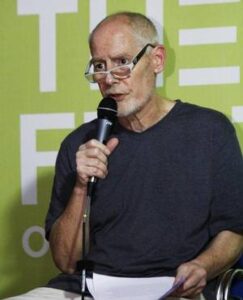

Phillip Zarrilli. Photo Credit: KK Najeeb.

The actor-director was at the 12th International Theatre Festival of Kerala (ITFoK) in Thrissur with his play, Told by the Wind. Despite a hectic schedule, Phillip managed to take time out to discuss his work and interculturality.

Excerpts from an interview…

Renu Ramanath: Interculturality has been central to your work and training process. So, what does ‘intercultural’ mean to you?

Phillip Zarrilli: To me, life is a process of encounters and negotiations. You encounter something, you respond and negotiate. It’s so unless you’re somebody with a closed mindset, where you wrap yourself within a specific way of thinking, putting yourself in a box, whether about ideas, people, other religions or other cultures. I think it’s much more interesting when we encounter and try to negotiate. So, interculturalism is not just about ‘between cultures’. It is a way of seeing the world. The question is whether someone is open to a real, face-to-face encounter with others. I think, unfortunately, the world we live in is much more a world of separation than what it was when I was younger.

R.R: Do you think interculturality has relevance in the contemporary world?

P.Z: Sure. Because it’s about encounter and understanding, and wanting to embrace difference. And not just, you know, be in a box, so as to speak. Unfortunately, I think, a lot of politicians are creating boxes and pitting one box against another. In the acting studio, the problem with the term interculturalism is that when it was used for the first time, it was limited to the early works that Peter Brook and the other kind of directors were doing when they brought together people from different cultures. I’d call that surface interculturalism. But, it’s a different kind of situation for those who work in the acting studio, doing it for years on end. There’s a give and take that takes place in a studio. When I first came to Kerala and studied Kathakali in 1976, my teacher MP Sankaran Namboothiri (MPS) was generous with his time. Both MPS and Killimangalam Vasudevan Namboothirippad, the then superintendent of Kerala Kalamandalam, were people who liked to think. Likewise, my Kalaripayattu teacher Govindankutty Nair was also generous with his time. The encounters that took place between all of us, in and outside the studio, the discussions, the exchanges of ideas about body, thought and reflection, that willingness to open up, were intercultural. I have brought together Kalarippayattu and Tai Chi into my practice. For me, this process of negotiation is taking place within my body and through the body-minds of those who were training in the studio with me. Contemporary theatre in Kerala, or in India itself, came about via an encounter with the West. So, it is intercultural on one hand, and still growing with its own rootedness in India.

R.R: You recently co-edited a book, Intercultural Acting and Performer Training, with T Sasitharan, Director, Intercultural Theatre Institute, Singapore, and Anuradha Kapur, former Director, National School of Drama. Was that book an attempt to define ‘interculturalism?’

P.Z: Rather than ‘defining,’ it was an attempt to open up. My book, Psycho Physical Acting: An Intercultural Approach After Stanislavski, published in 2009, is about my training process. But the purpose of this present book, Intercultural Acting and Performer Training, was to give space to other voices. There are 14 chapters written by different people, about different dimensions of interculturalism as it exists today. We, the three editors, did not even write a joint introduction. The book has a three-part introduction.

R.R: Is there interculturalism, however subtle, in your directorial works?

P.Z: Told by the Wind is an intercultural performance, inspired by the Japanese art form, Noh. However, it looks nothing like Noh. Only the dramaturgy and our performance are inspired by principles of Noh. I’d call it a subtle form of interculturalism. However, when we performed it in Japan, the Japanese audience who knew Butoh and Noh appreciated it. They could see the subtle elements, the influences.

The 2015 production Playing the Maids, which we did with Korean, Irish and Singaporean Chinese collaborators, was another subtle form of interculturalism. The text was primarily in English, but it had Mandarin, Korean and Irish Gaelic. The Singaporean performer had worked with Wayang Wong, the Javanese classical dance theatre, and her movements were subtly infused with the form. One of the Korean dancers showcased her roots in classical Korean dance.

R.R: You have worked with differently-abled actors in some of your works.

P.Z. I’ve done two plays with differently- actors. One was The 8 Fridas, which Kaite O’Reilly had written. She has been working with differently-abled artists. Richard III Redux or Sara Beer (Is/Not) Richard III, co-created by me and Kaite, was written for Sara Beer, a Welsh actress who had scoliosis. It was written as a response to the vilification of Richard III, as the epitome of evil because he had a disability. When I am working with differently-abled artists, I have to adapt my teaching to their individual needs, not just to a general group of actors.

This article was originally posted at thehindu.com on January 23, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Renu Ramanath.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.