The pianist plays The Internationale. The bullying audience member berates his wife for having brought him to the theatre. The Waiter, now dressed in a blue shirt that associates him with the right-wing nationalist falange movement has returned with news that the revolution has been quashed; he speaks of loathing the theatre and all who work in it, killing the student in cold blood. A screen falls down at the back of the stage, projecting grainy black and white images of the Spanish Civil War–a way of signaling the devastation that follows. The Actress removes her wig and her brown dress, naked in front of the screen she calls for a theatre filled with fire, for a cataclysm to save them from the horrors now present. The configuration of lines from some of Lorca’s most angry poems from the Poet In New York anthology–Ode To Walt Whitman, Cry To Rome, Christmas On The Hudson point to this as a scream. And it on this note that Act 2 ends.

Act 3 is a brief epilogue to the action: the calm after the storm. It pits Lorenzo (now once more in the contemporary clothes worn in Act 1) and the Young Man in a dialogue. The curtain rises on 12 bodies laid out in a row, the casualties of the horrors narrated by the Actress. It evokes both the final scene of The Public as the Director and Magician do verbal combat over differing visions of theatre and a lament for Lorenzo who may have perished in the revolution, his body, like Lorca’s, never found.

Alejandro Andújar’s set deploys the width of the Español theatre to good effect. The curtains that drive the action to the front of the auditorium in Acts 1 and 3 are lifted in Act 2 as the audience are taken into the depths of the theatre—chairs moved to form a semi-circle, a row, a makeshift barricade. Nacho Sánchez, who had taken the role of the young soldier who imprisons Lorca’s former love Rafael Rodríguez Rapún in Conejero’s La Piedra Oscura (English title The Dark Stone) in 2015, is a lean, brooding Lorenzo with echoes of Hamlet. The relationship with Vilarasau’s Actress – the Gertrude to his Hamlet—is one that negotiates a delicate line between dependency and resentment. Vilarasau, with more than a nod to Nuria Espert in her inflection, gives a performance where vulnerability melds with ferocity. There is poise, guile but also desperation: as she removes her wig in frustration, as she repeatedly clutches at Lorenzo, as she looks for a sense of purpose in a rehearsal that has spiraled out of control. Pasqual’s agile production allows the configuration that Conejero conjures with Lorca’s play to remain fluid. The choreography is busy and mercurial. Act 2 may be a dream with Lorenzo both participating in and watching his own life from a distance, but it may also be a rehearsal where the fourth wall tumbles, as in Six Characters In Search Of An Author. In the end, we are left with both defiance and passion: the belief that theatre matters as a site of intervention and possibilities. The Dream Of Life closes with the sound projection of Lorca’s supposed voice articulating Lorenzo’s opening lines from Act 1. There is no known recording of his voice but actor Juan Echanove imagines, just as Conejero does with the play, what might have been, offering a reflective engagement on the politics, performance, self and other that remains all too timely in these troubled times.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.