American playwright, translator, and journalist Amelia Parenteau is currently in residence in Paris, France, where she has been writing about the contemporary theatre scene in that city for TheTheatreTimes.com. In her third article, she examines the question, “Where are the women in French theater, and what’s being done about their under-representation?”

When I left New York last spring, the most recurrent debates I heard fell under the umbrella of insufficient representation of diversity, in terms of race, gender, age, ability, and experience. Here in Paris, with its own version of the Occidental, patriarchal culture of theater, I’ve witnessed the same under-representation of diversity, but outraged discourse does not dominate the conversation. I’ve come across a murmur, though, that is quickly rumbling into shouts: feminists are standing up for the representation of women in theater. And it’s about time.

According to a survey conducted by the Société des Auteurs et Compositeurs Dramatiques (SACD) (Society of Dramatic Authors and Composers), in the 2014-2015 season in France, 35% of all choreographers, 28% of directors, 24% of playwrights, 21% of instrumental soloists, 5% of librettists, 4% of orchestra conductors, and 1% of composers were women. These statistics expose the bleak reality of the representation and recognition of women in the dramatic arts in France, and make the need for the law mandating parity, passed August 4, 2014, all the more apparent.

Najat Vallaud-Belkacem

This law is representative of the attempt at enforced parity instated by President François Hollande. Although he was not the first French President to promise male-female equality in his government (Sarkozy made the same declaration while campaigning in 2007), he was the first to achieve it. In Hollande’s 34 member cabinet, 17 of his ministers are women. Notably, he has engaged Najat Vallaud-Belkacem as the Minister of Women’s Rights. Vallaud-Belkacem was charged with creating a law requiring equal opportunity and remuneration for women in the workplace. Article 1 of this law (“for true equality between men and women”) states, “The policy for equality is comprised notably of actions intended to guarantee equal treatment of men and women, and equal access to cultural and artistic creation and production, as well as the diffusion of their work.”

Legislatively, the French have clung to antiquated systems and codes of governance that are exclusive of women (if not overtly, due to lack of opportunity in education, hiring, and lack of recognition for the women’s work). Hiding behind claims of idealism, they are reluctant to change the language of the law in order to require parity, claiming that it will diminish women’s perceived value to have them filling positions of power by mandate, rather than by merit. Instead, they would like to see the (entrenched, patriarchal) systems change themselves so that women will have better chances of being considered for these positions of power. This debate over the idea of changing the constitution to require equal representation of men and women in government by enacting quotas came to a head in 1998, although little real change ensued, which makes Hollande’s purposefully balanced cabinet a striking gesture, in the sphere of French politics.

With the law in place and more women in positions of political power, it would appear the time is ripe for change. And indeed, the members of HF Ile-de-France are done waiting. They have mobilized to create concrete demands for which they can hold themselves, and their partner theaters, accountable. French feminists, male and female, are lining up to show their support. Last year (2013-2014) was the first “Saison Egalité” (“Equality Season”) in France, organized by HF Ile-de-France, an organization dedicated to fighting for the equal representation of men and women in arts and culture. I attended this season’s opening night at the Théâtre de Montreuil, one of 29 participating theaters this year. These theaters committed to fighting artistic and cultural discrimination against women by creating seasons with a balanced programming of pieces created by men and women, an equal distribution of their budget to men and women, a balanced structural reorganization, and ample publicity of their commitment to equality. The HF Ile-de-France equality project has asked theaters to make these commitments for three consecutive seasons (at least!) and to use the strength of their partnership to learn strategies in building equality from one another.

Photo: Ariane Mestre

The evening of the opening night consisted of a series of conversations about the importance of equality, interspersed with trivia about female theater artists throughout French history, and short performances. Some important statistics were cited, such as the fact that women earn, on average, 28% less than men, that there are only 2 women interred in the Pantheon, alongside 71 men, and that there are more women in positions of power in the French army than in French theater. More abstract topics were also discussed, such as the importance of language in affirming women’s roles in society, a particularly potent question, considering that French is a language with gendered nouns. (I recently learned that the feminine version of the word “author” (“autrice” instead of the masculine “auteur”) was suppressed by the Académie Française in the 18th century, because the profession of author was not considered suitable for women, as it would accord them too much influence and power.)

Marie-José Malis

The speakers acknowledged that French history and culture are much more patriarchal than neighboring countries’, giving the advancement of the Nordic countries as an example. They also acknowledged the fact that true parity in the arts is nigh impossible because every artist is an individual and quotas are a touchy subject. My favorite speech was delivered by Marie-José Malis, a director and the Artistic Director of La Commune, CDN d’Aubervilliers, a theater in the Parisian suburbs. When asked about how she legitimises her position as Artistic Director to those who question her power, she replies that women in theater work to change and redefine the very jobs they hold, the rules they enforce, and the goals they envision. Because women have not traditionally held these positions does not mean that they are unable to continue the traditional success of a theater, it means that once they are in power, they are going to help the entire theater community make significant cultural changes in the way women are treated and acknowledged in the theatre. Malis said, “Parity invites women to employ their capacity to think of new means of doing things. Women are the avant-garde, and they are involved in theater to offer their different perspective, as all artists should do.” For this declaration, Malis practically got a standing ovation.

All the speakers agreed that in order to make lasting change in the accepted practices of the arts and culture, a two-pronged approach is necessary: training girls from a young age that their work is just as valuable as their male counterparts’ (and vice versa), and creating rules of parity within existing systems in order to provoke institutional change. There was unanimous agreement that “we” need to stop thinking that artistic directors have the right to be totally free in their season programming if we are expecting to see any change.

Thankfully, the HF Ile-de-France group is not acting alone. I attended a conference on “Femmes Artistes, Femmes Engagées” (“Women Artists, Engaged Women”) in October that was part of the Ile-de-France Festival, a celebration of music and cultural heritage that takes place every autumn in Paris and its surroundings. The conference took place at Sciences Po, a prestigious and demanding school for the study of international relations in Paris, and the panel was comprised of two feminist scholars, one journalist, and two female musicians. The conversation was long and lively, and touched upon many of the same questions that were broached in terms of theater: women need more opportunities, more encouragement in their education to pursue their musical passion, and more recognition and positions of power once they have made a name for themselves.

They also cited statistics and anecdotes reflecting women’s under-representation in the music industry, saying that only one-quarter of all musicians are women. There was much discussion of the particular challenge posed to women in performing their music because their performance is so linked to their physical appearance. The consensus seemed to be that women can find power in desexualization, by denying that their body imposes limits to their creative productivity; and yet, there is an equal empowerment to be had in embracing one’s sexuality and proudly incorporating it into one’s performance. It should be up to every artist to decide how she wants her relationship to her body to figure into her musical performance.

Geneviève Fraisse, a renowned feminist scholar in France, commented that France is currently in a period of trying to redefine its history and its relationship with its present cultural identity. Women not only need to participate in this conversation but also to look at the way that their own story is told. At present, the story of women throughout history is one of suffering: being objectified, subjugated, and denied opportunities to pursue their interests, or denied credit for their accomplishments. Instead, Fraisse suggests, women need to change the way they tell their own cultural story. Yes, this tale of suffering is equally a story of exclusion, but look at how female artists benefitted from this exclusion, citing Virginia Woolf as her prime example. Fraisse encouraged women, particularly women artists, to take advantage of this opportunity, in this time of shifting cultural identity, to create and offer another model of organizing our social and cultural systems.

Perhaps no group in France is doing a better job of profiting from their exclusion than La Barbe, an activist group that has made a habit out of invading places traditionally dominated by men, sporting beards of their own. (“La Barbe” means not only “The Beard” in French, but is also used colloquially to refer to something that is a pain in the neck.) Their stated mission is to “denounce the hegemony and the monopoly of power, prestige, money, and privilege that thousands of white men have clung to through their codes, habits, values, and philosophy.” These women have imposed themselves upon restaurants, conference rooms, business and union meetings, and prize juries, in order to expose the prevalence of men in positions of power in all sectors of professional, political, cultural and social life. Their protests usually involve their unannounced interruption of an event, their insertion of themselves at the heart of it, the reading of a tract, and then their eventual ejection by security guards.

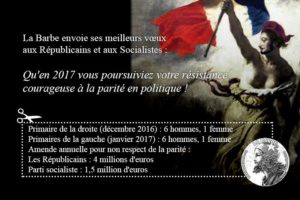

One of La Barbe’s tracts, condemning underrepresentation in the last presidential primaries (from Les républicains and the Socialist parties).

In October, I participated in a protest staged by La Barbe on the steps of the Odéon Theater, one of France’s five national (i.e. completely government-funded) theaters, directed by Luc Bondy. (Of the five national theaters, La Colline is the only one to participate in the HF Ile-de-France “Equality Season.”) We took to the steps of the theater on the opening night of the season, while patrons flocked in to see Robert Wilson’s production of “Les Nègres” by Jean Genet. Despite vague promises for more balanced male/female programming this season, there is only one female director/playwright scheduled at the Odéon this year, as compared to seventeen male director and playwrights.

We sported beards and there was even one woman dressed as a witch, we held banners and signs, and we passed out flyers and brochures with SACD’s statistics. As the flow of patrons into the theater thickened, one woman started reading the statistics over a megaphone, followed with a refrain of “Where are the women?” to which we would respond, “Nowhere!” Amongst the various celebrities who were present for the opening, (American) Laurie Anderson was the only one to approach us and express her solidarity. Luc Bondy, on the other hand, turned his back to us and ushered his patrons into the theater, assuring them that we were “crazy.” One outspoken patron suggested to us that if we women wanted more representation in the theater, we should try harder to make ourselves and our work known. His girlfriend quickly whisked him away before things could escalate.

As a friend of mine pointed out, the SACD’s statistics and La Barbe’s protest do not take into account the number of female actors who are working each season. This disparity stems from the historical cultural values placed on actors/actresses versus authors. Like in English, “actrice” (“actress”) is an accepted word where “autrice” or “authoress” is much less common. Traditionally, whereas (male) authors were lauded for their work, wielding their voice as an instrument of intellect and power, (female) actresses were considered to be near-prostitutes, selling their bodies for a living. Therefore, although actors and actresses (and all the backstage crew) are indispensable to the creation of a successful piece of theater, the protests are targeting those positions of power within the structure of theater that have typically been dominated by men as those that need to change.

Muriel Mayette-Holtz

The last time I was in Paris, I had the opportunity to interview Muriel Mayette-Holt, Artistic Director of the Comédie Française, France’s oldest and most prestigious national theater. Named to the position in 2006, Mayette-Holtz was the first woman to direct the theater since its founding in 1680, but has since been replaced by Eric Ruf. When I asked her about her unique position, she was extremely diplomatic, saying that she was not trying to claim anything by occupying the role, nor transmit any political message. Instead, she was directing the theater as an expression of her love for the institution which she had devoted herself to since she was 14. She acknowledged that her selection as the director was highly contested, and that she would like to see more women in all the realms of theater, but she considered her work to be to do all that she could to direct the theater to the best of her abilities. She told me, “I make theater for everyone, men and women. I don’t see it as a question of sexuality, but as a question of humanity.”

Thankfully, change is in the works, slowly but surely. Hollande’s shining example of parity within his cabinet has caused a ripple of changes in French theater administration, causing women to finally receive the upgrades in title and recognition that they deserve. Whereas many women have spent their careers working as “assistants” to their male counterpart artistic directors, they are now being recognized with the title “co-director” for the work that they do in scouting new talent and effectively programming the season by determining what they pass along to the artistic director. Activist groups like HF Ile-de-France, La Barbe, and SACD are asking all the right questions and demanding better answers. Where are the women? Everywhere, in fact.

Amelia Parenteau is an American playwright, journalist, translator, and cultural commentator currently living in Paris. She is a graduate of Sarah Lawrence College where she studied writing, theater, French, and gender studies. She has worked with TCG, Ping Chong & Company, and the Lark Play Development Center in New York, and the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut. She is a member of the FENCE and the League of Professional Theatre Women, and she has been published in Asymptote Literary Magazine and American Theatre Magazine.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Amelia Parenteau.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.