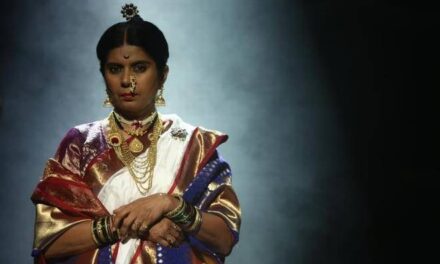

Last year Nina Király, dramaturg, theatre scholar, and regional editor for The Theatre Times passed away. With the republication of an interview made with her in 2014, we remember this outstanding theatre professional and world-renowned expert in Polish and Eastern European theatre, who worked with such luminaries as Tadeusz Kantor, Jerzy Jarocki, Anatoly Vasiliev, and others.

Zsolt Szász: You belong to the “war generation” which is commonly called the “great generation” in Hungary. In the history of Russia, the Great Patriotic War (1941–45) and the subsequent years were crucial. What pivotal experiences did you, as a child, have at that time?

Nina Király: During the war, I stayed in Smolensk with my grandparents. I have a vivid memory of the many soldiers who could be seen everywhere, of the burnt-out churches and the dead. And of the games we played, which were all related to burial. We found dead birds, buried them and carved crosses for them. And sometimes I can hear the sounds of that time as well. Actually, in theatre, too, it is the sounds that I am most sensitive to. I find intonation very important. When we returned to Moscow with my grandparents after the war – my parents had stayed there all through the war – we had difficult times, but I remember a lot of positive community experiences. And I had fantastic teachers, despite the fact that I attended an average district school only. For instance, our maths teacher at the elementary school was already teaching us Gauss; or although there were no foreign languages taught at that time, when the teacher realized that I had an ear for languages, she gave me private English lessons; or that our history teacher obsessively made us draw blank maps . . . This experience makes me say today that the operation of every state is determined by the quality of its intellectuals.

Zs. Szász: Your openness to languages and cultures may also be due to the fact that you, as a child, traveled widely in the country with your father, who worked as an engineer in the Soviet Army, spending more time at different places.

Nina Király’s father, Pyotr Petrovich Dubrovsky. Photography courtesy of the Király Foundation

Király: There are four languages that I can use at every level: Russian, Polish, Hungarian, and English. But I also went to a Lithuanian school, so I can still read, say, a Lithuanian fairy tale. And since I have been to the Caucasus, I am familiar with the Georgian alphabet. This kind of interest remained when I went to Lomonosov University in Moscow: I participated in ethnographic expeditions several times in the summer.

Zs. Szász: What was your major at university?

Király: Since I graduated from secondary school a year ahead of my peers, with a gold medal, I did not need to take an entrance exam for the university and was free to select from the courses. I needed permission to take two majors, and I chose English and Russian. I took Polish, too, because Western literature was published mainly in Polish translation at that time, especially after 1956. I made very many Polish friends this way, who ensured me a continuous supply of fresh literature. These contacts of mine have been kept alive. Since our accession to the EU these then-flourishing Slavic courses have unfortunately been cut back everywhere . . . But I was also into anthropology and began learning the Hungarian language at that time too – for love. But my teacher at that time was not my eventual husband, Gyula Király, but the inhabitants of Borzsa, a village in the district of Beregszász (Beregovo), where I spent two months and learned the basics. Thanks to Khrushchev’s ‘thaw,’ there were a lot of foreign students studying at the university at that time: English, Italians as well as Americans. One day in a park near Lomonosov University, I heard a group of foreigners speaking Russian, with someone – apparently, a literary scholar – among them talking about Dostoevsky. Well, that’s funny, I said to myself, what country can that be where they understand Dostoevsky even? That particular young man was Gyula Király. And shortly afterward, I decided to move to Hungary.

Zs. Szász: To change cultures is always very difficult. How did you take root in Hungary?

Király: I started out radically: translating a thousand-page novel by a nineteenth-century Hungarian novelist, József Eötvös (Magyarország 1514-ben / Hungary in 1514). Then I thought with my Hungarian artist friends that this would grow into a great cultural enterprise, but unfortunately, it did not. Nevertheless, I wrote 150 new words every day into my vocabulary notebook, half of which I forgot right away, but I did learn the other half. To answer your question in more concrete terms: I began teaching at Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) in 1965, first on a contract basis, then, from 1968 on, by appointment to the Slavonic Department, where my favorite course was the comparative analysis of Polish and Hungarian Romanticism. In 1973, when I defended my dissertation on Polish theatre, the independent Faculty of Polish Studies was created, which I am very proud of, because it granted Polish a prominent role among the other Slavic languages and literature.

Zs. Szász: When did you get close to theatre?

Király: I have always, since my childhood, been close to it. In Moscow, we used to go to the Bolshoi Theatre regularly, more to ballet and opera at first, because my dad had a very good singing voice. Later I also went to drama theatres regularly, where the best directors, such great masters as Tovstonogov, were working. And when I came to Hungary, as a doctoral student I chose the development of the Polish national theatre and the era of the Enlightenment and early Romanticism as topics for research, on which I worked for five years. I regularly went to Wrocław and Warsaw, where I became acquainted with theatre theoretician Jan Kott among others. In fact, we chose this topic together with him and my supervisor, Zbigniew Raszewski (the author of the famous Polish theatre historical monograph) in 1965, which was the 200th anniversary of Polish theatre.

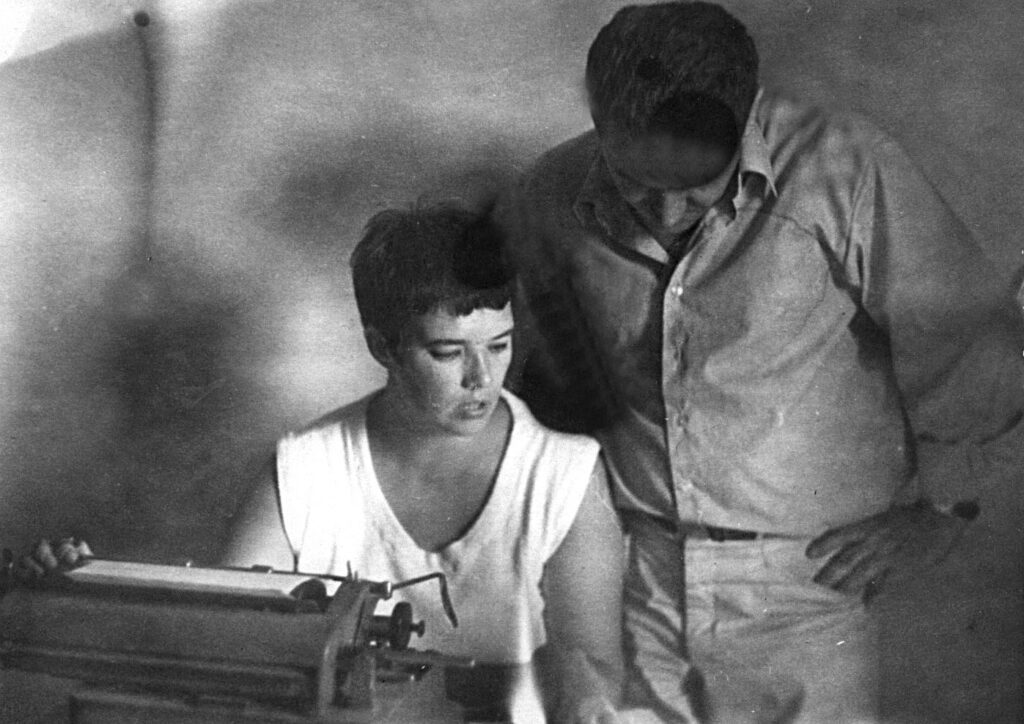

Nina Király with Gyula Király working at home. Photography courtesy of the Király Foundation

Zs. Szász: Jerzy Grotowski also worked in Wrocław at that time.

Király: Yes, it was the last era of his theatre in Wrocław, and I saw all the performances that I could see live in his Laboratory Theatre. It was a very intensive period in Poland up till 1968, with political scandals surrounding Mickiewicz’s Dziady(Forefathers’ Eve), with student riots and a lot of political events. However, few people know that Grotowski was very much tied to literary tradition, to Polish Romanticism, as he began with Słowacki’s Kordian; or that he was also fond of epic pieces; and that he had an awesome Hamlet-project, which never got realized but the idea was very nice, as his colleague, Flaszen, documented it. This was a most intensive and happy period for me, too.

Zs. Szász: 1975 saw the premiere of Tadeusz Kantor’s Dead Class in Krakow. How did you learn about it, and when did you meet Kantor in person?

Király: Happenings were in fashion in those years, so Kantor as an artist also directed such things. The first thing I saw by him was some happening in Warsaw. Later I learned about the ongoing rehearsals of Dead Class, and then I went to its opening as well. Yet it was not then that we met in person. When the acclaimed semiotician Yuri Lotman came to visit Budapest in 1984, we could already feel the upcoming significant changes. It even crossed my mind that I should return home, to Moscow. Lotman also kept saying what a pity it was that I did not stay there at the Institute of Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy, where I started work after graduation in the Department of Cultural History and where, besides Lotman, several famous semioticians were working, such as Boris Uspensky or Andrei Zalizniak. So I was at a loss as to what to do. And then I received a phone call from Krakow asking if I wanted to substitute for Professor Jan Mihalik at the Jagiellonian University to teach the course in the theatre history of Poland. So I took my children and left for Krakow. And on the day after my arrival, a colleague told me that Kantor was just beginning rehearsals for Let The Artists Die and asked me if I wanted to join him. And from that time on until his death I worked with Kantor.

Zs. Szász: You were also his colleague at Cricot 2.

Király: Yes. I participated in the symposia and helped with the preparation of the materials. That is why it was possible to have Hungary publish the first foreign-language translation of Kantor’s texts in book form (Halálszínház/Theatre of Death, Szeged, Prospero Könyvek, 1994). This volume is important not only from the perspective of theatre but also for the new kind of synthesis between fine art, music, and text. To me, who had been an expert in traditional theatre before, it meant that I needed to re-evaluate and reformulate all my knowledge and experience. By the way, Kantor was extremely sensitive and jealous of his actors and me, too, so we could only escape secretly to see a couple of performances at the Stary Teatr, for example. He was even difficult to persuade to use the gallery of the Stary for an exhibition, but it finally worked out somehow.

Cricot 2 Theatre’s sign in Krakow. Photography courtesy of the National Theatre Budapest

Zs. Szász: In retrospect, what is, in your opinion, the essence of Kantor’s reform of the language of theatre?

Király: He always used the texts of Gombrowicz and Witkacy (Witkiewicz) in his productions. However, he wrote the performance-text, the ‘scores’, on the basis of improvisations with the actors. Taking the Witkacy text as a starting point, the actors created a situation among themselves along the lines that Kantor had predetermined for them, so that what they were doing should not be make-believe or role play. Music came to be added to this created situation. Then they returned to the text.

It was no accident that Kantor gave the name Cricot 2 to his theatre. Because there had also been a Cricot 1 with mostly artists taking part and performing grotesque parodies of Romanticism. But even then it was already very important for Kantor that artists should control and transform their roles as actors. That artists should visualize their roles, ‘draw themselves into them,’ since they, as artists, have a lifetime’s experience of that, and in the meantime there is also a given text, the canvas to keep in mind. But, after all, they must have this whole thing performed, too. Anyhow, Polish theatre, not only in Kantor’s case, has typically had a way of distancing, with transpositions of this kind.

Kantor exhibition at MITEM 2016. Photography by Zsolt Eöri Szabó (http://www.eoriszabo.hu)

Zs. Szász: This feature can be noted with Wyspiański already. Returning to antique tragedies, he was both a reformer of the Polish dramatic language and the creator of the new, art nouveau visualization on stage. This tradition deriving from him has a profound effect on Polish theatre even to this day. The same is true of Kantor.

Király: Polish theatre is connected to mainstream European theatre through Wyspiański. Similar to the way Stanislavski used to connect to Craig at that time. An intricate context comes into being in this manner. But ever since I came to Hungary I have found that Hungarians tend to shut themselves off on account of their language, whereas these contacts and this openness are natural across the world. It was also typical of the art life of Berlin or Munich at the beginning of the twentieth century, with the ongoing cooperation of artists and theatre practitioners.

Zs. Szász: Do you think this sort of theatre-making proves sustainable after Kantor’s death?

Király: Jan Kott’s famous phrase might be quoted that after the death of Molière nobody is to sit in his armchair. Nobody is to sit in the chair of Kantor with impunity, either. But Kantor has a great impact on Polish theatre to this day. Take, for instance, the fact that Piotr Tomaszuk has used very many quotations by Kantor in his 2006 production of God Nijinski at the Teatr Wierszalin in Supraśl, in northeastern Poland. And Kantor’s last work, The Death of Tintagiles, with students from Milan, which was, on the one hand, a return to his own first stage direction, functions as a real message: it demonstrates that real, viable innovation can only be founded on tradition.

Zs. Szász: Between 1993 and 1999 you were the director of the Hungarian Theatre Institute and Museum (OSZMI). What concept did you have as head of this prestigious national institution? What are you most proud of concerning those five years?

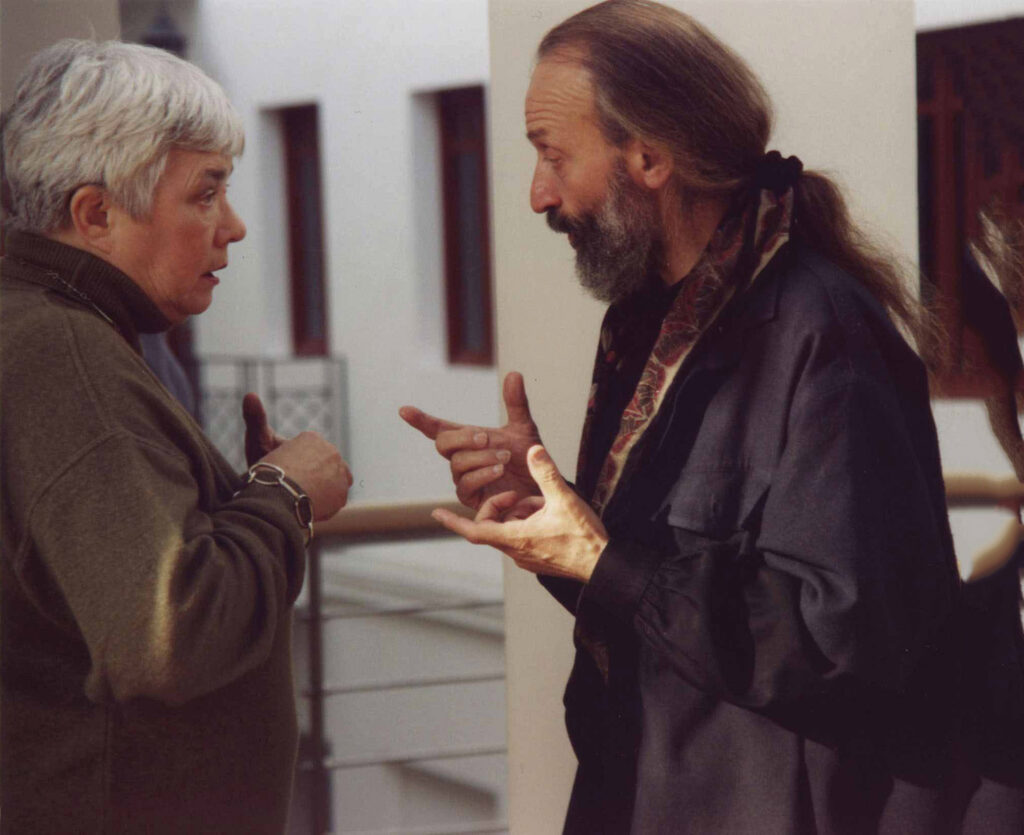

Király: My ambition was to place Hungarian acting in a wider European context and to attract as many European theatres into the country as possible. I also wanted foreigners to see more of us, Hungarians. I was delighted to have officially had the opportunity to nominate visual designers to the Prague Quadrennial, the most significant forum for scenographers. At first, it was not easy to persuade them to participate in the forum and to allow their works to appear in a publication, but we eventually managed, and even won a silver medal with it (Magyar színpadképírók/Hungarian Scenographers. Prágai Quadriennálé ’95, OSZMI, Budapest, 1995). As the head of the Hungarian Theatre Institute and Museum, I thought my most important task was to bring out in Hungarian translation as many foreign publications on theory, theatre history, and aesthetics as possible. Without this, it is impossible to think, to properly educate and train a new generation of creators or reviewers. Within the publishing program, the reorganization of the contents of our periodical Világszínház (World Theatre) was very important, with thematic issues coming out on anthropology, the avant-garde, and puppetry, for instance. The Kantor volume was followed by the publication of the writings of Anatoly Vasiliev and Jan Kott here. However, regrettably, I could not manage, during my term of office, to bring out, for instance, Eugenio Barba’s dictionary of theatre anthropology.

Nina Király at the book launch of Halálszínház (Theater of Death) at the Írók Boltja bookshop in Budapest in 1994. Photography courtesy of the Király Foundation

Zs. Szász: In 1999 you received a contract from artistic director Attila Vidnyánszky to work with him at the Csokonai Theatre in Debrecen, where you stayed until 2006. It must have been a bold undertaking in Debrecen to transform a regional repertory theatre into an experimental arts theatre.

Király: Attila Vidnyánszky’s appeal was that he turned to me to recommend foreign stage directors. Since theatre for me always begins with the stage director. I think that it is through the invitation of directors of outstanding originality that you can show something really new to the audience. Although people usually resist at first, later they say: “Well, let me see that again.” Initial reluctance is always reckoned on, and you do not have to worry about it. The audience should never be despised and humiliated by declaring that they don’t understand novelty. Some will leave the production but most of them will stay. When, for example, Vasiliev opened the A nagybácsi álma (The Uncle’s Dream) production in 1994 at the then Művész Színház, in Budapest, very many left, but then there were those who went to see it twice, and finally scenographer Igor Popov was awarded the Critics’ Prize that year. There is always a little resistance to novelty. At the same time, it will, sooner or later, challenge your imagination and curiosity. In Debrecen, I had to overcome my resistance to a rural town at first. Because, say, the distance between Madrid and Valladolid (which is home to a very important drama school at present) is the same, 200 km, and the train covers it in 45 minutes, whereas the train from Budapest to Debrecen takes two hours and a half to three hours to bump along. But the bigger risk was whether the actors and the audience would accept the famous directors I recommended. I feel that eventually, this did happen in the case of Andrzej Bubień or Victor Ryzhakov, for instance.

Nina Király with Anatoly Vasiliev in his theatre, School of Dramatic Arts, in Moscow. Photography courtesy of the Király Foundation

Zs. Szász: Let us consider a wider international terrain, too. It seems to me that in Western Europe, especially in German-language theatre, a kind of schematism has gained dominance in the formal expression of director’s theatre.

Király: I too find that the European theatre festivals were not so interesting recently. Perhaps it is because the great directors’ generation is growing old. And because the disintegration of the ensembles has begun in the eastern regions of the European Union, too, which was earlier a typical tendency in the West. It seems to me as if the relationship between tradition and innovation has become split. It is mostly in Russia that the relationship between, for example, masters and disciples or literary traditions and theatrical schools has remained steady. Students keep coming to Saint Petersburg or Moscow from republics that became independent after the disintegration of the Soviet Union to study drama. However, they are, at the same time, open to the Western world, Scandinavia or America as well. So there is greater movement and stronger globalization. But as I see it, there is nevertheless a slow return to theatre founded on stage directors of great originality.

Zs. Szász: Nationalist sentiment has inevitably strengthened, and ethnic traditions are coming to the fore again in Europe. In the former Soviet republics, for example, national theatres come into being one after the other, while they also remain tied to classical Russian theatrical schools.

Király: Already in 1991 Krystyna Meissner had begun the KONTAKT Festival in Toruń, Poland, where she invited productions from, for example, Siberia, but also from other republics of the former Soviet Union. At this festival, the national theme brought aesthetic novelties as well, which is due as much to the Russian school. In the meantime, in Yekaterinburg, the Russian traditions–based Nikolai Kolada School was founded, attracting playwrights, directors, and actors from regional Siberian towns, who then had great success in Moscow at the current Chekhov Festival, too.

Zs. Szász: I wonder if we, today, can expect the revival of theatre through some kind of synthesis between our own national tradition and the shared form language?

Király: Yes, it is an existing trend today. But beyond this, the media have a very important role to play now, with new media tools readily being used onstage by everyone. It can also be seen that theatres nowadays do not choose contemporary pieces of their own authors only, but, as we are to see from the Tatars at our current MITEM festival, they present works from other cultures, in this case, a Scandinavian piece (A Summer Day, by Jan Fosse). The director of the production, Farid Bikchantayev (the head director of the Galiaskar Kamal Tatar National Academic Theatre, in Kazan), was also brought up on the Russian school of psychological theatre, and this is such a unique connection, which makes this production most exciting. There is some kind of Scandinavian sadness in the production, the acting style is covert, yet it also has a deeper psychological approach, which the viewer finds unsettling: How can one, left to themselves, survive emotional ordeal? Where does love end? How do people become distant? The aesthetic novelty here lies in the visualization of the story, and it offers a fantastic experience throughout the performance.

Zs. Szász: There is an existing concept of cultural theory that predicts the focalization of current peripheries.

Király: Yes, and that is one reason why Asian theatres are so important. Take, for instance, the impact of Japanese theatre on Meyerhold, then on Kantor at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, it can be seen in the other direction, too: the 2013 Romeo And Juliet production at the National Theatre of China, in Beijing (directed by Tian Quinxin, a collaboration between the National Theater Company of Korea and the National Theatre of China) set during the time of the Cultural Revolution, is a real-world event. The Korean costumes, for example, a combination of Shakespearean style and native tradition, were beautiful, for which they received the Gold Medal at the Prague Quadrennial.

Nina Király. Photography by Anna Király

Zs. Szász: Does this re-discovery of Asian culture indicate a kind of return to the art philosophical ideas of Art Nouveau a hundred years ago? The period when philosophy and sacrality were embodied in a new kind of sensitivity and created new artistic forms?

Király: Yes. A new kind of aesthetic approach, open-mindedness and, in addition, a deeper immersion are typical of the present creators. And the wisdom that we understand our culture better through the other’s.

Zs. Szász: Were these also the main selection criteria for the shows at MITEM?

Király: The initial selection criterion for our festival was that it should be the meeting of national theatres. But the Warsaw theatre had already created such a festival. So I thought we had better build the concept of the festival on stage directors. That is why Russian theatre became the guest of honor at the festival. And similar to the first KONTAKT Festival, I wanted to present, first of all, those new national theatres which grew out of the Russian school but which have their own special style of acting, visuality, and musicality. Almost each shortlisted country has a favorite author: for example, it is Shakespeare for the Georgians, Molière for the Bulgarians, but their director, Morfov, once had a fantastic Peer Gynt, too. Rimas Tuminas is the most brilliant interpreter of Romantic pieces, mixed with some surrealism characteristic of Lithuanians. In addition to the detectable impact of the Russian school in his work, each of his productions is characterized by a projection of the play onto the ethics, mentality, and imagination that Lithuanians own.

Zs. Szász: With next year’s festival already in mind, where should we orient ourselves? Are we in a position here, on the border of East and West, to unite these two worlds in some way?

Király: I thought we would go a little further south next year, orienting towards Romanian, Spanish, Italian and French theatres as well. Spanish theatre is also going through an era of renewal; contemporary Spanish dramas are very exciting, too, mainly those by authors of the generation in its forties today. But Serbian and Croatian theatres could also be better presented, as a lot of interesting productions were made there. Although they have fewer great director’s theatres, the actors are excellent. And let us not forget about Northern Africans, either . . .

—This interview was conducted in Budapest in March 2014.

Nina Király. Photography by Nikita Gontarczyk

Nina Király (née Nina Petrovna Dubrovskaya, (1940 – 2018) was a theatre historian, dramaturg, lecturer and festival curator, and an internationally renowned expert of Eastern European theatre. Born in Moscow in 1940, she graduated from Lomonosov University (today: Moscow State University) in 1962 from the Russian Philology Department (Linguistics and Anthropology). That same year she conducted research at the Slavic Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Department of Cultural History). Those years laid the foundation for her studies in the area of Theory of Culture and Communications in the Department of Cultural Semiotics (under the guidance of Yuri Lotman, Vyacheslav Ivanov and Boris Uspensky). In 1964 she moved to Budapest, Hungary, with her husband, the literary historian Gyula Király.

From 1965 she worked as an assistant lecturer, and from 1973 as an associate professor in the Eötvös Loránd University’s (ELTE) Slavic Department, until 1994. From 1984 till 1990 she worked as a guest lecturer at the Jagello University in Krakow, Poland (Department of History and Theory of Theatre), where she taught the theory of world theatre and the history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Polish theatre. During this period she became Tadeusz Kantor’s official collaborator at his Cricot 2 theatre. She also collaborated with other famous Polish directors such as Jerzy Jarocki, Włodzimierz Staniewski and Andrzej Wajda.

From 1993 to 1999 Király served as Director of the Hungarian Theatre Institute and Museum (OSZMI). During this period she initiated, edited and brought to publication many books by and about famous international theatre directors and creators, introducing them to Hungarian readers for the very first time. She edited a compilation of the essays and manifestos of Tadeusz Kantor in Hungarian translation (Halálszínház, Prospero Könyvek, Szeged, 1994), the essays of Jan Kott (A lehetetlen színház vége, OSZMI, Budapest, 1997), and the theoretical writings and rehearsal notes of Anatoly Vasiliev (Színházi fúga, Budapest, OSZMI, 1998). The catalog she co-edited about Hungarian set and costume designers (Magyar színpadképírók, Prágai Quadriennálé ’95, OSZMI, Budapest, 1995) won a silver medal at the 1995 Prague Quadriennal. Nina Király strived to bring international directors and scenic artists to the theatre and to share their work with the Hungarian public. She also helped take important Hungarian productions to audiences around Europe. She served on many festival jury panels across Europe.

Between 1999 and 2003 she worked as a freelance theatre researcher, critic and artistic advisor for the International Divadelna Nitra Festival (Slovakia) and for KONTAKT (Poland). She also held seminars at Anatoly Vasiliev’s Dramatic Art School theatre in Moscow.

Between 2003 and 2004 she was advisor for international theatres at the Új Színház (Budapest). She also worked as the editorial member of Société Internationale d’Histoire Comparée du Theâtre, de l’Opéra et du Ballett (Université de Paris IV – Sorbonne); was a member of the advisory board for Theater (Yale School of Drama / Yale Repertory Theatre, USA); and worked as co-editor of the Polish theatre periodical Pamietnik Teatralny.

During the period 2006–2013 Nina Király was the artistic consultant for international projects at the Csokonai Theatre in Debrecen. From 2013 till her death she worked as the Head of the International Department at the National Theatre, Budapest. From 2016 to 2018 she also worked as a regional editor (Hungary) of TheTheatreTimes.com.

For her services to theatre, Nina Király was the recipient of several awards, including L’Ordre du Merite Culturel (Ministry of Culture, Poland, 1975), the Jászai Mari Award (Hungarian Ministry of Culture, 2012) and the Witkacy Award (International Theatre Institute [ITI], Poland, 2015).

Zsolt Szász is editor-in-chief of the art journal of the National Theatre in Budapest, Szcenárium. He began his career as an artist, attending the respective art schools Medgyessy Ferenc, in Debrecen, and Dési Huber István, in Budapest, as well as studying geography and drawing at the Teacher Training College in Nyíregyháza. His theatre career began in 1978 at the Vojtina Puppet Theatre. In cooperation with puppet dramaturg Márta Tömöry, he created the annual International Nativity Play Meeting in 1990 to present the sacred-dramatic tradition of the Carpathian Basin. From 1993 to 2012 he was the artistic director of the International Winged Dragon Street Theatre Festival in Nyírbátor. Zsolt Szász is the recipient of numerous awards as an actor, puppeteer and director with theatrical formations established by himself (Proli-Hystrió, MéG Theatre, Hattyúdal Theatre). In 2007, he won the Blattner Award for his work as a puppeteer. His productions as a director include Talizmán (2008) and Csongor és Tünde (2010), both at the Csokonai Theatre in Debrecen. As a dramaturg at the National Theatre in Budapest, Zsolt Szász worked in Vitéz lélek (2013), János vitéz (2014), Csíksomlyói passió (2017), Bánk bán (2017) and Egri csillagok (2018). His papers appear regularly in the theoretical journal of the Hungarian Academy of Arts, Magyar Művészet.

This is a shortened and revised English version of an interview that was first published in Hungarian in Szcenárium (II. 2014/3), the magazine of the National Theatre, Budapest. https://nemzetiszinhaz.hu/hirek/2014/03/szinhaz-es-emlekezet

English translation by: Mrs Durkó, Nóra Varga.

This version for the TheatreTimes.com was edited by Katalin Trencsényi.

The editors express their gratitude to the National Theatre, Budapest, and to Anna Király and the Király Foundation (https://www.kiralyfoundation.hu/kiraly-nina) for their help with this article.

Every effort has been made to find the copyright owners of the photographs used and gain their permission for using their work with this article. If you have more information on this, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us at: k.trencsenyi@thetheatretimes.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zsolt Szász.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.