Of all of the performances and plays I have seen, this one stands out uniquely for several reasons. It is a collectively devised piece by three women of color who choose not only to create in this manner but to also integrate collectivity into the plot of the piece itself. The decision-making Council of Mothers is such a structure. Secondly, Where Earth Meets the Sky presents a post-apocalyptic vision of the Earth as a newly invented place of peace and development, rather than the usual barren, violent and dystopic world that Hollywood regularly dishes out in their high-tech, blockbuster but thinly plotted films. Thirdly, this piece creates a corporeal, gestural language that enables a respectful and ritualistic style of communication between the characters that is also quite legible to the audience. And lastly, this piece openly and directly addresses the issues of historical colonialism and its painful impact on the body of women.

Further, it dismantles capitalism and neoliberal economics while simultaneously devising a post-apocalyptic world that places environmental issues up front and center in an integrative way without resorting to preachiness. While the play’s premise is straightforward – what happens when the star people run out of food and return to Earth? – the moral and ethical issues are complicated, and the mise en scene subtle. Going beyond the labels, Where Earth Meets the Sky is a well-thought-out, deeply political play that is firmly grounded in Afro and Indigenous futurism (according to the playwrights), and I would also add Latinx futurism (the x indicates the non-binary gender identities and the script calls for such casting).

The Plot: Forty generations or about 1,000 years ago as of 2050, the Earth became decimated by human greed. Those with corporate privileges were taken on OmniVessel into outer space, leaving behind what they thought was a planet soon to be devoid of all life. The human inhabitants of OmniVessel, the White Hairs, have been indoctrinated into believing that Earthroot brown peoples were savages and deserved to disappear. The year is now 2.040 and the White Hairs are on a mission of survival to (re)conquer the Earth at whatever cost due to the pending failure of their food generators.

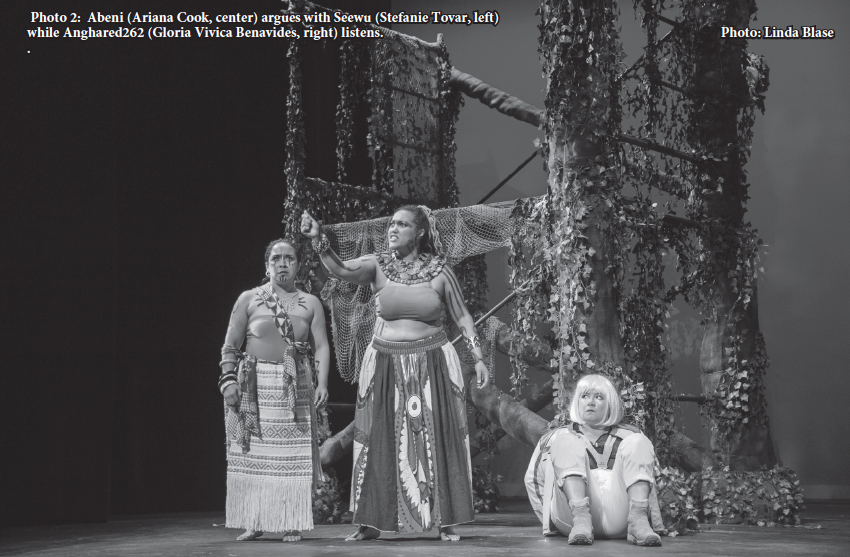

Things get complicated when OmniVessel lands a probe on Earth, commandeered by the white hair scout whose orders as a Military-One officer are the “seizure of samples and the re-occupation of Earth” at whatever cost. The conflict centers upon the triangulation of three characters: the white hair intruder Anghared262, the Earthroot Seewu who turns out to share ancient blood ties with Anghared262, and Seewu’s Earthroot spiritual twin Albeni, a woman whose memory of the near extermination of Earthroot people is firmly anchored within.

Things get complicated when OmniVessel lands a probe on Earth, commandeered by the white hair scout whose orders as a Military-One officer are the “seizure of samples and the re-occupation of Earth” at whatever cost. The conflict centers upon the triangulation of three characters: the white hair intruder Anghared262, the Earthroot Seewu who turns out to share ancient blood ties with Anghared262, and Seewu’s Earthroot spiritual twin Albeni, a woman whose memory of the near extermination of Earthroot people is firmly anchored within.

Unbeknownst to the White Hairs, who expect to land on an unpopulated Earth, the brown Earthroot people actually survived and even thrived on Earth. However, there is a new world order. Long gone are the days of patriarchal rule, of capitalism, and neoliberal economic policies. Long gone are the days of rule by a single, male commander-in-chief. The new world order now belongs to women of color and to their Council of Mothers. Decisions are made communally in accordance with a shared set of values, such as venerating their ancestors, protecting the Earth and each other, and what they call Earthroot tree-based technology and blood memories. These memories are gifted to individuals, who share them with the community and serve as guidance. One such memory is gifted to the invader Anghared262 when she remembers (has visions of?) the now prehistoric protests and chaos of the last days on Earth a thousand years ago. Anghared262 develops an Earthroot tattoo on her skin, which all Earthroot people have), which indicates ancestral ties with Seewu. This complicates matters since Anghared262 can no longer be seen as a pure white hair star person by Earthroot people, thus splitting the community as to how to deal with the pending invasion.

Simultaneously, Seewu is also gifted a prophecy about the return of the former brown skins to Earth and believes in a peaceful discussion with the invaders. On the other hand, Albeni (Seewu’s spiritual twin) strongly contends that the White Hair star people, even if they do have Earthroot ancestry, have not been Earthroot for a millennium and do not know their ways. Judging from Anghared262’s aggressive behavior upon landing, Albeni contends that they have not changed, thus if allowed to land, history will repeat itself through their greed and destructive ways. She is in favor of pre-emptive military action against OmniVessel before they land any more probes on Earth.

Earthroot peoples have lived in the relative seclusion of a peaceful Earth ruled by collective enclaves and where there has been little opportunity for the type of dissent they are now facing. For the first time in a millennium, they confront internal fragmentation. The Council of Mothers has always shunned the use of violence; however, now their pacifism may lead to their demise.

The scenario clearly alludes to the age-old ethical dilemma faced by strict pacifists (like Mahatma Gandhi) who reject violence at all costs reiterating that the means are as important as the end. Violating one’s principles will never bring the desired end. On the other hand, one of the Just War arguments is that war is allowed only if survival is at stake. The brutal conquest and colonization of native peoples in the Americas and the enslavement of African descent peoples served as a clear reference within the performance, particularly how this brutality affected the violated bodies of women, their sexuality and reproductive rights.

In the spirit of following the creators’ collective footsteps, my article engages in direct conversation with the playwrights by way of numerous email and personal exchanges. When I suggested the issue of trust as an underlying dilemma, Edyka Chilomé responded with a broader perspective:

Chilomé: I think the theme of trust is explored on so many levels in this work: Do we trust each other, do we trust ourselves, do we trust the relational power of a larger design outside of what we can understand? These questions seem timeless in our explorations as human beings. As writers, and more significantly as daughters of the persecuted and silenced, it has been a question of do we trust the potency and healing power of our stories. Do we as humans trust that our gifts and our passions hold answers for our people, for our world, for ourselves? This story reflects the questions that arise in the constant “drama conflict” in our lives, questions that we must learn to hold as a constant pulse in our learning and in our healing

In the Study Guide developed for the Cara Mia Theatre website, Chilomé elaborates on the issue of historical traumas:

Chilomé: Engaging topics such as historical traumas and present day violence against communities of color and women has been a personal collective process of unraveling. It has caused the cast to engage in powerful and introspective conversations around personal identity and political perspectives. These conversations have inspired creative expression that has certainly translated on stage. Moreover, the process of writing and producing this story was very much a creative effort to break conventional forms of hierarchy in the dominant culture of theatre. The challenge of such a task has resulted in re-imagining the work it takes to truly change violent paradigms in western story telling.

So, I asked about where the idea for this piece came from. Vanessa Mercado Taylor is credited by the two co-writers as the originator both of the idea and the collectively devised process.

Taylor: The seed for me was planted when I was working with Pangea World Theatre in Minneapolis. I was for the first ime in a space where my identity as a brown woman was honored and where the unique traditions of my family and my gente were included. It was revolutionary for me…I realized how much white privilege and interalized racism I had been carrying and the connections to my parents’ own trauma as immigrant…I’ve always felt a need to work collectively rather than invdividually, so I reach outed to David Lozano at Cara Mia and offered the idea of bringing together the women of the CM ensemble to explore further. For me, a lot of the questions kept taking me to my Indigenous root. I felt a deep need to learn about myself in relationship to the land and to ways of my ancestors. And collectively, we started seeing a common thread in our explorations, we kept coming back to questions of colonization, race, gender and of healing for the future. The idea of reaching across time for hope and healing, Sci-Fi just made sense…together we were intentional about decolonizing our work and ourselves. Once we committed to telling the story through Indigenous Futurism, we began to understand the importance of this choice and its reflections in the world…Indigenous Futurism and Afrofuturism are essential to our communities as we reclaim the ways of our ancestors while asking important questions about ourselves and our world.

How long did the process take?

Taylor: Four years from idea to world premier.

Following up with why a futuristic Sci-Fi piece, Mercado Taylor here agrees with her co-writers:

Cook: I loved the idea of Sci-Fi because it was co-opting a genre that has been dominated in mainstream media as a perfect illustration of white supremacy, colonialism, patriarchy, and anti-envrionmentalism. We were able to take an entry point from which many people like to consume and flip it to re-imagine what an equitable world would look like. One that doesn’t continue to ignore our existence, but acknowledges our bodies, lives, and contributions to this world.

Chilomé: Imaging our future as colognized people is an act of resistance. When we live within a dominating system that is designed to perpetuate or cultural, spiritual, and physical erause and death, daring to imagine our resilence and survival is radical. It is a gift of hope to our people and it is reclaiming of our narrative.

But this is not simple neo-nativism. These post-apocalyptic Earthroot people have developed a sophisticated system of biotechnology that operates directly from their bodies and communicates with the bodies of all sentient beings around them, including plants. No need for fancy bling bling gadgets in the scenic design which (re)creates a verdant Earth.

The following dialogue demonstrates both the aggressive nature of Anghared262, the sophisticated Earthroot technology and the language they use:

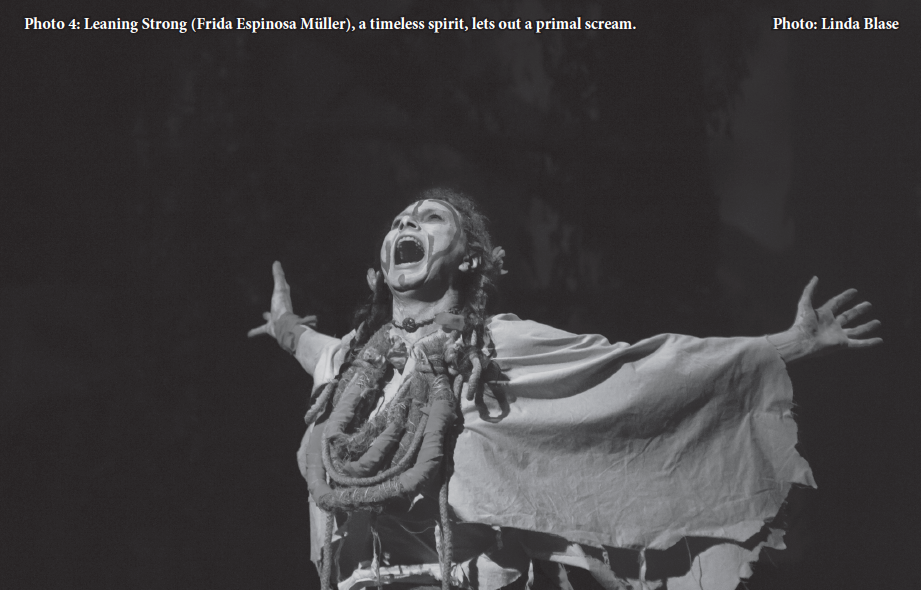

[Anghared262] hears the sounds of footsteps approaching. LEANING STRONG enters and immediately spots her. ANGHARED262 steps out with her gun pointed, her other hand up in the “step” position.

ANGHARED262: Stop! Get Down!

LEANING STRONG does not respond.

ANGHARED262: Get Down! I will shoot. Come no closer!

RUNNING MOON enters.

ANGHARED262 points the gun at RUNNING MOON.

ANGHARED262: You! Come no closer! I will shoot!

ABENI enters from behind ANGHARED262.

RUNNING MOON: (Shouting to ABENI) Aguaora- watzama! (“Watch Out!”)

ANGHARED262 is startled. She turns around and points the gun at ABENI and shoots. Nothing happens. RUNNING MOON launches at ANGHARED262 and disarms her. A struggle ensues. It is obvious that RUNNING MOON is not fighting with all their strength. ANGHARED262 pins down RUNNING MOON. There is a moment between them. ABENI seizes this chance and takes down ANGHARED262 but RUNNING MOON stops them.

RUNNING MOON: Kaa! Es Mochik! (No! Stop!)

ANGHARED262 takes this opportunity and kicks Abeni hard in the back. Abeni collapses forward in pain. ANGHARED262 begins to go towards RUNNING MOON who holds up one hand to the sky and the other to her. This makes her entire body freeze immediately. She cannot move, she cannot breathe. ANGHARED262, looks up at LEANING STRONG who disppears into the trunk of a tree.

Chilomé developed a spoken Earthroot language based on Swahili, Yoruba, Nahuatl, Southern Hood Dialect, Spanglish, Yaqui, and English that is entirely comprehensible to monolingual, English audiences. I followed up with the question, why these particular choices?

Chilomé: These are some indigenous roots I have witnessed in my time in Dallas and in Texas. If we are to imagine this place thousands of years in the future, I imagine the descendants of the fierce cultural workers of color in this city would be the ones to carry the work forward – particularly the black and brown folks at the margins. Of course, these are not all of the roots but some that intentionally include the Black diaspora… and then, of course, the indigenous mestizo community that has survived and reconstructed culture through layers of colonization alongside the black diaspora in the hoods of South Dallas, Oak Cliff, Pleasant Grove, etc. etc.

In their communications with each other, their Earthroot corporeal language also reflects the communal and ancestral values they honor. The poetics of the physical performance is captivating, as hand-gestures, salutations, interactions with advanced technology, and the morphing from male to female and back are all quite possible in this non-binary world. Since there is no choreographer credited, I asked about this salient feature of the performance in a subsequent email (lower case only punctuation is part of the original response).

Taylor: different elements of the movement were arrived at in different ways. There was no choreographer and most was created in collaboration with the collective.

…as writers, we had to consider the ways in which we would interact differently with organic technology, as decolonized bodies in a re-indigenized world. there are directions that the actors “interact” with the roots and trees as they “research” information in their interconnected web of knowledge (previously known as the internet) this laid the foundation for the movement in the world premiere where we found specific ways of navigating this web. we started the exploration by thinking of how we use screens now and the lead actors, with some amazing leadership from Ariana, worked together to find a common language and logic (how to retrieve a memory, pull up images, ask questions, etc.)

the gestural language that was used in the council of mothers scene was developed during the workshop production and was based on the idea of “voting” through gesture rather than speech. The technology could register the gestures in the space and give an immediate reading of the sentiments in the room and would allow for continued discussion amongst the community in times if discernment. we also wanted to imagine a people that honored corporeal expression and created a space where that expression could be shared in community. these were brought back into the space by ensemble members who had been in the workshop and then incorporated the contributions of newest members.

physical explorations would begin with a question around matriarchy, collective as three mixed race women of color who were at different places in our identity politics. Personally, I was moved to bring a lot of my cultural experiences as someone who identifies and a mestiza indigena and has been walking in some way or the other with actively political indigenous communities my whole life. I was born into a political family of campesinos that lived and continue to live the very real consequences of U.S. imposed colonial warfare in north and central america. I am also the daughter of spiritual activist mothers that are resilient leaders in our communities. The language and narrative I bring to the play reflects that.

Mercado Taylor has the last word:

Taylor: I think the Anghared character had a journey which was very similar to mine. Having grown up, the child of “immigrants ” in Los Angeles I was taught to assimilate and be as white as possible. I think the deep pain and anxiety that I felt was important in understanding her journey and her motivations. There have been so many beautiful, powerful, vulnerable black and brown women that have walked with me and helped me understand my place in this world as Indigenous Mestiza Colombiana. This work is dedicated to all of us out there, doing the work of healing – for ourselves, our families, our communities and our future.

Where Earth Meets the Sky leaves us, the audience, without answered questions. Rather, it invites us to consider our present choices with a clear eye towards the future. This includes vital environmental concerns as the health of our planet, its water, and the preservation of its plant and animal life. As such, this play reminds us of the interconnectedness of nature and our minuscule yet pivotal role in a complex and dynamic system.

The Company

Where Earth Meets the Sky is a collectively devised futuristic by three Dallas area women of color: Ariana Cook (plays Abeni, and did the properties), Edyka Chilomé (who also served as dramaturg), and Vanessa Mercado Taylor (also the director and scenic design collaborator with Christopher Taylor). Developed and produced by Cara Mía Theater Company, Dallas, Texas, David Lozano, executive artistic director, it premiered in April 2018 at the Latino Cultural Center, Dallas, TX.

Edyka Chilomé is a queer literary artist, performer, and cultural worker based in Dallas Texas.

Ariana Cook is the Managing Director of Cara Mía Theatre Co. as well as a mixed race actress, director, and playwright.

Vanessa Mercado-Taylor is an Indigenous Mestiza/Colombiana theatre director, producer, actor and educator who for more than a decade has made performances that create dialogues about human rights and social justice.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Teresa Marrero.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.